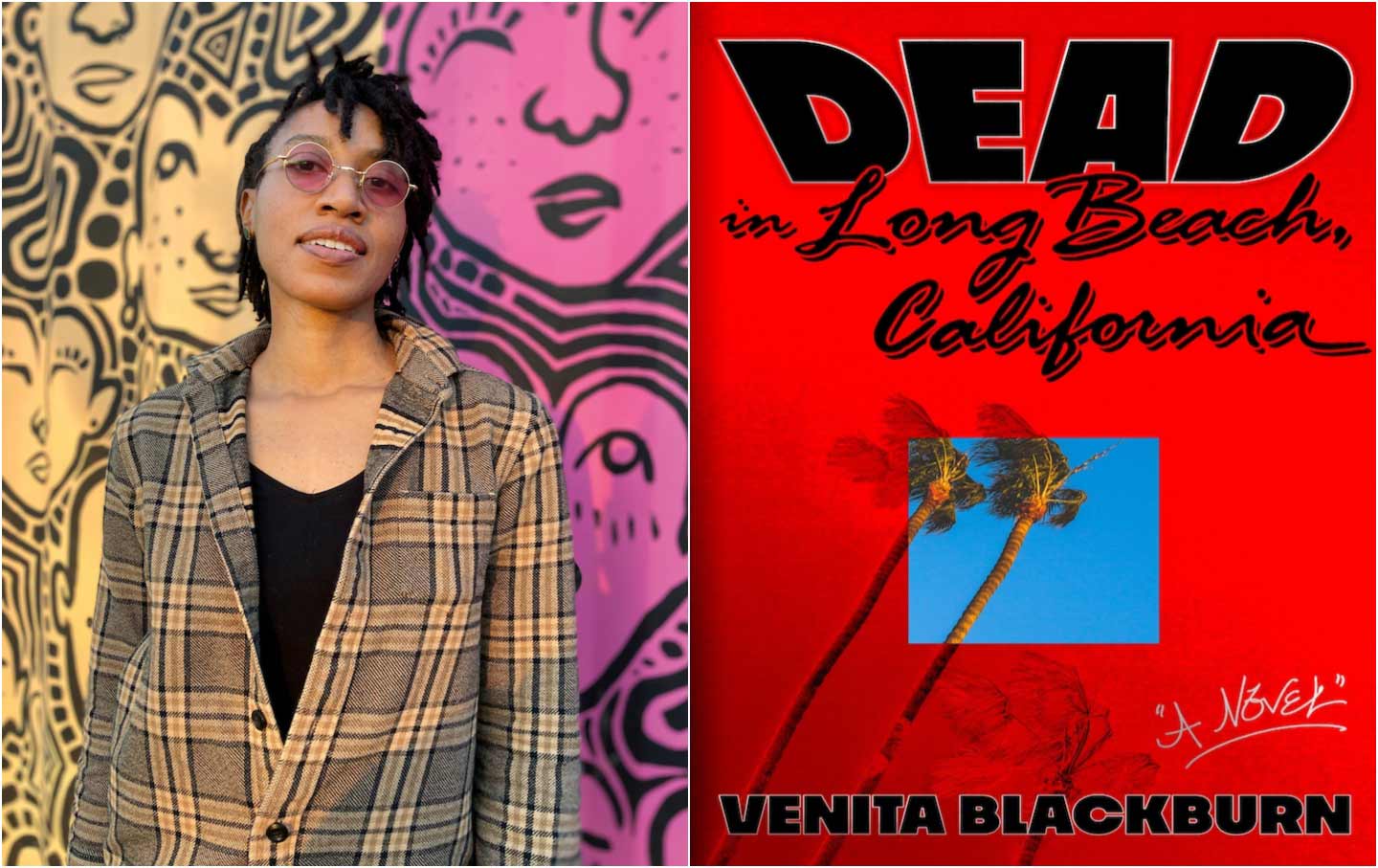

Venita Blackburn’s Stages of Grief

In Dead in Long Beach, California, the novelist looks at how integral lying is to any story we tell about death.

Coral is the first person to discover the body of her brother, Jay, in his apartment in Long Beach. “The studio was dark, the way Jay liked it…and smelled like burned bacon and coconut-scented candles.” The two had spoken minutes before, but Jay never mentioned what he planned to do, commit suicide. Once she enters his apartment, “Coral thought the place was empty but was startled when she saw the shape of Jay under a blanket on his bed.”

Books in review

Dead in Long Beach, California

Buy this bookWhat Coral does next sets the stage for Venita Blackburn’s Dead in Long Beach, California—a debut novel that examines the power of lying and how falsehoods can rewrite the very conditions of our lives. Dutifully, Coral calls 911, but she doesn’t let anyone else know that Jay has died, either friends or kin. Instead, she takes his unlocked phone and begins snooping around.

