Biden Was Right to Block the US Steel Takeover

Even if losing domestic sources of primary steel does not seem like a national security threat today, it might tomorrow.

On Friday, President Joe Biden announced his decision to block the $14 billion acquisition of the US Steel company by Japan’s Nippon Steel Corporation. The move came seven months after Biden had told the United Steelworkers’ union (who opposed the merger) that US Steel should remain “domestically owned and operated.” More recently, the interagency Committee on Foreign Investment in the US, or CFIUS, which is tasked with reviewing cross-border mergers for their national security impact, was unable to agree on whether to recommend a green or red light. According to Bloomberg and The Washington Post, the US Trade Representative Katherine Tai, Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm, and Biden aides like Bruce Reed thought the risk was too great, while the Treasury, Defense, and State Departments thought the risks could be mitigated with tougher conditions on the sale.

Pundits’ reaction to the decision was largely negative. Libertarian think tanks and corporate groups bashed Biden, as did foreign policy mavens. One of the strongest condemnations came from Jason Furman, the head of the Council of Economic Advisers during the Obama administration, who called it “a pathetic and craven cave to special interests that will make America less prosperous and safe.” Among the few voices backing Biden, Senator Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) observed that “the deal was made behind closed doors without workers at the table.” Representative Ro Khanna (D-CA) argued that—were the tables turned—Japan wouldn’t allow a buyout of its national steel industry, while an adviser to Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) noted that the outgoing US Steel executive stood to receive a golden parachute of $72 million from the sale.

On Monday, as a snowstorm shut down Washington, DC, Nippon and US Steel filed a long-shot lawsuit in federal court to overturn Biden’s decision. While no court has ever overturned a CFIUS decision, the suit—along with a separate one against the head of the steelworkers’ union and a rival steelmaker—indicate just how fraught this late-Biden controversy has become.

Confused on what to think about all this? Was Biden’s blockage a corrupt giveaway to the unions? Or a display of pro-labor and industrial policy brilliance? Three questions determine where your answer falls.

Does it matter whether the US makes steel?

