Ghosts of the Past

The cinema of ordinary fascism.

Steve McQueen and Jonathan Glazer Confront the Holocaust

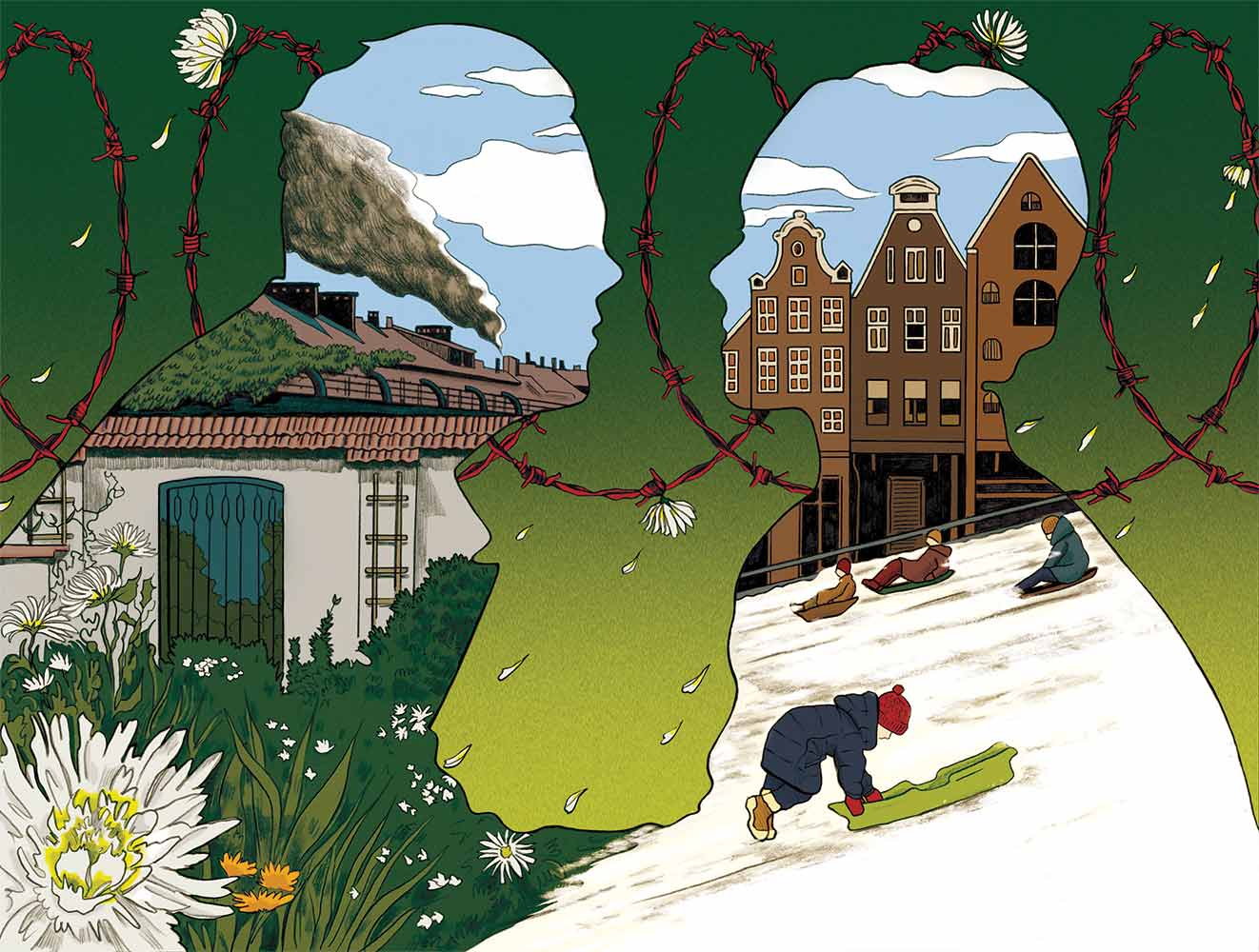

In Zones of Interest and Occupied City, the two filmmakers attempt to depict the ordinary fascism and everyday violence of World War II.

Hannah Arendt’s long-ago characterization of the Nazi desk murderer Adolf Eichmann as personifying the “banality of evil” has itself became banal, but a truism isn’t necessarily untrue. Everyday terror is everywhere manifest, perpetrated by dull functionaries unimaginative enough to regard themselves as exemplary in their devotion to their jobs. Eichmann’s colleague and collaborator Rudolf Höss demonstrated this pathology in his death-house memoir, posthumously published as Commandant of Auschwitz. A witness for the prosecution at Nuremberg, Höss apologized for the terrible actions conducted under his command but never accepted personal responsibility. Instead, like Eichmann, he insisted that he was merely fulfilling his duties.

Reading Höss’s memoir, as Primo Levi noted, can be “oppressive.” Commandant of Auschwitz “is full of vileness recounted with a disturbing bureaucratic obtuseness,” Levi wrote, and yet it is “one of the most instructive books ever to have been published.” A “careerist of moderate ambition,” Höss “was not made of different clay from any other member of the bourgeoisie in any other country.” Society has no shortage of unconscionable sociopaths passing for normal; it’s the magnitude of Höss’s and Eichmann’s crimes that confounds the mind. The industrial murder of millions committed by the Nazis and their accomplices is a defining catastrophe of the catastrophic 20th century. The combination of merciless slaughter and bureaucratic banality is also the subject of two remarkable new films: Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest and Steve McQueen’s Occupied City.

Both filmmakers—who have had wide and varied careers as indie and blockbuster directors—appear acutely mindful of Claude Lanzmann’s monumental Shoah. Like Shoah, both of these films use indirection to make the Holocaust present in disturbingly detailed studies of routine extermination. The Zone of Interest depicts a married couple whose comfortable life is underwritten by the largest and most efficient of the Nazi death camps; Occupied City documents a European capital full of willing participants in, or willful indifference to, the eradication of the city’s Jewish population. Sticking closely to the known facts, Glazer provides insight into the domestic life of a genocidal administrator. Detached and unemotional, McQueen annotates ordinary street scenes in present-day Amsterdam with the murderous activities that transpired there under German occupation.

Neither fiction nor documentary, The Zone of Interest and Occupied City are essays, each in its own way attesting to the apparent ease with which humans can deprive others of even their basic humanity and exploring the dialectical relationship between banality and evil. Either film could have justly appropriated the title of Soviet director Mikhail Romm’s 1965 compilation of Nazi newsreels, Ordinary Fascism.

More than ordinary, the married couple in The Zone of Interest are Rudolf Höss and his wife, Hedwig, who live in a villa taken from a Polish family just outside one of the entrances to Auschwitz. The movie takes its setting and title, but little else, from Martin Amis’s 2014 novel of life and love among the genocidaires. (“The Zone of Interest” was the Nazi euphemism for the restricted area around Auschwitz.) But while the Amis novel is a high-wire stunt that could only have been performed without the author looking into the abyss, there are no free passes in Glazer’s Zone. Where Amis can be playful and even humorous, Glazer is sober, if not without his own sense of irony. The movie’s deadpan press release tells it all: “The commandant of Auschwitz, Rudolf Höss, and his wife Hedwig, strive to build a dream life for their family in a house and garden next to the camp.” It could be a Lenny Bruce one-liner.

The Zone of Interest opens with the Hösses picnicking by a lake. Summer is in bloom. The sky, at least in this scene, is unblemished by smoke. Still, the birdsong can’t quite obscure the noise of barking dogs and the muted cries that are constant throughout the movie. (The movie’s propulsive sound design is an essential element in Glazer’s argument.)

For its first hour, The Zone of Interest restricts itself to this bucolic fantasy. Observing the Höss family at home and in their garden, we watch them tend to their extraordinarily tidy estate, protected by a barbed-wire barrier and all but nestled against the walls of the combination slave-labor factory and death camp. Glazer’s brilliance as a director is to place Rudolf (Christian Friedel) and Hedwig (Sandra Hüller) under our constant observation. We watch them go about their domestic routines, filmed with hidden cameras under natural lighting. Children frisk in the garden, which even has a little swimming pool. A few terrorized Polish servants scurry furtively about, giving chez Höss the feel of a modest antebellum Southern plantation.

Like the Höss family, we are shielded when the commandant goes to work, riding his horse a ridiculous few yards to the Auschwitz gate. Only once are we are permitted—in a sudden, shocking mega-close-up—an intimation of what happens inside the camp. (The frame is tight, the noise deafening, the only image a close-up of Höss’s face.) Otherwise, the nature of his job is communicated solely through bureaucratic euphemism. Toasted on his 43rd birthday, Rudi takes a business meeting to discuss the construction of a new crematorium, with particular emphasis on its capacity for “loads” and its efficiency in processing “pieces.”

Meanwhile, the family lounges around the garden or bustles about its ostentatiously spotless home. Hedy models a confiscated fur coat and applies the lipstick found in its pocket, then goes downstairs to host a kitchen kaffeeklatsch with the other Auschwitz wives. They discuss the bounty that turns up in the camp warehouse, dubbed “Kanada,” gossiping about a friend’s inability to squeeze into a dress that had formerly belonged to “some little Jewess.” Hedy later hosts her mother, who has traveled from Germany for a visit, and idly wonders if the rich Jewish woman whose house she used to clean might be on the other side of the fence. Mainly, they talk about Hedy’s good fortune. “Rudi calls me the Queen of Auschwitz,” she laughs.