Jay was the only immediate family member that Coral had left. She thought him a selfish person “who left a mess and a lot of people confused.” Yet he was also the supportive brother who accepted and loved her, even after Coral came out as gay. Jay was also a loving father to his daughter, Khadija, who is estranged from her mother, Naima. Naima, for her part, is “still lost, probably alive, we think, but vanished into the hive of junkies that moved about Los Angeles, always on a mission, always in service to their chemical queen.”

At first, Jay’s life seems isolated and small to Coral as she sifts through her brother’s phone, looking at the limited number of people that he’d remained in contact with. Almost as an attempt to correct this self-isolation, and to refuse the fact that her brother has died, Coral begins to text people from Jay’s phone, as if he were still alive and well. What follows is an exploration of an extreme form of grief, where almost nobody is allowed to grieve besides Coral herself.

Throughout the week that follows her brother’s death, Coral uses his phone, carrying on his life in renewed form. She communicates on an app with Byron, a youth basketball coach and a friend and teammate of Jay’s from decades in the past. Posing as Jay, she makes plans with this old friend to see the Lakers. Coral also reaches out to Kevin, another old friend whom Jay outgrew, one of those men who “remain fourteen for the rest of their lives.” Pretending to be Jay, Coral suggests they go to a strip club together. The point is not necessarily to meet up with these individuals from Jay’s past, but rather to connect once more with the people he had shared his life with, to understand her brother in the context of these other relationships.

Coral, it turns out, is someone with a prolific history of lying. On a bowling date with a woman named Sita, she lied about her career as a writer, claiming that she was a fitness instructor who teaches yoga and Pilates. Then she lied to this woman again, saying that her parents were dentists who met in dental school. These lies are depicted in the novel within a context of “frailty, loneliness, and terror.” For Coral, lies are everywhere, such as giving false names to a barista. Coral is the type of person that sometimes enjoys the rush of telling subtle lies to strangers, reveling in the feeling of becoming “anyone” she wants “during small talk with anonymous individuals.”

Nonetheless, Coral still dreams about “a different world, one where honesty was the cultural norm and no offense would result in retaliation or hurt feelings.” Indeed, Dead in Long Beach, California wants to get to the bottom of how lying can impact a person’s intimate life, in ways both profound and mundane. To approach this question, the novel interweaves three storylines that each look at a different time: the present, the past, and the future. Each strand of this fractured plot accommodates space for varied interpretations of reality—in other words, three storylines of lies.

The first plotline is told largely by an omniscient third-person narrator as Coral, the unpredictable protagonist, moves slowly through each day of the week following her brother’s death. In this part of the novel, Coral manipulates the information surrounding Jay’s suicide because it is one of the few things that she can control in the present tense.

The second plotline is composed of excerpts from a futuristic dystopian novel that Coral has written titled Wildfire. These excerpts appear in a different font to distinguish them from the other parts of Dead in Long Beach. In the world of Wildfire, there is no mention of Coral’s brother, and the resources of the nation seem scarce and depleted and hardly worth living for. There is an overwhelming bleakness that provides insight into how Coral sees the world and where it’s headed next.

The third plotline in Dead in Long Beach is drawn from dissociative, poetic daydreams of a past where Jay is still alive. These flashbacks are distinguished from the other parts of the novel because they begin with the statement “In the Clinic For”—suggesting that memories of Jay aren’t held in isolation but by a community of people—and are written using the “we” pronoun. These kernels from the past are small moments of reprieve, often taking place amid the beauty of California’s landscapes and in familial memories.

Control is lost amid every strand of this story. The fractured form that Dead in Long Beach takes speaks to, embodies, the process of mourning: the restlessness that one can feel when confronting loss; how time can collapse when one is merely attempting to make it from one day to the next.

Yet through her texts to Jay’s contacts, Coral comes to understand “how each of them needed Jay more than they realized and how he needed them too and was always just a few words away.” Upon acknowledging the death of her brother, Coral is able to understand the depth and the importance that his life truly had. For a moment, she is able to see the fullness of her brother’s life.

Ultimately, Coral is forced to confront the truth: No matter how many texts she sends pretending to be Jay, there is no bringing him back from the dead. Coral returns to his apartment, where there is a memorial shrine outside. Khadija is already there and steps outside. The lie finally becomes undone. We end where it all started, at Jay’s apartment, facing his death.

Dead in Long Beach, California reminds the reader how lying shapes one’s intimate life and also how lying is infused throughout the noise of the greater world. At times life is messy, and it feels like “the truth is something for private moments behind one’s eyelids and not for authority figures that might call child protective services.” For Coral, lying has become a survival strategy, and in this novel it takes her everything she has to survive.