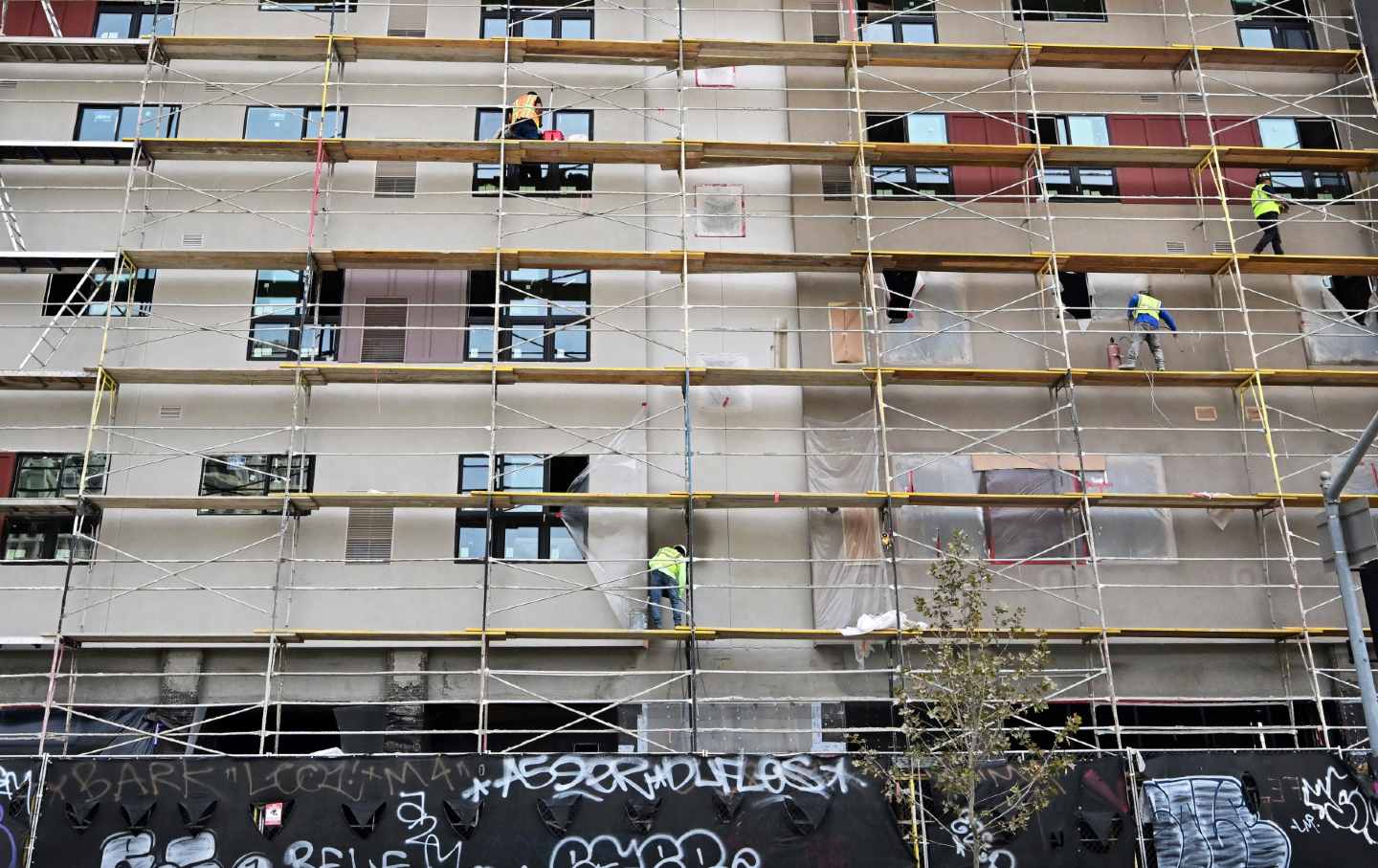

Steel is the most widely used metal in the world. It is a critical input from sectors ranging from buildings and infrastructure (the destination of 52 percent of all steel, where its non-combustibility helps protect homeowners from fires), to medical devices (where the same features allow them to be sanitized at high temperatures), to wind turbines (made up of over 80 percent steel). Without an adequate supply of fresh steel, numerous industries would be unable to produce the end products on which the rest of the economy relies. Past steel strikes and the Covid-19 pandemic offered a preview, when steel production dropped off, leading to bottlenecks in everything from auto production to farm equipment.

If the United States had hundreds of primary steel plants, then maybe it wouldn’t make sense to irritate an ally and block a foreign acquisition of any one of them. But today, there are just seven, three of which are owned by US Steel. Take even one of these facilities offline, and the domestic industry risks being permanently ceded to imports. (This is setting aside the still significant capacity the US has in so-called secondary steel, which recycles and thus is constrained by the availability of primary steel—a segment of the industry in which China dominates.)

Maybe your response to all this is to shrug. Most US workers have jobs in the service economy, and—even in manufacturing— many more workers are in steel-using than in steel-producing industries. Is it pure nostalgia or machismo to wish for a revival of American steel manufacturing? If foreign companies want to make all the steel for cheap and sell it to us, why shouldn’t we let the market figure this out?

The only problem: There is not—nor has there ever been—a free market in steel. Precisely because virtually all industries rely on steel, governments tend to intervene in the sector. There are sound economic reasons for this: The business is incredibly capital-intensive and has decades-long investment cycles. The US facilities, for instance, have blast furnaces that currently need to be replaced with expensive (but promising) zero-carbon technologies or relined to be able to function into the future, which could cost hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars. Not many private capitalists have that kind of money, which is just one of the reasons why steel tends toward oligopoly or even nationalized monopolies. Moreover, mills need to be run continuously to be profitable. That’s part of the reason the Trump administration imposed 25 percent tariffs on steel—it was a bid to restore the 80 percent-plus capacity utilization that is key to economic viability.

This gets at another point: In a crunch—be that wartime or economic shocks—steel companies tend to fall in line behind their home country governments. They sometimes put up a fight, as they did when the Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt administrations insisted they do their part for war mobilization efforts. But governments can use the threat of nationalization to bring companies into compliance.

This is where the government of Japan’s heavy lobbying for the deal may have backfired. During CFIUS deliberations as to whether Nippon would be more loyal to the Japanese state or its American operations, it was not a good look for diplomats to put their finger on the scale. The questions for the CFIUS were: In a global steel market plagued by overcapacity and Chinese dumping, what was to keep Nippon from cutting jobs in the US to preserve them back home? And why should the US government trust a company with a history of dumping products in the US market and that frequently sues the US for its actions to stabilize the domestic industry market? That was a consistent refrain from CFIUS and labor stakeholders, and one the company failed to persuasively address for more than a year. In short, even if losing domestic sources of primary steel does not seem like a national security threat today, it might tomorrow, when it would be too late to alter course. Once the know-how and skilled labor in the sector fades, it would be costly to recreate.

Does it matter how the US makes steel?

A lot of the coverage of Biden’s decision noted the lobbying efforts of labor and environmental groups. This created more public—and more political—attention than the normally staid CFIUS proceedings attract, and has generated a fair amount of anti-union commentary from Biden’s critics. It also elevated the debate to not just whether the US would continue to make steel, but how and under what conditions: unionized or deunionized? Would the steel industry be climate friendly or an environmental justice nightmare?

