The First Great Novel About Virtual Reality?

Colin Winnette’s disorienting Users examines the limits of morality and imagination as they exist online and in video games.

Colin Winnette’s fifth novel, Users, opens with its protagonist, a virtual-reality game designer named Miles, opening a death threat he just got in the mail. He resolves not to worry about it, throws it away, and then swiftly panics and digs it out of the trash in case he needs it as evidence later. In bed that night, he lies awake, tormented not by the thought of a violent death but by the phantom smell of some old rice in his trash can—and not just the rice, but “the cubes of lamb that had nested on the rice maybe two weeks prior.” It is evident that Miles is displacing his anxiety onto his fear that the smell remains; it is also evident that he has an overactive imagination, one that, as the novel goes on, reveals itself to be both the source of his livelihood and the bedrock of his uncertain, dread-filled daily life. We all live, to a certain extent, in an age in which technology and imagination are intertwined, a limited and limiting arrangement for anyone. For Miles, whose job renders the two inextricable, it represents inexorable ruin.

Books in review

Users

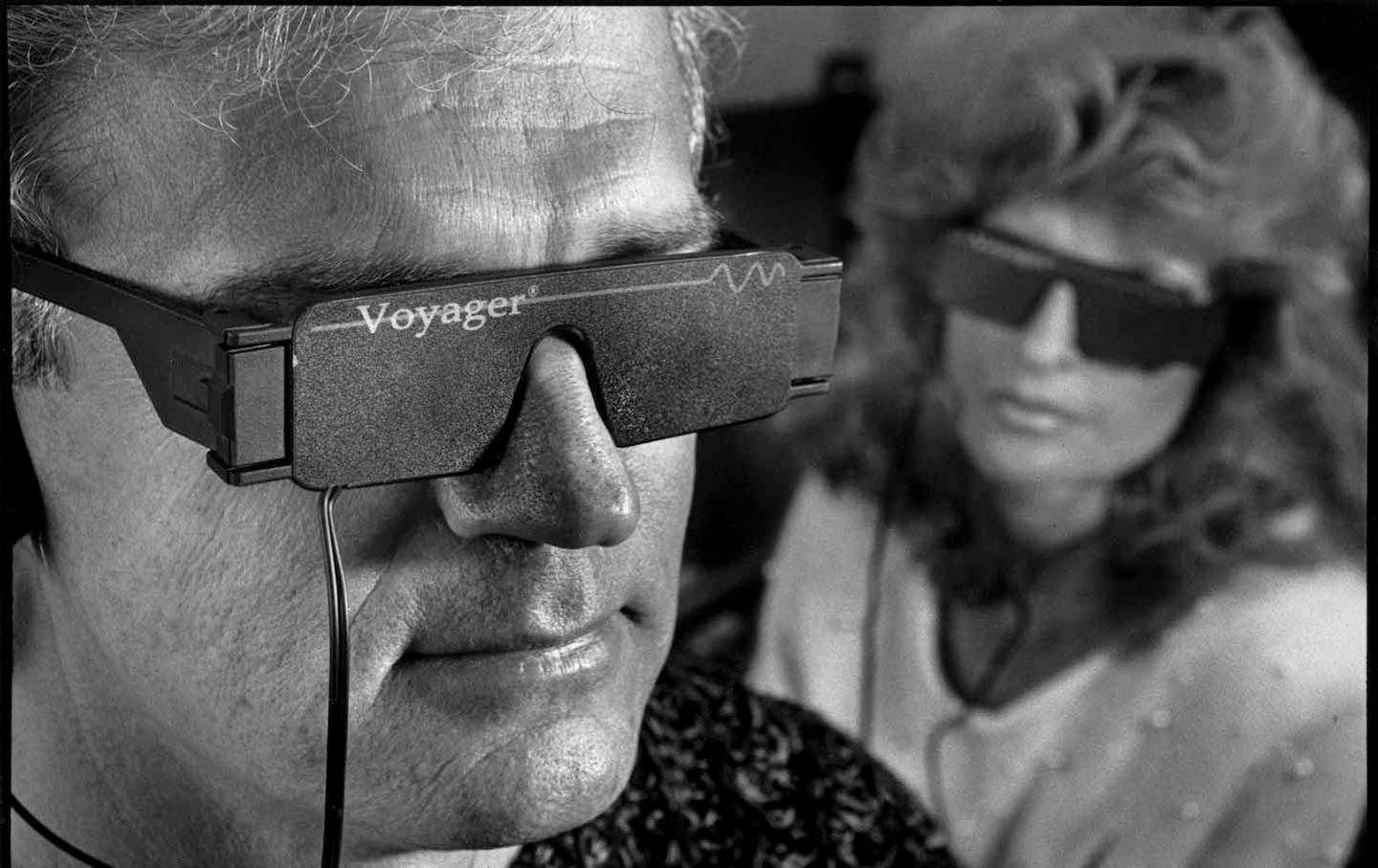

Buy this bookUsers seems, initially, like a run-of-the-mill tech satire. It is set in an unnamed wealthy suburb populated by tech workers that it is difficult not to see as Silicon Valley, and Winnette writes in the cool, wry tone that often signals clear mockery. Miles’s work trajectory, which takes him from creating concepts for online games to masterminding a brand-new virtual-reality pod called the Egg, is well suited to satire: The Egg is precisely the sort of flashy futuristic object that venture capitalists might invest in. But Users isn’t making fun of Miles for inventing it—or making fun of him at all. On its surface, the book seems dry and measured, but at its core, it is a shaky, doubtful, unsettling little book. Users asks its readers to wonder what lurks in the depths of any given person’s mind—or, more alarming, what technology and the Internet may have inserted there—and whether those depths are, perhaps, shallower than they used to be.

