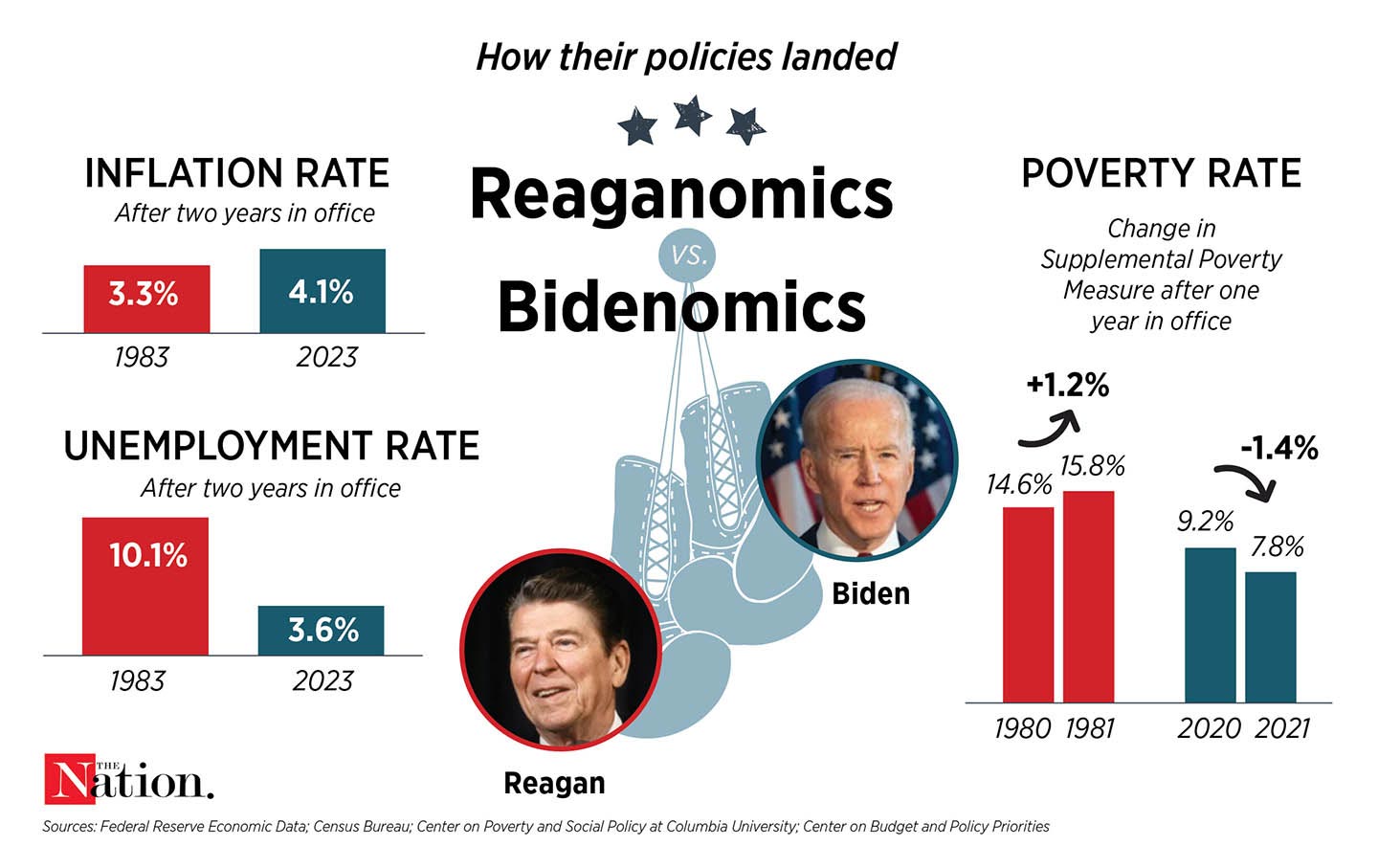

In a June 28 speech, President Joe Biden embraced the term “Bidenomics” and described it as encompassing “three fundamental changes” to economic policy. He said his administration was “making smart investments in America,” “educating and empowering American workers to grow the middle class,” and “promoting competition to lower costs to help small businesses.” Given the fact that Biden is using this framework to sell his accomplishments to voters ahead of the 2024 election, it’s worth comparing it to a similar term that emerged during a very different presidency: “Reaganomics.”

In 1981, within months of Ronald Reagan moving into the White House, people started debating what Reaganomics would accomplish. Reaganomics—like Bidenomics—rejected the previous era’s economic orthodoxy. Both economic agendas proposed new theories of how to expand the supply side of the economy and reimagine the role of competition. For Bidenomics to succeed, it needs to carry out the two projects as thoroughly as Reaganomics did.

Reaganomics and Bidenomics both jettisoned the dominant economic assumptions that had been held by both parties. Reaganomics abandoned Keynesian liberalism, and while it’s not a central part of Biden’s economic messaging, Bidenomics is a repudiation of the market-centric globalization of the past 30 years.

In April, Biden’s national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, argued that there was “a new consensus” for “pursuing a modern industrial and innovation strategy—both at home and with partners around the world.” Like Reagan’s rejection of Keynesianism, this reflects immediate political priorities as well as changing opinion. Academics and policymakers are finally coming around to the idea that unfettered global trade hasn’t created a harmonious, peaceful, democratic global order. Instead, it has made us vulnerable to weak supply chains, created national security concerns, and pushed large swaths of the country into poverty and economic isolation. Bidenomics, in contrast, takes a more affirmative stance toward economic development by driving investment to green energy and manufacturing.

Both Reaganomics and Bidenomics also represent shifts in the way the government treats the supply side of the economy. The supply-siders in the early Reagan administration focused on reducing corporate and marginal tax rates. In contrast, over the past few years the “supply-side progressives” in Biden’s administration have emphasized the government’s role in investment, worker protections, and building out the care economy. As Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said in January 2022, modern supply-side economics “prioritizes labor supply, human capital, public infrastructure, R&D, and investments in a sustainable environment.”

Finally, both Reaganomics and Bidenomics contain theories about how best to promote competition. Reagan brought with him a decade of regulatory policy innovation created in conservative law schools and economics departments. He took a hands-off approach to competition, assuming that markets alone would ensure it and give consumers the best deals. Similarly, the Biden administration brought with it a decade of analysis on what’s gone wrong with the growth of corporate power. Here the president’s achievements have already piled up. Under Biden, the government has proposed a ban on many types of noncompete agreements, intervened to reduce prescription drug prices, and taken a more skeptical approach to mergers.

There are additional similarities. Historians see President Jimmy Carter as having begun to implement some of the changes that Reagan would formalize, and so too might historians come to view Donald Trump’s fumbling trade policies as awkward attempts at what Biden has done properly.

It remains unclear whether Bidenomics will define the political landscape the way Reaganomics did. Under Reaganomics, the sharp drop in tax rates supercharged inequality to levels that hadn’t been seen in 50 years, giving the rich more power to rewrite the economic rules. Under Biden, the Inflation Reduction Act is transforming American industry, but it’s uncertain whether the IRA can create a self-sustaining momentum for a progressive agenda. It is also always easier to tear down than to build up. Reaganomics was about destroying the state’s ability to act and turning that power over to corporations and the wealthy. The question now is: Will Bidenomics help us build something new in its place?

Mike KonczalTwitterMike Konczal is a contributor to The Nation and a director at the Roosevelt Institute, where he focuses on inequality, unemployment, and new economic ideas. He is author of Freedom from the Market: America’s Fight to Liberate Itself from the Grip of the Invisible Hand (The New Press).