Wang Bing, the World’s Hardest-Working Director

In his new film, Youth (Spring), the prolific director examines how the People’s Republic became the workshop for much of the world.

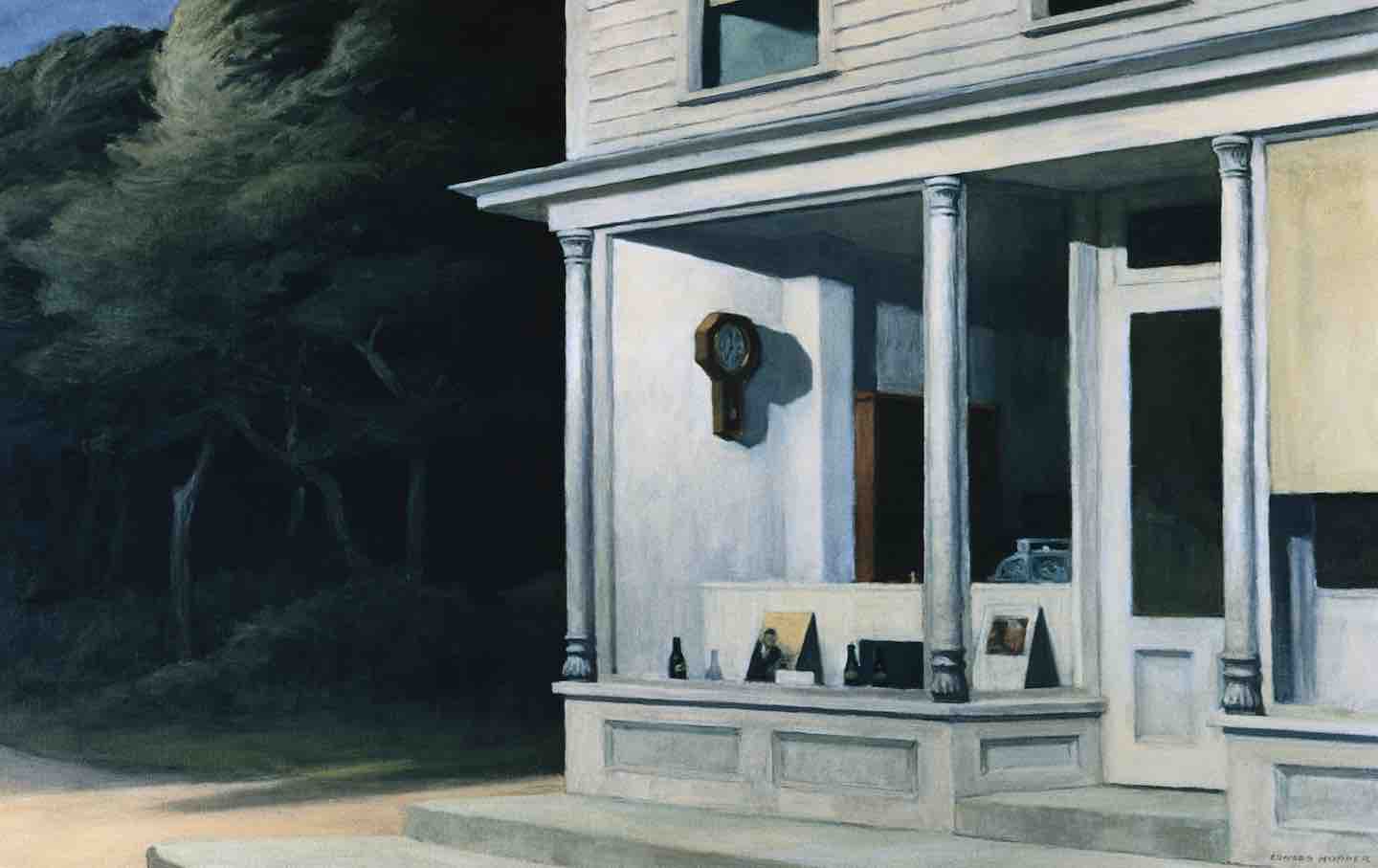

A scene from Youth (Spring).

(Courtesy of Icarus Films)Wang Bing might be the world’s hardest-working filmmaker. Indeed, work is very much his subject. Now 55, Wang began his career with his 2003 Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks, a three-part, nine-hour look at the painful decline of a once-thriving industrial zone, and, in the even longer Crude Oil has documented Mongolian oil-field workers. Relatively short at feature length, his 2010 The Ditch and its eight-hour analogue Dead Souls from 2017 told the story of the survivors of China’s Gobi Desert forced labor camps. More recently, Wang has immersed himself in the lives of migrant workers hired as free agents and paid piece work by sweatshop entrepreneurs.

Shot over a period of four years, his new film, Youth (Spring), draws on the 2,000-plus hours of footage documenting the small sewing factories of northeast China that already yielded Wang’s 2016 Bitter Money. As the title suggests, the workers in Youth (Spring) are mainly in their teens or early 20s. While a few have parents or spouses (and these couples work side by side), most are on their own perhaps for the first time.

Interviewed in Cannes, where Youth (Spring) was shown in competition, Wang explained that youth as a representation of “a revolutionary spirit” is a Chinese cliché, especially in art and that his film intended to “reclaim” it. For him youth is less a political concept than a life-season (the words “Youth” and “Spring” are near synonyms in Mandarin). It is also a state of being. Youth’s spirit and agility are the heart of his film. Riffing while they work, his young subjects impress the viewer with their dexterity. Somehow, they seemed to have blossomed under the sweat shop’s harsh fluorescent light, amid the hallucinatory profusion of mass-produced clothing, to the sound of pounding pop music. Are they producing or being produced?

Wang’s point of view is nominally Marxist (“Human relations today are essentially economic relations,” he’s said) and thus, in the Chinese context, the film is inherently critical. Rather than establish a dictatorship of the proletariat, Youth (Spring) implies, the CCP transformed the People’s Republic into the workshop of the world. And rather than make revolution, its young citizens now make many of the goods that the rest of the world buys. Still, small acts of independence and resistance can be found. The brasher citizen workers cut and stitch with cigarettes dangling from their mouths. Others seem to enjoy negotiating rates, haggling over pay, and arguing with the boss. They understand the concept of surplus value for all the good it does them. No unions here!

As the young workers are warehoused upstairs from their factory, Youth (Spring) is very much concerned with dorm life. The camera tags along and loiters in the narrow corridors, documenting their joshing and fooling around. We are privy to an epic food fight, some drunken confusion, and long waits for the communal bathroom. Tempers sometimes flare (even on the factory floor), but mainly the kids flirt, text, check their phones, try to make dates, and show off for each other and the camera.

Wang, like Frederick Wiseman, is a master of found drama and fly-on-the-wall vérité. Wiseman tends to portray institutions, but, although Wang’s Til Madness Do Us Part is set inside a mental hospital, he is more interested in individual behavior. (His most overtly critical film, the 2007 Fengming, a Chinese Memoir, is a three-hour interview with an elderly woman who, a journalist, who managed to survive the maelstrom of Mao’s shifting policies.)

Youth (Spring)’s opening scene has a 19-year-old boy at one sewing machine and his 20-year-old girlfriend at another in playful competition: “I won!” she exults. We soon learn that this high-spirited girl is two months pregnant. Her parents (up from the country?) want her to get an abortion; the boss insists she complete her quota first. There are also discussions regarding the fate of the hypothetical baby. If the kids marry, which family could claim the grandchild? Twenty minutes into the movie, Wang evokes a situation so emotionally fraught and rich with conflicting obligations (to family and fetus, the state, the boss, one’s partner, oneself) that it could provide the basis for a feature-length documentary essay… and then moves on.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →While one might imagine Wang fulfilling the Neorealism theorist Cesar Zavattini’s idea for a two-hour film about purchasing a pair of shoes, he is more serendipitous. What’s extraordinary, as noted by the Belgian film scholar Camille Bourgeus, is that his “camera enters places of work even when there is nothing out of the ordinary to film.” Moreover, as demonstrated by the foreshortened abortion discussion, he can be abruptly anti-dramatic. His films bristle with broken narrative arcs. Another shop, another story. Youth (Spring) is fascinating because it is potentially endless. Indeed, Wang says he stopped shooting in the sewing factories only because his funding ran out.

There’s a radically Warholian aspect to Wang’s project. Because he favors long takes and close-ups, Youth (Spring) can at times feel like a series of screen tests—not least in that, like Warhol’s, his is to a degree a film about people being filmed. Although the filmmaker’s presence may be sensed and is sometimes acknowledged, Wang’s subjects appear largely indifferent to his attention. Is he simply a human manifestation of Chinese social media or China’s extensive surveillance network? Do they take him for a cop, a talent scout, a fellow worker? How does he explain his presence? How do we?

Wang declines to submit his films for official approval, and none have been shown commercially in China. In a discussion regarding Bitter Money, a filmmaker from India told me that in his view Wang was a fraud who simply packages misery for the delectation of Western cineasts. It is true that Wang gets much of his support from French, German, and Dutch TV and that he clearly times his films for European festival release. But does that mean he is an artist whose sole desire is to please his patrons? Or that his powerful chronicles of Chinese life do not celebrate those who are chronicled in them?

Three Sisters, Wang’s magnificent 2012 portrait of young children in a subsistence-level village in Yunnan province, largely fending for themselves after their father has gone to the city to work (perhaps in a sewing factory), is set, per the filmmaker, in “a poverty-stricken environment.” But rather than an exposé of poverty, he has said Three Sisters is “about the lived experience of the girls’s existence.” Lived experience is the essence of Youth (Spring) as well as it is of Wang’s project. As a filmmaker he embeds himself in China’s working classes, working his own trade alongside them.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation