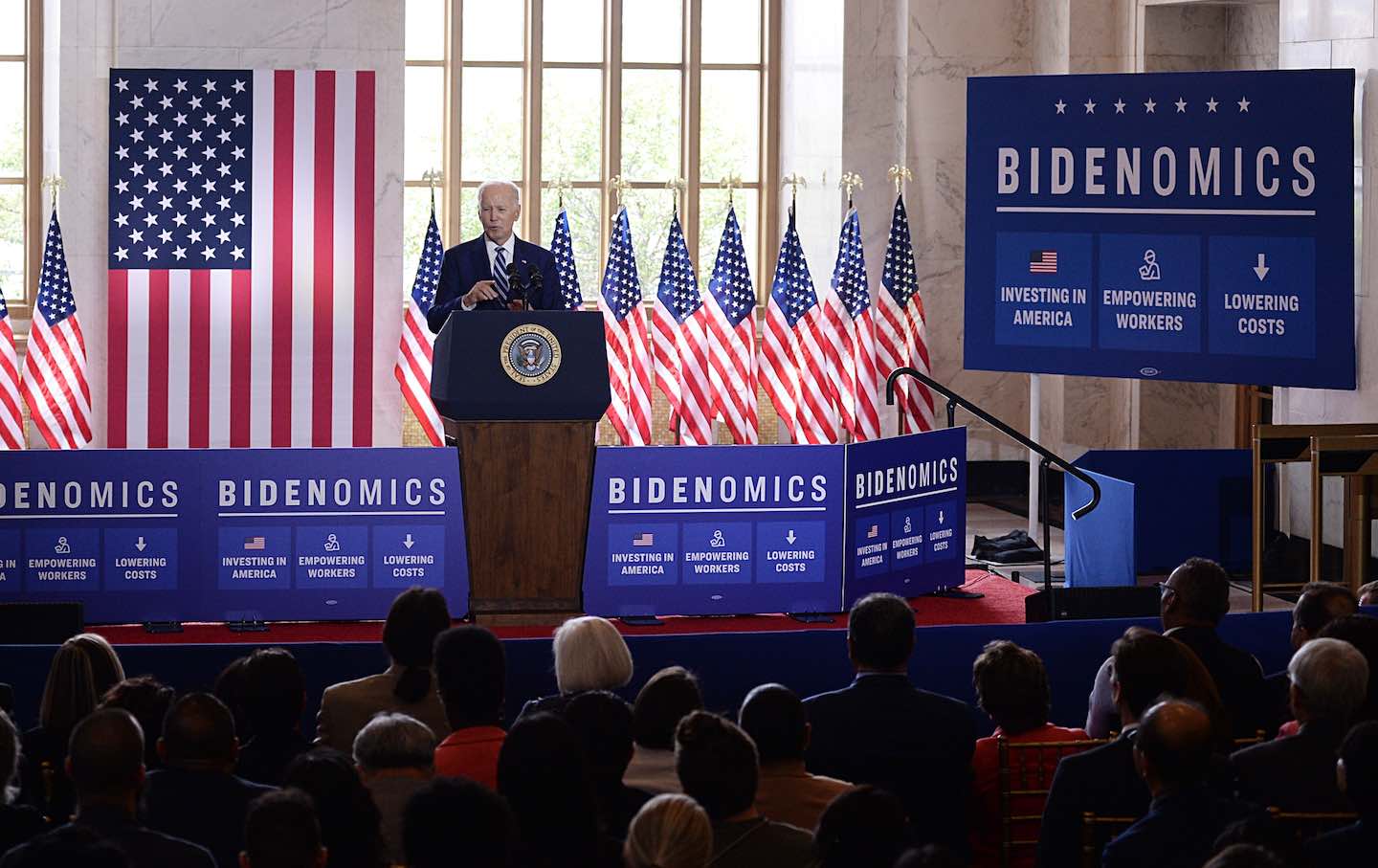

President Joe Biden speaks about his economic plan, “Bidenomics,” at the Old Post Office in Chicago, Ill., on June 28, 2023.(Jacek Boczarski / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

This Wednesday, President Joe Biden showcased what’s sure to be a central theme in his reelection campaign with a speech in downtown Chicago hailing the signal achievements of his economic agenda and firmly repudiating the legacies of trickle-down economics. Speaking before a crowd of local and statewide political and business leaders at the city’s Old Post Office building, Biden announced his determination to ensure that the US economy grow “from the middle out and the bottom up rather than just top down”—an approach that marks “a fundamental break from the economic theory that’s failed America’s middle class for decades now.”

It’s true, as Biden went on to argue, that American prosperity is, by any number of metrics, on a more solid and equitable footing than it has been for many years. Unemployment remains below 4 percent, and the administration has added more than 150,000 jobs over the past 28 months, for a total of more than 13 million—a record among presidents, even factoring in the acute loss of jobs over the Covid recession. Inflation is down more to less than half of its 9 percent high last June, at just over 4 percent. Major outlays for infrastructure and climate mitigation have helped create new markets for tech innovation and have stabilized private investment.

So what’s wrong with this picture? Why do even many Democrats say they’re underwhelmed by Biden’s leadership on economic issues? And how can the top-line indicators of economic well-being translate into a winning message in the upcoming election cycle?

Biden’s talk sought to stake out key answers to these quandaries by embracing a phrase initially floated by an economist in The Wall Street Journal as an intended term of derision: Bidenomics (it being a generally sound principle that a Journal-branded form of calumny is definitionally misguided). In Biden’s telling, his vision for robust and fairly distributed economic growth hinges on bold public investments—such as those endorsed in the infrastructure law and the Inflation Reduction Act—and gains momentum from pro-worker and Buy American policies, while also ensuring fair competition via antitrust enforcement and small-business creation. Repeating a favored applause line, he announced, “I meant what I said when I said I was going to be the most pro-union president in American history, and I make no apologies for it.”

But this is precisely where the picture gets hazy. In touting his fiscal discipline, Biden hurriedly took credit for $1 trillion in deficit cuts ratified under the debt-ceiling agreement he struck with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, “without giving anything of consequence.” But that deal is poised to beggar some 40 million holders of educational debt, if the Supreme Court proceeds to wipe out Biden’s own student debt-relief plan. (For D.C. policy hands prone to shrug off that betrayal as a savvy choice to drop another dubious middle-class entitlement, that’s simply not the case, as Biden declared elsewhere in his speech, when he pledged to anchor broad-based social mobility in free community college.) Biden also notoriously bigfooted a threatened rail workers’ strike last winter, and has lent little assistance to a desperately underfunded National Labor Relations Board. It’s a decidedly equivocal track record for the country’s most pro-union president—and will likely complicate his election-year efforts to depict himself as the second coming of FDR.

Another fierce complicating factor is Biden’s decision to retain Jerome Powell, the Trump-appointed head of the Federal Reserve. Powell is a dogmatic inflation hawk who’s pushed a long run of interest rate hikes to slow wage growth, which he (mistakenly) diagnosed as a key accelerant of inflation. (The specter of “greedflation”—i.e., opportunistic corporate price hikes engineered to pad private-sector bottom lines—was widely dismissed by the mainstream press and economic savants, but now seems to be a much more likely culprit.) Powell has at last inaugurated a pause in his rate-hike strategy, but he continues to preach an absurd austerity gospel under conditions of near-full employment and receding inflation. Even as Biden was preparing to deliver his Chicago speech, Powell was back on his doomsaying beat, announcing that a recession remained a “significant probability,” even if he also somewhat grudgingly conceded that it’s “not the most likely case.”

Biden’s other problem is that the mainstream media laps up such hawkish fiscal rhetoric with relish. Inflation-taming is the only narrative about the American political economy that can be relied on to stoke visceral alarm in viewers and readers, so media producers recur to it obsessively. “The media have been playing up the negatives every step of the way,” says Dean Baker, senior economist and cofounder of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. “In addition to inflation, they’ve been talking about labor shortages, but I say, ‘Well, what’s that mean? It means that workers can negotiate better in a tight labor market.’ Wages had arguably been growing rapidly at the start of 2022, but they’ve slowed hugely. That’s not questionable—we have data on that. So in dealing with the Fed, are they saying with wage growth down to 4 percent now, that’s inconsistent with their inflation targets? You’re telling me we’re going to risk a recession to slow inflation rates? That’s close to crazy.”

It’s also glaringly out of touch with reality. “If you look at what the big risk to the economy is, all the indicators are trending well,” Baker notes, “Housing looks good; durable goods, nonresidential construction are doing well; even trade deficits are getting smaller. None of this is going in a recessionary direction, so what would be the story where we get a recession or a bad economy? It would likely be the high interest rates…. That could give you a serious slowing.”

But as far as mainstream economic and media discourse are concerned, the threat remains firmly fixed: Inflation must be tamed into extinction, by any means necessary. As a result, news outlets flogging this narrative “basically lie,” Baker notes. “In talking about housing prices, the press had a number of stories that said low-income people, young people, and Black Americans are finding it harder to buy homes. Well, for all these groups, home ownership is up over pre-pandemic levels—literally the opposite of what they were telling people.”

This stolidly fact-averse discourse is also what allowed the delusional portrait of Donald Trump, economic populist, to take hold; that, too, is largely a work of feverish projection on the part of a political press easily bewildered by developments outside the Fed-modulated paper economy. To dislodge this narrative template, Biden and his economics team will likely have to move beyond a political rhetoric of reassurance and reasoned compromise. It may require the revival of something like FDR’s freedom from want as a universal social good—which is to say, bringing a lot more of the bottom-up agenda to the present middle-out status quo.

Chris LehmannTwitterChris Lehmann is the DC Bureau chief for The Nation and a contributing editor at The Baffler. He was formerly editor of The Baffler and The New Republic, and is the author, most recently, of The Money Cult: Capitalism, Christianity, and the Unmaking of the American Dream (Melville House, 2016).