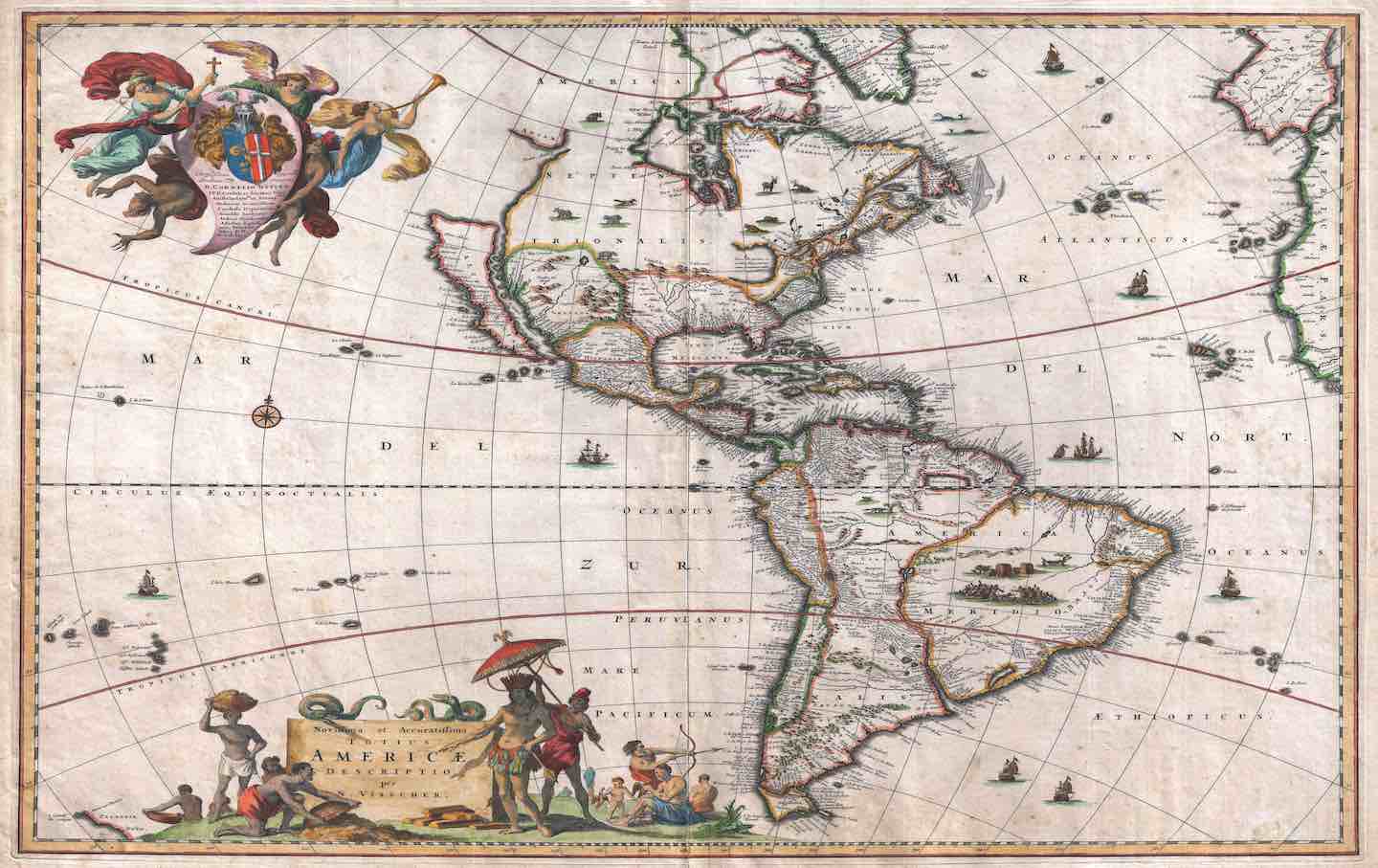

Miles certainly thinks the average citizen is not as imaginative as they should be. At the novel’s start, he is working for a nameless game start-up that hosts a virtual-reality platform in which users “control their environment entirely, from start to finish…. It was a living fantasy, limited only by the speed of your internet”—and, it turns out, by the complexity of your own fantasies. On launching its platform, the company discovers that users need something to “riff on” before they can “dive headfirst into their own imaginations.” Winnette provides almost no examples of the scenarios that Miles’s colleagues create, though he does describe, at length, Miles’s favorite brainchild: The Ghost Lover, a game in which the players are at home, “with things almost exactly as they were in your daily life, only you were being haunted by the ghost of an ex-lover.” Users flock to The Ghost Lover, preferring it to their own scenarios, which tend to involve “sitting in a bathtub at home.”

Miles is both shocked and upset by the lack of creativity in the games that the users create; he is less surprised by that faction of users who attempt to transform the platform into a place to fulfill violent sexual desires. While user-generated scenarios that involve rape are quickly deleted, they remain a persistent problem. Miles sees a frightening version of himself in these users: Although he does not believe that he harbors immoral fantasies, he is afraid that there could be some buried deep inside his brain. In part, this is a pervasive anxiety wedded to modern-day sexual mores, but it is also a germane fear for somebody whose income and status are thoroughly tied to his imagination. If Miles turns out to be a “worse man in his mind than he was in his life”—or even if he imagines something other than what his bosses want—he could lose his whole world without committing a single real breach of decency.

