Donald Trump’s Retrograde Worship Will Tank America’s Auto Industry

Trump’s tariffs will protect the US auto industry just long enough for it to decline into technological obsolescence.

Pioneer Natural Resources equipment near Midland, Texas, on Wednesday, October 11, 2023.

(Michael Ciaglo / Bloomberg / Getty Images)

This article originally appeared at TomDispatch.com. To stay on top of important articles like these, sign up to receive the latest updates from TomDispatch.com.

It came upon a midnight clear, a vision both complete and quite specific—not from any of those “angels bending near the earth to touch their harps of gold,” as in the Christmas carol, but from a long line of trucks on the Indiana Toll Road.

On that cold winter’s night about five years ago, the 18-wheelers were playing their usual game to stay awake, passing each other endlessly and slowing me down to 60 miles an hour when I wanted to do 70 or, I’ll admit it, 75. When I pulled into a rest stop to gas up, about 50 of those big rigs were parked there. Their drivers were taking the federal government’s mandatory 11- or 12-hour rest breaks.

A quick bit of mental arithmetic told me that 50 big rigs, each costing $200,000 new, meant that $10 million in working capital was snoozing profitlessly by the side of that road. Back on the highway in a radio-dead zone, my mind wandered as I wondered just how many trillions of dollars in capital were tied up when America’s three million big rigs spent half their working days functionally asleep. Surely, I thought, there must be a better way to run the world’s biggest consumer economy.

As I hit the Chicago Skyway with its rough pavement and rusting guard rails, a vision of America’s automotive future came to me in a flash, complete in every detail. One day in the not-too-distant future, the left lane of every Interstate highway across America would be filled with platoons of a dozen or so 18-wheelers, all electric, all driverless, going 70 miles per hour only 10 feet apart to draft in the slipstream and cut their energy consumption by 30%. In the right lanes, electric passenger vehicles would be driving, hands-free, until they reached their exit ramps. To keep the navigation signal constant, the highway reflectors would have become wireless transmitters, linked by fiber-optic cables to ensure safety.

Then, as I merged into that crazy-fast nighttime traffic on Chicago’s Kennedy Expressway, I came up with what I thought was my really big idea. Outside every major city, those all-electric big rigs would pull into an automated depot to exchange their standard-sized batteries, allowing a full charge in five minutes. There, human truckers, probably more of them than ever before, would take over, navigating crowded city streets and tight loading docks with hard-won skills that no robot could ever replicate.

When I got home to Madison, Wisconsin, late that night, I went online to test my vision with some quick numbers. In 2020, the costs for a big rig’s driver, fuel, and engine maintenance were as much as $2.20 a mile, so a typical thousand-mile run from Port Newark on the East Coast to Chicago could cost $2,200. By contrast, a driverless electric semi-slipstreaming in a peloton would make the same trip for just $70—with the cost of drivers at near-zero, energy outlays down to five cents per mile, and maintenance reduced to tire replacement—not to mention the incalculable gains from doubling each rig’s driving time to 24/7.

Vision Becomes Reality

Until recently, I kept that midnight vision to myself, except for an occasional dinner-table chat after a second glass of wine. Frankly, it all seemed a bit much for prime time. Even electric passenger vehicles, much less semi-trucks, faced two key barriers to widespread acceptance in America—range and cost. In the upper Midwest where I live, a cold winter’s day can cut the 300-mile range of an electric car like a Tesla to just 150 miles. Although I could make the 250-mile drive in an electric vehicle from the state capital of Madison to hike or ski in Northwoods Wisconsin, there’s no public charger anywhere nearby. So there’s no way to get back. And cost? While you can get a reliable gas-powered Honda Civic for $24,000, a comparable electric vehicle like the Hyundai Ioniq now costs $39,000.

But just last week, I was surfing the EV (electric vehicle) test drives in Edmunds and Kelly Blue Book when a web page popped up with the title “7 Long-Range Electric Cars from China.” I was stunned to read that a car I’d never heard of, the NIO ET7, comes with a standard 649-mile range and complimentary access to “3,000 battery swap stations across China.”

Was my midnight vision becoming clearer? Yes, the article said, “the battery swap stations allow you to exchange your depleted battery for a fully charged one in just a few minutes, minimizing downtime.” Another cutting-edge Chinese car few in America have ever heard of, the ZEEKR 001, can load a 300-mile charge in 11 minutes flat, less time than it takes to pump an equivalent-mileage of gas. And a Chinese car unknown here, the XPENG P7, has an innovative battery that “operates optimally” in temperatures ranging down to –22° Fahrenheit, ending the cold weather battery loss that makes EV driving so frustrating in Midwest winters.

And what about their price? While Detroit is maxing profits by pricing the tricked-out Ford F-150 Lightning EV truck for $87,000 and GM’s similar Silverado EV costs $96,000, China has gone back to basics with a latter-day Model T Ford—reliable, affordable cars for the average worker.

European companies were hand-crafting cars for the rich as early as 1890. The Detroit auto industry didn’t get a jump-start until 1908 when Henry Ford mass-produced the Model T for what began as a reasonably affordable $850 and soon had dropped to $345—unprecedented pricing that ramped that car’s production relentlessly up to an impressive two million units a year. In just 10 years, half of all the cars in America were Model Ts.

Following Ford’s time-tested lead, China’s largest automaker, BYD, is selling its Dolphin hatchback EV for a low-low $15,000, complete with a 13-inch rotating screen, ventilated front seats, and a 260-mile range. Here in the United States, you have to pay more than twice that price for the Tesla Model 3 EV ($39,000) with lower tech and only 10 more miles of driving range. In case $15K beats your budget, the Dolphin has a plug-in hybrid version with an industry-leading 74-mile range on a single charge for only $11,000 and an upgrade with an unbeatable combined gas-electric range of 1,300 miles. Not surprisingly, EVs surged to 52 percent of all auto sales in China last year. And with such a strong domestic springboard into the world market, Chinese companies accounted for more than 70 percent of global EV sales.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →It’s time to face reality in the world of cars and light trucks. Let’s admit it, China’s visionary industrial policy is the source of its growing dominance over global EV production. Back in 2009-2010, three years before Elon Musk sold his first mass-production Tesla, Beijing decided to accelerate the growth of its domestic auto industry, including cheap, all-electric vehicles with short ranges for its city drivers. Realizing that an EV is just a steel box with a battery, and battery quality determines car quality, Beijing set about systematically creating a vertical monopoly for those batteries—from raw materials like lithium and cobalt from the Congo all the way to cutting-edge factories for the final product. With its chokehold on refining all the essential raw materials for EV batteries (cobalt, graphite, lithium, and nickel), by 2023–24 China accounted for well over 80 percent of global sales of battery components and nearly two-thirds of all finished EV batteries.

Clearly, new technology is driving our automotive future, and it’s increasingly clear that China is in the driver’s seat, ready to run over the auto industries of the United States and the European Union like so much roadkill. Indeed, Beijing switched to the export of autos, particularly EVs, to kick-start its slumbering economy in the aftermath of the Covid lockdown.

Given that it was already the world’s industrial powerhouse, China’s auto industry was more than ready for the challenge. After robotic factories there assemble complete cars, hands-free, from metal stamping to spray painting for less than the cost of a top-end refrigerator in the US, Chinese companies pop in their low-cost batteries and head to one of the country’s fully automated shipping ports. There, instead of relying on commercial carriers, leading automaker BYD cut costs to the bone by launching its own fleet of eight enormous ocean-going freighters. It started in January 2024 with the BYD Explorer No. 1, capable of carrying 7,000 vehicles anywhere in the world, custom-designed for speedy drive-on, drive-off delivery. That same month, another major Chinese company you’ve undoubtedly never heard of, SAIC Motor, launched an even larger freighter, which regularly transports 7,600 cars to global markets.

Those cars are already heading for Europe, where BYD’s Dolphin has won a “5-Star Euro Safety Rating” and its dealerships are popping up like mushrooms in a mine shaft. In a matter of months, Chinese cars had captured 11% of the European market. Last year, BYD began planning its first factory in Mexico as an “export hub” for the American market and is already building billion-dollar factories in Turkey, Thailand, and Indonesia. Realizing that “20 percent to 30 percent” of his company’s revenue is at risk, Ford CEO Jim Farley says his plants are switching to low-cost EVs to keep up. After the looming competition led GM to bring back its low-cost Chevy Bolt EV, company Vice President Kurt Kelty said that GM will “drive the cost of E.V.s to lower than internal combustion engine vehicles.”

Will Tesla Be Toast?

What about Tesla, America’s pioneering EV maker? With its CEO Elon Musk off playing pretend president, its worldwide vehicle deliveries fell last quarter for the first time in a decade, even as BYD’s global sales shot up 12 percent to 1.76 million, beating Tesla by a 20 percent margin to become the world’s biggest EV car-maker. Even though Tesla still accounts for almost half of this country’s EV sales and has a current market capitalization of $1.3 trillion, Musk’s model line-up now seems increasingly outmoded, over-priced, and unappealing, exemplified by his latest launch, the “weird” Cybertruck with a “nonsensical exterior,” which starts at $82,000 for a minimal 330-mile driving range. Even though Tesla is still the world’s “most valuable automotive brand,” stock pickers and short-sellers take note: its car sales could be toast within five years, though its still-small division making electrical semi-trucks has real growth potential. (And take note as well that I’m not giving stock advice, just making a point on where I think our world’s heading.)

Realizing that their auto industries are facing a carmageddon of Chinese competition, the United States and Europe are already slapping heavy tariffs on imports from China. With its robotic factories cranking out one complete car every 76 seconds, China is ready to crush rival car companies and build 80 percent of all the world’s autos, as it already does with solar panels. Last June, the European Union imposed additional duties of 17 percent on China’s BYD and 38 percent on SAIC, but the Biden administration had already beaten that with a flat 100 percent duty on all Chinese EVs. And count on one thing: That’s just the start. In his second term in office, Donald Trump has already promised an additional 10 percent tariff on all Chinese imports, cars included—protecting the US auto industry just long enough for it to decline into technological obsolescence.

In our integrated global economy, cars are a commodity like copper, oil, food, or textiles. In capitalist societies, commodities are not just products but the sinews that bind together nations on an otherwise disparate planet and a force like water that always finds its own level. Even if those tariffs manage to keep American workers buying overpriced, outmoded vehicles, the big four of the US auto industry—Ford, GM, Stellantis, and Tesla—can hardly afford to lose their overseas markets. Last quarter, China’s motorists accounted for a hefty 40 percent of Tesla’s total worldwide sales, so Elon Musk faces an impossible contradiction: how to get President Trump to protect his US market with high tariffs on Chinese cars while somehow avoiding Beijing’s wrath. Finding a way through that conundrum will likely prove challenging for Tesla.

Autos and America’s Future

So, what does all this mean for America? In the past four years, the Biden administration made real strides in protecting the future of the country’s auto industry, which is headed toward ensuring that American motorists will be driving $10,000 EVs with a 1,000-mile range, a 10-year warranty, a running cost of 10 cents a mile, and 0 (yes zero!) climate-killing carbon emissions.

Not only did President Biden extend the critical $7,500 tax credit for the purchase of an American-made EV, but his 2021 Infrastructure Act helped raise the number of public-charging ports to a reasonable 192,000, with 1,000 more still being added weekly, reducing the range anxiety that troubles half of all American car owners. To cut the cost of the electricity needed to drive those car chargers, his 2022 Inflation Reduction Act allocated $370 billion to accelerate the transition to low-cost green energy. With such support, US EV sales jumped 7 percent to a record 1.3 million units in 2024.

Most important of all, that funding stimulated research for a next-generation solid-state battery that could break China’s present stranglehold over most of the components needed to produce the current lithium-ion EV batteries. The solution: a blindingly simple bit of all-American innovation—don’t use any of those made-in-China components. With investment help from Volkswagen, the US firm QuantumScape has recently developed a prototype for a solid-state battery that can reach “80% state of charge in less than 15 minutes,” while ensuring “improved safety,” extended battery life, and a driving range of 500 miles. Already, investment advisors are touting the company as the next Nvidia.

But wait a grim moment! If we take President Donald Trump at his word, his policies will slam the brakes on any such gains for the next four years—just long enough to potentially send the Detroit auto industry into a death spiral. On the campaign trail last year, Trump asked oil industry executives for a billion dollars in “campaign cash,” and told the Republican convention that he would “end the electrical vehicle mandate on day one” and thereby save “the U.S. auto industry from complete obliteration.” And in his victory speech last November, he celebrated the country’s oil reserves, saying, “We have more liquid gold than anyone else in the world.”

Then, just last month, president-elect Trump “vowed” to repeal Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act and its $400 billion in unspent funds for green energy, while his transition team began to plan a “sweeping rollback” of federal support for the adoption of EVs—including shifting charging-station appropriations to defense, blocking California’s strict emission standards, and ending the $7,500 tax credit that has made EVs affordable for many Americans. More broadly, he’s promised to reverse Biden’s ban on oil leases in federal waters, saying just this month: “It’s ridiculous. I’ll unban it immediately. It’ll be changed on Day One.”

But, you might protest, it’s only four years, right? How much damage can be done in just one itty-bitty presidential term? The answer is all too grim: with technology passing us at 100 miles an hour, four years isn’t a term; it’s an era, a veritable epoch. Think back to 2020. Worldwide EV sales were just 1.6 million then; now they’re up ten-fold to 16.6 million and rising fast. Chinese motorists bought just one million EVs in 2020; now they’re buying 10 million a year. Then, the reasonably affordable 2020 Hyundai Ionic EV had a relatively useless driving range of 133 miles; now, it has a very usable 342 miles. Back in that day, QuantumScape’s extended-range solid-state EV battery seemed so improbable it was damned by stock-pickers as “a pump and dump… scam”; now Volkswagen is taking that company’s prototype into mass production.

So here’s the reality of it all: the loss or even weakening of the US auto industry would have a devastating effect on this country’s economy and its quality of life. At the moment, the industry employs 13 million workers, including one million in manufacturing. We’re talking about a solid 10 percent of the country’s full-time workforce of 133 million.

Under their 2023 union contract, striking unionized UAW auto assembly workers won an hourly wage of $35 and skilled trades got $50, which is a gate pass into the American middle class. Not only did President Biden join a UAW picket line with striking auto workers, but he engineered a full-spectrum transition to EVs, understanding that they represent the future of the auto industry. Indeed, as Biden explained while signing a 2021 executive order requiring that 50 percent of all cars sold in America by 2030 be EVs: “We need to grow good-paying, union jobs at home, lead on electric vehicles around the world, and save American consumers money.” As Biden all too accurately reminded that UAW picket line at the Willow Run GM plant: “The middle class built the country, and unions built the middle class.”

During his upcoming four-year term, despite the present support of Elon Musk—and who knows how long he’ll last in Trump world—President Trump has made it clear that he will undo all of that, promote fossil fuels in a massive fashion, ignore climate change, and potentially hand the economic future to China (which already makes 80% of the world’s solar panels and 60 percent of its wind turbines), while creating a carmageddon for this country’s auto industry.

And what about my midnight vision of that peloton of all-electric, driverless semi-trucks slipstreaming down the Interstate at 70 mph? Yes, it’s coming. But with Trump as our driver for the next four years, we can only pray to those angels with the golden harps that electric semi-trucks and their batteries will somehow, someday, be made in America.

Support independent journalism that exposes oligarchs and profiteers

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

To Defeat the Far Right, We Must Adopt an Anti-Fascist Economic Policy To Defeat the Far Right, We Must Adopt an Anti-Fascist Economic Policy

Opposition to the status quo must not be monopolized by the right-wing extremist visions of parties like Alternative für Deutschland.

Trump’s Greenland Obsession Is All About China Trump’s Greenland Obsession Is All About China

Greenland and its resources are merely the latest potential casualty of Trump’s quest for global domination and his fear of China’s economic power.

Trump Is Fumbling the NLRB. But Amazon Workers Can Still Build Momentum. Trump Is Fumbling the NLRB. But Amazon Workers Can Still Build Momentum.

Amazon Teamsters’ December strike was the biggest in the company’s history. What does their future look like under Trump 2.0?

Welcome to the New Military-Industrial Complex Welcome to the New Military-Industrial Complex

An assortment of new firms, born in Silicon Valley or incorporating its disruptive ethos, have begun to challenge the older ones for access to lucrative Pentagon awards.

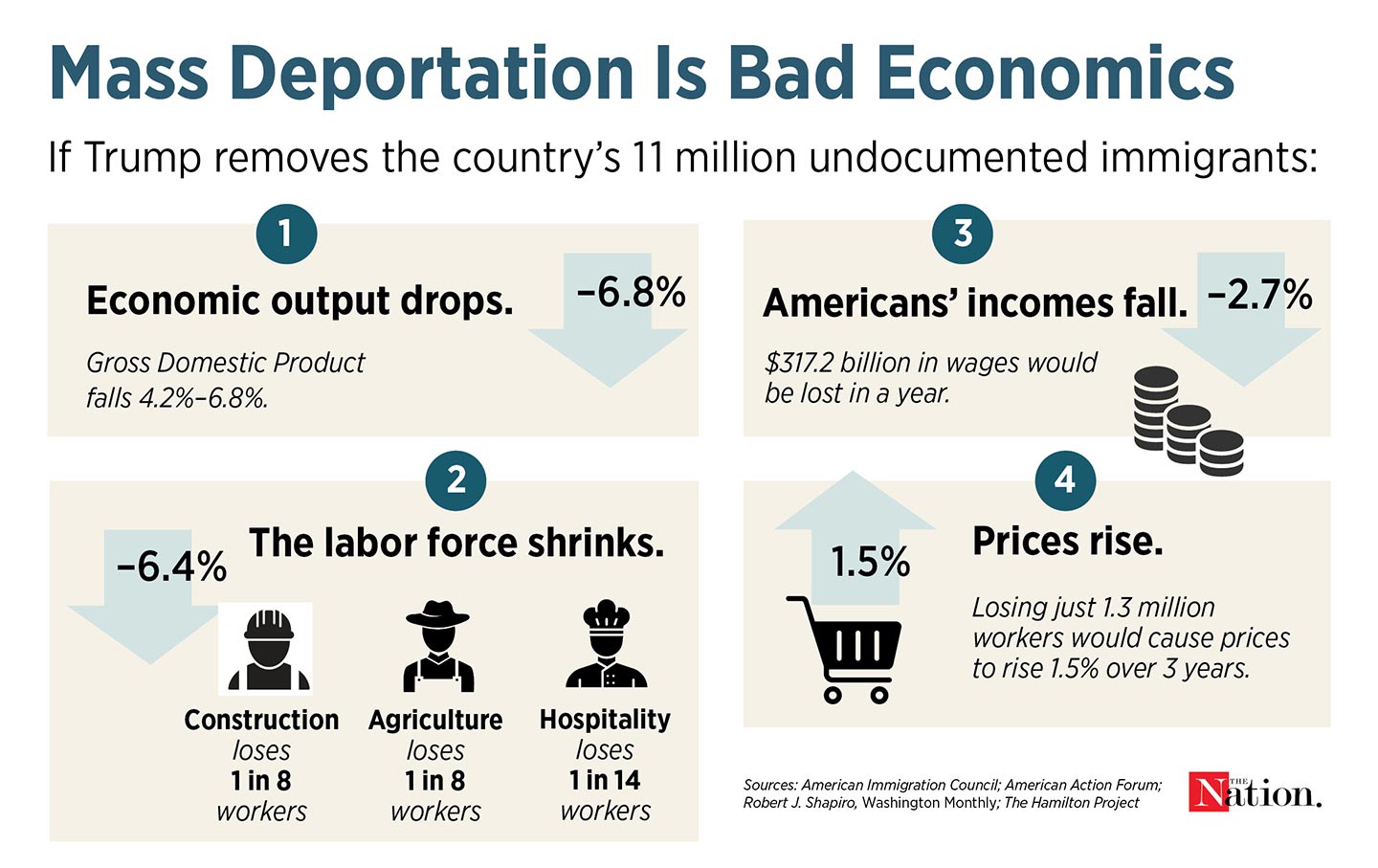

Mass Deportations Aren’t Just Evil. They’re Also Terrible Economics. Mass Deportations Aren’t Just Evil. They’re Also Terrible Economics.

Immigrants don’t steal citizens’ jobs and wages. They grow the economy for all.

Why Elon Musk and the GOP Have the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau in Their Crosshairs Why Elon Musk and the GOP Have the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau in Their Crosshairs

Republicans have long wanted to kill the CFPB. With Musk and Russell Vought, they may finally have their chance.