Höss is not only attentive to Hedy; he is also filled with concern for his five children—never more so than when, paddling in the Soła River, two of them are coated with soot that an errant breeze has wafted over from the camp. The more distant parent is Hedy, whose selfishness may be her most human characteristic and which drives perhaps the movie’s central scene (based, according to Glazer, on testimony from the Höss family gardener). Learning that Rudi is being transferred from Auschwitz to a new position in a suburb outside Berlin, Hedy freaks: “You can’t do this to me!” she cries, then instructs her husband to go to Hitler and have the order changed. “They’ll have to drag me out of here!” she insists. (Again, one thinks of Lenny Bruce.)

The precise, antiseptic mise-en-scène (reminiscent in some ways of Stanley Kubrick) is reinforced by the immaculate cleanliness of the Hösses’ home and the film’s unobtrusive, perfectly placed metaphors: a clothesline with fresh linen stirring in the breeze, the commandant blindfolded for his birthday surprise, the two little Höss boys playing with tin soldiers. Missing, of course, is the smell of death, although the Höss family’s intermittent references to pleasant olfactory sensations (flowers, perfume) suggest a capacity to shut out offensive aromas.

Glazer, 58, is a filmmaker with a knack for making his ideas physical. The Zone of Interest is his first feature since 2013’s Under the Skin, a horror film at once visceral and cerebral. Briefly described, it concerns a predatory extraterrestrial who has assumed the form of an attractive young woman (Scarlett Johansson) and is cruising Glasgow looking for male victims. Typically, Glazer’s movies address their subjects from an unusual angle. His first, Sexy Beast, was a showy gangster film predicated on a terrifyingly violent performance by the man who played Gandhi, Ben Kingsley; his second, Birth, was a Jamesian psychological/supernatural thriller with sudden eruptions of taboo-breaking mayhem. The critic Thomas Puhr compared Glazer’s earlier films to a lake “whose surface remains calm and untouched so that we can better see our reflections in it,” and that may be most true with The Zone of Interest: It is a movie that prompts contemplation even as it inspires disgust.

To a degree, Glazer’s strategy of indirection was anticipated some 45 years ago by Theodor Kotulla’s little-known Death Is My Trade, a two-and-a-half-hour West German telefilm that recounted Höss’s progress from disoriented World War I veteran to the man who built Auschwitz. A critic turned filmmaker, Kotulla much admired Robert Bresson, and one can find Bresson’s influence in the film’s non-emotive acting and ascetic staging. The understatement of its German title, which can be translated as Scenes From a German Life, suits the provocatively neutral, distanced style.

I saw Death Is My Trade years ago and remember being angered by Kotulla’s seeming refusal to acknowledge Höss’s victims until the final scenes, when the camera tours present-day Auschwitz. I did not get Kotulla’s decision to forestall his German audience from regarding Höss’s ordinary “German life” through eyes misty with crocodile tears. The Zone of Interest changed my mind about Kotulla’s approach. With no alternate figures of identification besides Rudi and Hedy, the movie offers a test for its audience, posing all manner of questions, including some about the viewers themselves and the film as well.

Can indirection convey the full horror of the subject? Are the soldiers who direct drones thousands of miles away also desk murderers? At what point does garden-variety selfishness become truly evil? Is the concept of lebensraum specifically German? It is impossible to listen to the Hösses speak of the “settler” dreams that Hitler promised them without thinking of the role of settlers in American history, colonial Africa, or the occupied West Bank. To what degree do we also live comfortably in and profit from a state of historical denial?

Höss described himself as an efficiency expert: “To fulfill my duties adequately, I had to become the motor that tirelessly and restlessly regenerated impulses to work at building the camp. I had incessantly and repeatedly to drive every inmate onward, to haul SS men and prisoners forward together.” Had he not created the greatest extermination center of all time, eliminating the bloody mess of machine-gunning prisoners?

The Zone of Interest ends with Höss proudly tackling his ultimate assignment: the liquidation of 700,000 Hungarian Jews. That this is regarded as an abstract problem to be solved may be the most shocking example of the compartmentalizing bureaucratic mindset. Höss, it is clear, hated even thinking about the actuality of mass murder. “The most repugnant pages” of Höss’s book, as Levi noted, were “those in which Höss lingers over descriptions of the brutality and indifference with which the Jews charged with clearing out bodies go about their work.” His brutality and indifference are of a different order.