Before working at the tech start-up, Miles wrote for a popular television sci-fi show—which sounds an awful lot like Black Mirror—that spawned an ardent and obsessive fan community. As first a writer and then a game designer, he prizes the ability to roam the “basement level” of his mind, no matter how afraid he is of what he might find there. Winnette first alerts readers to this fear with a scandal: In the book’s opening pages, Miles frets over his recurring donations to a civil rights group whose leader—a man Miles formerly imagined as “a representative of his own conscience”—has been publicly shamed for sending suggestive social-media messages to underage girls. Miles still wants to support the group’s work, but he’s worried that the leader’s poor behavior reflects on him somehow, though he has personally never felt compelled to DM “You are so hawt” to a teenager.

Soon, the players of Miles’s games start amplifying his fear of his own subterranean badness. A faction of users who resent the company’s policy of deleting sexually violent games begin a social-media storm claiming that “haunting…as it occurs in The Ghost Lover, is nonconsensual.” Winnette leaves little doubt about the disingenuousness of this claim, which, like so many other storms of hyperbolic social-media criticism, is rooted in bad faith. Miles recognizes this, but the suggestion that he created an unethical game still rattles him. So does his bosses’ request that he and his creative partner, Lily, come up with something—anything—shiny and new to distract the users, not out of genuine concern but because, as Miles wryly puts it, “while doing the right thing is important to the company, the company needed to exist for the right thing to be done.”

At first, Miles tries to delay fulfilling this mandate by taking his family on a vacation to rural West Texas. The relaxation promised by the remote location quickly goes awry: His younger daughter gets attacked by ants, and his older one becomes alarmingly interested in guns. When Miles pours out his woes to his wife, Claire, she shows him how constrained his imagination has become by fear. He can’t recognize his current task as a unique opportunity to create, backed by “time, resources, and more faith than you probably deserve,” something better than he’s ever made before. Somehow, this declaration works: Miles has a breakthrough; the company strikes it rich(er); the book skips forward several years, and suddenly Miles is no longer creating games but managing the launch of the Egg, which essentially offers its users the opportunity to physically climb inside the Internet.

In the second half of Users, Winnette concentrates on Miles’s transformation into a user. Working on the Egg means he has to subjugate his creative impulses to it, telling himself one ongoing story about the potential it offers rather than spinning new tales constantly. Many readers may recognize in this change an exaggerated version of the real effect of the Internet, which tempts us all to bend our creative projects to suit it, whether that means turning your artwork into NFTs or choosing a bright, blotchy book cover that signifies nothing but performs well on Instagram. Such decisions are often geared toward profit—as is Miles’s investment in the Egg, of course.

For Miles, the Egg makes his job more dependent than ever on the financialization of his creative impulses: He has to come up with the most profitable version of the Egg possible, or his career at the company could be toast. It is unfortunate that Winnette fails to juxtapose this new instability with a direct look at the class issues that seethe beneath the novel’s plot. Running the Egg project makes Miles rich enough to be the sort of person who could, in fact, own an Egg, which is a luxury recreational object that would be easy to get into a Palo Alto mansion but not, say, a two-bedroom in San Jose. But Miles seems hardly to notice that he is designing a future that works only for the elite.

Miles’s downfall ultimately comes about through the Egg, though not from its voyage to the market. Feeling lonely after a bad conversation with his wife, Miles straps himself into an early Egg prototype for a virtual voyage, choosing a game designed by an anonymous user: a meandering drive down a rural road that, as the Egg’s technology accesses Miles’s memories, transforms into the exurban Baltimore of his youth. Soon his wife joins him in the car, which sets off a cascade of worries that, “should he and [Claire] ever divorce, there would be a potential consent issue if the images of her conjured by the Egg too accurately captured her as she would be then, as his ex-wife, rather than simply replicating her as she had been when they were together.” Miles’s concern, with all its tangled conditionals, distracts him from the virtual reality he’s presently in. Without any seeming decision or agency on his part, his virtual self is suddenly getting a real-feeling blow job from the passenger who was until recently his wife, but has transformed into an adolescent who looks distressingly like his oldest daughter.

At this point in the novel, the Egg becomes a proxy for the Internet: a technology that can not only fulfill any curiosity or desire you may have but can also implant new and alarming ones. Yet Users is not only anxious about the Internet’s capacity to change our desires. It also worries over the question—which Winnette leaves intentionally dangling—of whether a horrible fantasy was in fact lurking in Miles’s mind all along. Did it come from his obsessive online reading about the civil rights leader sexting teens? From the Egg? Or was it always his own? Before Miles or the reader can answer these questions, or decide whether the answer matters, his bosses access the record of what happened in the Egg, and Miles is out of a job.

Users tapers to a slow end after Miles gets fired. His wife detaches herself from him; his kids grow distant; and he drifts away from the tech world, though not far. It is not a satisfying ending—nor should it be. Among the novel’s strengths is Winnette’s ability to capture the dissatisfaction that life online generates. While other novelists have focused on the addictive, sickening effects of endless scrolling, Winnette highlights the opposite: the slow numbing of the imagination that comes from hooking it up to machines. He renders this hooking-up literal with the Egg, but really, Miles subjugates himself to technology the moment he begins working in tech. It will not be news to many readers that handing your imagination over to capitalist powers tends to lead to destruction and unhappiness. Even so, Miles’s downward spiral is an effective and upsetting reminder that there’s more to lose on the Internet than just time and money.

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation