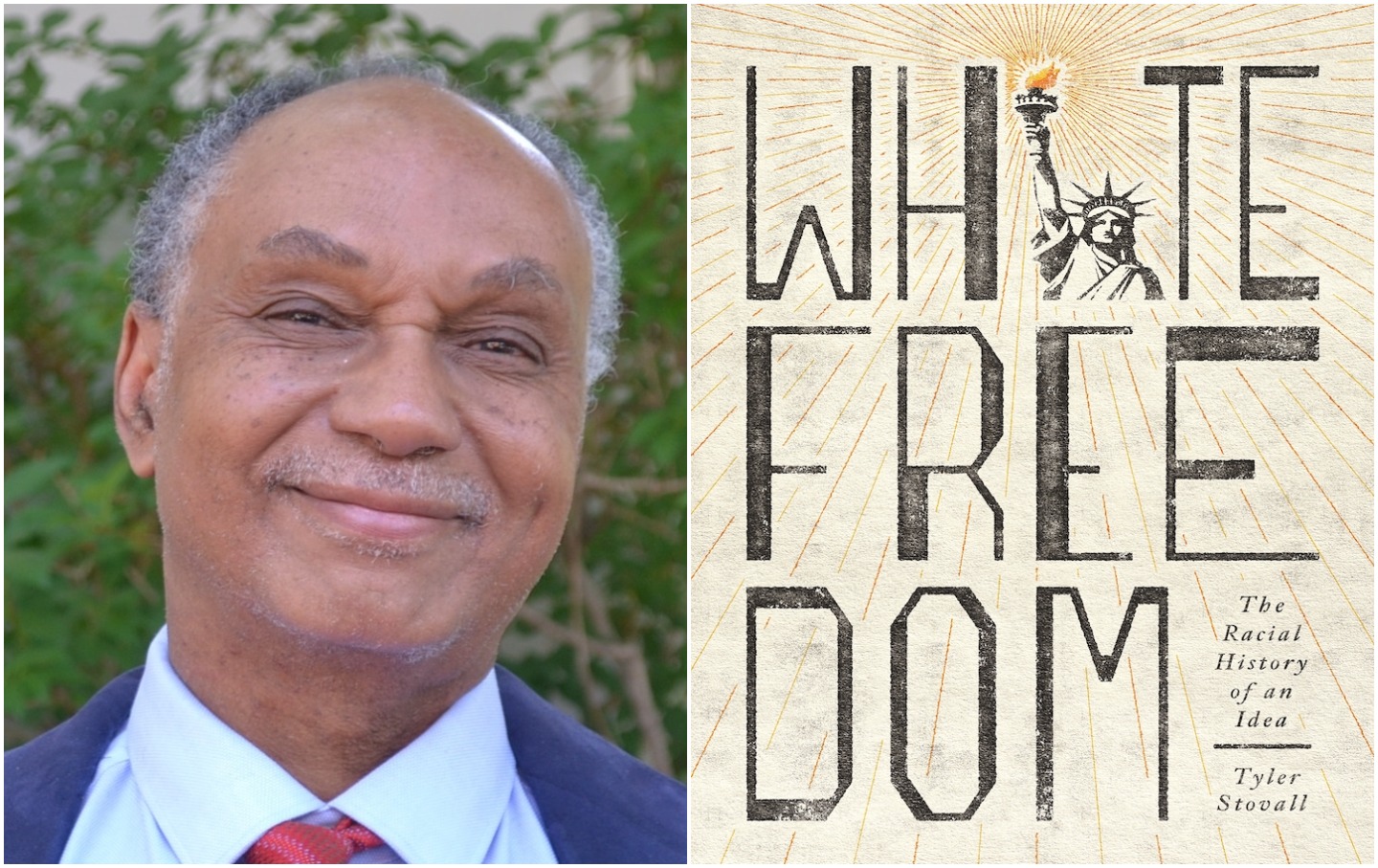

Tyler Stovall.(Courtesy of the author)

In his new book, White Freedom: The Racial History of an Idea, the historian Tyler Stovall seeks to offer a new approach to the relationship between freedom and race in modern Western societies. This approach reveals a different historical perspective for understanding how the Enlightenment era, which provided the basis for modern Western conceptions of human freedom, coincided with the height of the transatlantic slave trade, and for how the United States could be founded simultaneously upon ideas of both liberty and African slavery, Native American genocide and systematic racial exclusion.