In a throwaway gag swiped from Amis’s novel, Glazer has Höss (always the convergent thinker) gaze at a ballroom filled with Nazi functionaries and idly ponder the logistics of gassing them all. Soon after leaving the reception, where he has perhaps had too much to drink, Höss heaves and retches. Is he really sickened? Rather than a demonstration of pitifully inadequate humanity, the action seems performed on behalf of the spectator.

At least since Shoah, any motion picture addressing a world-historic atrocity must grapple with the ethics of representation. Steve McQueen had already confronted these difficulties in 12 Years a Slave, which evoked the enormity of slavery by focusing on a single ordinary individual and plunging him and the viewer into a nightmare of dehumanization. In that earlier film, McQueen presents a brutally Kafkaesque existential ordeal; in his new four-and-a-half-hour documentary Occupied City, heemploys another strategy, overwhelming the spectator with data at once banal and extraordinary.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Like The Zone of Interest but differently, Occupied City portrays ordinary fascism, as a variety of everyday people turn on their neighbors, coworkers, and friends. Inspired by his wife Bianca Stigter’s Atlas of an Occupied City, Amsterdam 1940–1945, McQueen presents footage of contemporary Amsterdam accompanied by a neutral voice-over litany of the wartime betrayals, arrests, and roundups of Dutch Jews and resisters. There is no archival footage of these scenes. The question McQueen asks is how—or if—these historical crimes have been inscribed in the present.

Occupied City is not linear, and the correlation between what is shown and what is told is inconsistent. Stigter’s book systematically maps out Amsterdam street by street, but rather than an atlas, Occupied City is a mass of anecdotes. The viewer tunes in and out as McQueen’s camera wanders through the city, creating a double vision—past/present and sound/image—but only sometimes producing a sense of historical depth.

Yet this seemingly haphazard lack of resolution is significant. McQueen’s film re-creates the lack of interest that many if not most Dutch felt regarding the Jews and resisters being flushed out of their homes. The Netherlands did not have a sterling wartime record: The survival rate among Dutch Jews was the lowest in Western Europe, far worse than in Belgium or France. Amsterdam had a population of 800,000, and some 10 percent of them were Jews, three-quarters of whom died during the Holocaust.

Given that the story of the Holocaust that McQueen tries to tell here is one of indifference as well as action, his film might more accurately be called Preoccupied City. We hear of resistance fighters being arrested and watch children ice-skating and sledding. Descriptions of massacres are accompanied by images of heedless young people congregated in a park.

Some of the juxtapositions prove ironic: A Jewish couple’s suicide note, inviting neighbors to help themselves to their belongings, is read against images of the ordinary mail being delivered to that very same nondescript apartment building. On the other hand, the present is also present: Dam Square, the location of many pro-Nazi rallies, now serves as the site for a climate justice demonstration. Other juxtapositions seem random, thus allowing for all manner of chance synchronicities. Occupied City was shot in the middle of the pandemic and features televised Covid warnings, lockdowns, masked cops, and curfews (the first since World War II), as well as placards demanding “Stop Covid Lies Now”—free-floating signifiers of another sort of occupation.

An account of mass deportation accompanies footage taken in a geriatric hospital—a startling image of doomed people waiting for death. We see a high school that once served as Gestapo headquarters. These moments are sudden shock therapy. Yet while Occupied City succeeds in conjuring trauma and releasing the ghosts of the past, the effect is more transitory than cumulative.

Speaking at the New York Film Festival this fall, McQueen and Stigter suggested that Occupied City was itself intended as a monument. If so, it is a less successful one than Stigter’s Three Minutes: A Lengthening, which extended a scrap of film taken in a pre–World War II Jewish town into a feature-length analysis. But it does intermittently succeed in lifting the veil of normal, present-day Amsterdam to reveal the terror behind it.

By contrast, The Zone of Interest accomplishes something different in its final minutes. From its hour-and-40-minute immersion in the Nazi past, the film abruptly flashes forward to the present—or, from the perspective of its narration, visits the future. A brief coda documents the custodial staff preparing the Auschwitz Museum to open for the day, with the camera pondering the interior of the crematoria as well as a narrow corridor flanked with floor-to-ceiling vitrines containing tens of thousands of shoes and crutches, residues of Höss’s victims. For hours, Occupied City conjoins the banal present and the painful past. The Zone of Interest is more economical: The past has been rendered so immediate and familiar that, at the end, it is jarring to see it memorialized.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks

The late actor and director leaves behind a roster of classic films—and a much safer and juster California.

Solution to the “Big Event” Crossword Solution to the “Big Event” Crossword

If questions remain after reading this, please write to sandy @ thenation.com.

Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments

Dev Hynes moves between grief and joy in Essex Honey, his most personal album yet.