This civil-society interest should not be surprising. As Rana Foroohar of the Financial Times has reported, labor unions have an unusual degree of influence on the investment decisions of steel firms. The United Steelworkers’ contract with US Steel contains legally enforceable capital investments in domestic facilities, 60 days’ notice for major acquisitions, and “the earliest practicable notification” of buyout offers so that the union can organize a counterbid. In this case, Nippon announced the deal before consulting with the union. This pattern has been ongoing, with the company leaking union communications instead of waiting for their response, and US Steel making pledges via press release rather than through enforceable contractual commitments.

While much commentary on Biden’s decision noted the seemingly generous concessions that Nippon promised to make, the company included a so-called force-majeure clause that would allow these pledges to be clawed back if the company ended up having or picking fights with the labor union. The squishiness of Nippon’s commitments dates back to at least March. More recently, US Steel reportedly pressured local union workers to sign petitions in favor of the merger, while Governor Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania, who remained neutral on the deal, alluded to US Steel’s repeated threats against union workers.

At the same time, Nippon is a laggard when it comes to decarbonizing steel. In contrast, rival company Cleveland-Cliffs, which had organized its own bid for US Steel, is among the companies partnering with the US Department of Energy to make investments to improve air quality while preserving union jobs, including April’s announcement of a $500 million conversion project in Middletown, Ohio. Projects like this give the US a fighting chance to keep up with green steel leaders like Sweden. The Sierra Club, which has been working for years to decarbonize the steel sector, pointed out the Nippon tie up could have locked in emissions-intensive production. This is a big deal: Steel is on track to be one of the top emitting industries in the next decade, accounting for more carbon pollution than the entire European Union.

To be fair, labor and environmentalist interests are not 100 percent in sync. Scrap facilities are less carbon intensive (but largely nonunionized), while some union workers would probably be fine with relining existing facilities with older technology. The real question is: What strategy is more likely to balance the interests amid a disruptive energy transformation—one where government, business, workers, communities, and environmentalists are trying to navigate together? Or where these interests are pitted against one another?

Should the government have gotten involved?

Here is where it’s useful to read the laws, like the Defense Production Act that set up CFIUS. While the statute names may make it sound like policymakers would have to find a direct military threat from Japan or Nippon, that is not what Congress required or envisaged. Rather, the laws explicitly authorize policymakers to take into account a dozen considerations like the long-term health of the civilian economy, workforce, and energy security, and the effect an acquisition might have on critical sectors like steel. This puts the US president on par with foreign presidents and governments, who have extensive authorities to block takeovers.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In other words, there is not—and need not be—anything wrong with the US-Japan relationship in order for there to be CFIUS concerns. Indeed, the US is the number one destination for Japanese foreign direct investment by orders of magnitude, Japan is the top foreign investor in the United States, and Japanese clean energy companies are the top investors in US clean-energy manufacturing post-Inflation Reduction Act. In fact, Japanese companies and analysts see the Nippon block as a “one-off” and are expected to increase their investment in the US in the years to come. Nippon continues to run a number of secondary steel operations in the US. Mature, cooperative relationships like the US has with Japan are not broken by governments exercising their long-standing, normal merger review powers for sensitive sectors.

What comes next?

There’s still a nagging question: Even if the Nippon deal wasn’t perfect, was it better than nothing?

At one level, making this determination is not what CFIUS was tasked with doing. Rather, it was asked to consider whether there were national security risks to the transaction (in the broad sense that includes economic security), and if so, could those be mitigated? They could not uniformly conclude so, in part because Nippon’s incentives to stay committed to US Steel’s unionized primary workforce could change rapidly after the US government gives up its leverage or the next import shock from China or elsewhere. In that instance, we should expect Japan to (rightly) prioritize its own national interest.

That said, the path ahead is uncertain. One option is that US Steel continues to operate as a standalone company, though its eagerness to invest in nonunion facilities have exacerbated cash-flow problems. Another option is that US Steel’s rival Cleveland-Cliffs revives an earlier bid for the company. The US government’s subsidies, procurement, and infrastructure building are making US steel production more attractive, which could entice other buyers.

Nonetheless, what this episode shows is that corporate threats are not as effective as they once were. In the neoliberal era of years past, US Steel’s warnings of closure might have brought federal and local officials to heel. Today, however, there is a bipartisan consensus in favor of maintaining a domestic steel industry. There is little doubt that, if US Steel’s mills falter, the government will ensure that they survive, whether that be with tariffs, bailouts, or even partial or full public ownership. The latter, while it may seem like a remote possibility today, may be unavoidable in a true crisis. (Think Obama’s bailouts of AIG and the auto industry bailouts in his first term.)

The real questions, in the end, were whether taxpayers are more likely to support subsidies (which most experts agree will be necessary to address Chinese competition and climate change) for a domestic or foreign firm and whom to trust more: C-suites with their golden parachutes, or unions who have an interest in seeing the steel industry survive? Far from putting political gain above substantive concerns, Biden’s decision is a case where the substantive concerns were serious enough that they merit the political and legal costs that blocking the acquisition are already incurring at home and abroad.