Stovall does so by arguing for an alternative explanation to what he describes as the standard “paradoxical” interpretation of freedom and race. “If liberty represents the acme of Western civilization,” says Stovall, “racism—embodied above all by horrible histories like the slave trade and the Holocaust—is its nadir.” In other words, the paradoxical approach sees freedom and race as opposites. This means that there is nothing about freedom that is inherently racialized. The relationship between freedom and race from this perspective, argues Stovall, is due more to “human inconsistencies and frailties than to any underlying logics.”

Stovall challenges the paradoxical view by arguing that there is no contradiction between freedom and race. Instead, he thinks that ideas of freedom in the modern world have been racialized, and that whiteness and white racial identity are intrinsic to the history of modern liberty. Hence Stovall’s notion of white freedom.

Stovall’s book aims to tell the history of white freedom from the French and American revolutions to the present. But to what extent can the vast history of modern freedom be reduced to white freedom? How can white freedom account for class differences? Moreover, if modern freedom is racialized how is it to be differentiated from fascism and others forms of white nationalism? And can political freedom break away from the legacy of white freedom? To answer these questions, I spoke with Stovall about the history of US slavery and immigration, the fascism of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, Trumpism, and Joe Biden’s recent election to the White House.

—Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins

Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins: Can you explain your concept of white freedom?

Tyler Stovall: In this study I argue that white freedom, which is a concept of freedom conceived and defined in racial terms, underlies and reflects both white identity and white supremacy: To be free is to be white, and to be white is to be free.

DSJ: Your thinking on white freedom has been strongly influenced by whiteness studies. Can you explain the connection between the two?

TS: Whiteness studies starts from the proposition that whiteness is not simply the neutral, unexamined gold standard of human existence, arguing instead that white identity is racial, and white people are every bit as much racialized beings as are people of color. White Freedom explores the ways in which the ideal of freedom is a crucial component of white identity in the modern world, that great movements for liberty like the American and French revolutions or the world wars of the 20th century have constructed freedom as white. More generally, this book follows the tradition of whiteness studies in considering how an ideology traditionally viewed as universal in fact contains an important racial dimension. I argue that frequently, although by no means always, in modern history, freedom and whiteness have gone together, and the ideal of freedom has functioned to deny the realities of race and racism.

DSJ: How might you respond to the criticism that your notion of white freedom is potentially monolithic? How do you account for its diverse historical application and impact, especially concerning class differences?

TS: I would begin by saying that white freedom is by no means the only kind of freedom, that in modern history other, more inclusive visions of liberty have frequently opposed it, and those visions have often interacted and mutually reinforced each other. One thinks, for example, of the rise of the movements for women’s suffrage in 19th-century Britain and America out of the struggles to abolish slavery. The concept of white freedom does position race at the center of the history of liberty, something I found it necessary to do both because it has frequently been left out or seen as peripheral to the story, and because making it more central in my view offers new insights about the nature of freedom in general.

Class differences, and the ways in which they have historically been racialized, play an important role in the development of white freedom, as well. The example of Irish immigrants during the 19th century provides an interesting case in point. In both Britain and America, Irish immigrants not only occupied the lowest rungs of society but were frequently racialized as savage and nonwhite during the early parts of the century. In Britain, integration into working class movements like Chartism and the 1889 London dock strike to a certain extent brought them white status, whereas in America the ability of the working-class Irish to differentiate themselves, often violently, from African Americans gradually helped enable their acceptance as white by the dominant society, integrating them into American whiteness.

DSJ: You argue that the paradox of American slaveholders fighting for liberty is not a paradox at all if one considers the racial dimensions of the American idea of freedom during the American Revolution. Denying freedom to Black slaves was not a contradiction, you show, because freedom was reserved for whites. How does your thinking about white freedom and slavery differ here from the notable The New York Times’ 1619 Project, which caused a storm of controversy by arguing that the American Revolution was primarily waged to preserve slavery?

TS: I think the 1619 Project’s argument that the founding fathers waged the American Revolution in defense of slavery has much to recommend it, although I think this debate could benefit from some nuance. Certainly American slaveowners, who were amply represented among the proponents of independence, worried about the implications of the 1772 Somerset case, which banned slavery in Britain, for the colonies and their own property. The 1775 call by Lord Dunmore, royal governor Virginia, to American slaves to free their masters and fight for the British further outraged them, leading them to condemn him in the Declaration of Independence for having fostered domestic insurrections against the colonists. It is also true that this question bitterly divided Northern and Southern patriots, in ways that ultimately prefigured the Civil War. It is quite possible that revolution devoted to abolishing slavery, as many Northerners wanted, would have failed to enlist the support of Virginia and other Southern colonies and thus would have gone down to defeat. Whether or not that means that the Revolution’s primary goal was the preservation of slavery was less clear.

However, there are other ways to approach this issue, which the current debate has tended to neglect. First, one must consider the perspective, and the actions, of the slaves themselves, who constituted roughly 20 percent of the population of colonial America. White Freedom not only considers the question of slavery central to the American Revolution but also sees the Revolution as one of the great periods of slave resistance and revolt in American history. Tens of thousands of slaves, including 17 belonging to George Washington himself, fled their plantations in an attempt to reach the British lines and freedom. Whether or not white patriots believed they were fighting for independence to preserve slavery, many of their slaves certainly did, and acted on that belief with their feet. American history to this day praises Blacks like Crispus Attucks who fought for the Revolution, but ignores the much larger number of American slaves who took up arms for the British. For many African Americans, therefore, the American Revolution was certainly a struggle for freedom, but for freedom from their white American owners and the new independent nation they fought for.

Second, one should underscore the basic point that, whatever the relative motivations of the patriots of 1776 in seeking freedom and independence from Britain, the new United States of America they created was a slave republic, and would remain so for the better part of a century. It is certainly true that the Revolution resulted in the abolition of slavery throughout the North after the Revolution, but that did not change the fact that the overwhelming majority of African Americans were slaves before 1776 and remained so for decades thereafter. Moreover, far from a relic of an imperial past, slavery proved to be a dynamic and central part of America’s economy and society during the early 19th century. Whether or not American patriots revolted to preserve slavery, the success of their revolt did exactly that, creating a new nation that largely reserved freedom for whites.

DSJ: The Statue of Liberty might be considered the most well-known symbol of freedom in the modern world. You provocatively state that “it is the world’s greatest representation of white freedom.” Why is this the case?

TS: The Statue of Liberty symbolizes white freedom in several respects. In my book I analyze how both its French origins and its establishment in America underscore that perspective, and in doing so illustrate the history of white freedom in both nations. In France the image of the statue drew upon the tradition of Marianne, or the female revolutionary, most famously depicted in Eugène Delacroix’s great painting Liberty Leading the People. Yet at the same time it represented a domesticated, nonrevolutionary vision of that tradition; whereas Delacroix’s Marianne is carrying a rifle and leading a revolutionary army, the Statue of Liberty stands demurely and without moving, holding a torch of illumination rather than a flame of revolution. She is the image of the white woman on a pedestal. The racial implications of this domestication of liberty became much clearer in the United States: Although France gave the statue to America to commemorate the abolition of slavery in the United States, Americans soon ignored that perspective and instead turned the statue into a symbol of white immigration. The broken chains at Liberty’s feet that symbolized the freed slave were effectively obscured by the pedestal and more generally by the racial imagery surrounding the statue, and remain so to this day. America’s greatest monument to freedom thus turned its back on America’s greatest freedom struggle, because that struggle was not white.

Moreover, many Americans In the early 20th century considered the statue an anti-immigrant symbol, the “white goddess” guarding America’s gates against the dirty and racially suspect hordes from Europe. Only when the immigrants, and more particularly their Americanized descendants, were viewed and accepted as white did the Statue of Liberty embrace them. To this day, therefore, America’s greatest monument to freedom represents above all the history of white immigration. No equivalent memorials exist on San Francisco’s Angel Island to commemorate Chinese immigration, or on the US-Mexican border to memorialize those Americans whose ancestors came from Latin America. The Statue of Liberty effectively conceals the fact that New York City was itself a great slave port, so that for many the arrival in the harbor represented bondage, not liberty. Not only the statue’s white features, but its racial history, make it for me the world’s greatest symbol of white freedom.

DSJ: One implication of your argument about white freedom is that it suggests that the modern history of liberal thought actually shares something in common with the fascism of Hitler and Mussolini, namely that both systems of government defined freedom in racial terms. What, then, fundamentally distinguishes these understandings of freedom?

Get unlimited access: $9.50 for six months.

TS: As I and many other historians have argued, there are some fundamental similarities between fascism and liberal democracy when it comes to race. In some ways, the increasing emphasis on the role of the state as the central locus and guarantor of freedom found its logical culmination in the fascist state, which rejected individual liberty, instead defining freedom as integration into the racial state. But I would also point out two important differences. First, Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany stated their commitment to a racist vision of freedom far more explicitly and dramatically than did the democracies of the liberal West. The Nazi vision of a racial hierarchy in Europe with Aryans had none of the pretensions of uplift and stewardship found in Western imperialism, but instead called for domination and ultimately genocide. The horrors of the Shoah were a foretaste of what awaited Europe, especially Eastern Europe, had Nazi Germany triumphed. The liberal democracies of the West, for all their racism, did not share that vision, were instead horrified by it, and in the end combined to destroy it.

Following from this point, I would also argue that, unlike liberal democracy, European fascism developed in a climate of total war, which fundamentally shaped its vision of race and freedom. Fascism and Nazism were born at the tail end of World War I (both Hitler and Mussolini were war veterans), and their histories culminated with World War II. The era of total war powerfully reinforced state racism—the idea that the enemy posed a biological threat to the nation. This happened in the West as well, of course, but did not constitute the heart of national identity in the same way. Moreover, unlike in fascist Europe, total war in the West also created a massive movement against white freedom, for a universal vision of liberty.

DSJ: I found your parts of the book on the end of the Cold War fascinating. Regarding Eastern Europe, you write, “The overthrow of communist regimes in this period happened in the whitest, most ‘European’ part of the world, one barely touched by the history of European overseas colonialism or non-European immigration.” Does this view of Eastern Europe fall prey to a mythology of white homogeneity, which is exploited by white nationalist leaders in Eastern Europe today driven by anti-immigrant and Islamophobic sentiment? The region had long had millions of immigrants from Central Asia.

TS: There are very few, if any, purely “white” parts of the world, and Eastern Europe’s contacts with Asia go back at least to the Roman Empire. There is, for example, an interesting history of Blacks in the Soviet Union, which was itself a regime that spanned and brought together Europe and Asia. I would nonetheless argue that, compared to the rest of the continent and to the Americas, the peoples’ republics of Eastern Europe lacked racial diversity, a situation that led many American conservatives to embrace their resistance to the Soviets during the Cold War as a struggle for white freedom. In the minds of many, the liberation of Eastern Europe from Soviet control represented a continuation of the war against Nazi rule of Western Europe, an unfinished campaign to ensure freedom for all white people. It was counterintuitive to witness nations of white people as “captive” or “enslaved,” so that the Cold War against Soviet Communism had an important racial dimension. The collapse of the Soviet bloc represented in theory the unification of white Europe, yet at the same time it underscored the fact that Europe wasn’t really “white.” The dramatic rise of ethnic and racial tensions in the former communist countries, especially eastern Germany, after 1991 illustrated the extent to which the victory of whiteness was not completely assured in the post-Soviet era.

DSJ: Do you understand Trumpism to be a white freedom backlash to the Obama administration or in continuation with the longer history of white freedom? Intellectuals and pundits, for example, are significantly divided on the question of whether Trumpism is unleashing long-standing fascist impulses in this country, especially given the events of January 6. Where do you stand?

TS: The Trump phenomenon certainly represents a backlash against the Obama presidency, but it goes well beyond that. In my book I discuss how the campaign for universal freedom represented by the campaign civil rights and many other popular movements provoked the rise of the New Right, which in many ways reinforced America’s history of white freedom. The current Freedom Caucus of the House of Representatives, composed overwhelmingly of white conservatives, exemplifies that. To an important extent, Trumpism represents a continuation of that political movement which triumphed under Ronald Reagan. At the same time, however, the Trump presidency, in contrast with Reaganism, has sounded a defensive and at times even desperate note, a fear for the survival of white freedom. The election of Barack Obama demonstrated that a universal vision of liberty could triumph at the highest levels of American society and politics, prompting an anguished reaction that created the Tea Party and other reactionary movements. The fact that Trump never won a majority of the popular vote combined with the increasingly multicultural and multiracial makeup of America’s population has led many to believe that the days of white freedom are in fact numbered. The fact that so many Americans cling to Donald Trump and his Republican party, in spite of their outrageous and buffoonish behavior, I believe arises out of this elemental fear.

I do believe events in America since the 2020 presidential election show that Trumpism has the potential to morph into an outright fascist movement. We have never in the modern era witnessed such an outright attempt to overthrow the will of the electorate after an American election, one grounded squarely in the fascist technique of the Big Lie. It has represented the culmination of Republican party efforts to suppress the ability of peoples of color to vote, efforts whose history goes back to the white terrorist campaign against Reconstruction after the Civil War. Moreover, I believe that if fascism does come to America, it will come in the guise of white freedom. The insurrection of January 6 is a case in point. On that day America witnessed the spectacle of thousands of mostly white demonstrators invading the US Capitol Building and trying to overthrow the government. They proclaimed their movement as a campaign to protect their freedoms, and were for the most part allowed to depart peacefully after violently invading federal property. If that didn’t demonstrate that whiteness remains an important part of freedom in America, I don’t know what does.

DSJ: Given mainstream acceptance of Black Lives Matter and Biden’s election to the White House, what do you see the implications to be for white freedom today in this country?

TS: For me and many other African Americans, one of the most surprising things about the murder of George Floyd was the intense reaction by so many white people against the official brutalization of Blacks in America. Leaving aside the rather belated nature of this reaction, or the observation that a movement calling for the right of African Americans not to be murdered is hardly radical, the mainstream acceptance of Black Lives Matter does point to a new day in American racial politics, a new affirmation of universal freedom.

Joseph Biden’s electoral victory, and his acknowledgment of his debt to Black voters and voters of color, also suggests the limits of white freedom in American politics. The fact remains, however, that 74 million Americans voted to reelect Donald Trump. He continues to dominate the base of the Republican Party and maintains a wide base of support in the nation as whole. White freedom is in many ways on the defensive, but that can make it more dangerous than ever. It also remains to be seen how committed President Biden is to a progressive vision of liberty. Initial signs seem encouraging, but during the election campaign he boasted of his ability to work across the aisles with white Southern senators to resist busing for school integration. Such bipartisanship in the past led to Jim Crow and Black bodies swinging from trees. Hopefully President Biden will prove more adept at resisting the Republicans’ siren song of white freedom.

DSJ: Finally, very little is mentioned in White Freedom about the political tradition of democratic socialism, which is experiencing a revival today. Do you believe it is a viable option for resisting white freedom today?

TS: I think democratic socialism is not only viable but vital in the struggle against white freedom. The fact that a significant segment of the white working class has embraced Trumpism is by no means inevitable, but rather speaks to the widespread conviction that the Democratic establishment has abandoned the concerns of working people. Some people who voted for Donald Trump in 2016 also supported Bernie Sanders, for example. Right now in America one of the strongest reasons for the survival of white freedom is the belief of many white workers that their racial identity “trumps” their class position, that, in a political world where no one stands up for working people and their interests, racial privilege is their greatest asset. The election to the presidency of a key member of the Democratic establishment like Joseph Biden does not augur well in the short term for changing this perspective, yet as the painstaking work of Stacey Abrams in Georgia has demonstrated there is no substitute for long-term political organizing. Socialism does have the potential to empower all people and thus demonstrate the universal nature of liberty. Developing and actualizing that potential will be a central part in the campaign to render white freedom history.

Daniel Steinmetz-JenkinsTwitterDaniel Steinmetz-Jenkins runs a regular interview series with The Nation. He is an assistant professor in the College of Social Studies at Wesleyan University and is writing a book for Yale University Press titled Impossible Peace, Improbable War: Raymond Aron and World Order. He is currently a Moynihan Public Scholars Fellow at City College.