In the wake of the Covid recession, state and local governments have the chance to remake local labor markets—and public assistance—by adopting a policy guaranteeing half-time employment at $15 an hour for every resident.

Despite the hype of supposed proliferating job openings, long experience shows that even if we approach rates of nominal “full employment” again, such statistics will inevitably ignore higher unemployment rates for Black, Latino, formerly incarcerated, and many other workers. In a Covid-based recession where women in particular have struggled to return to previous levels of employment, a job guarantee may be critical to restore real employment alternatives for everyone who wants a job.

So why only a half-time job guarantee?

Because any state or local government will inevitably struggle with the costs of launching such a program, guaranteeing half-time jobs will be far more economically feasible. And because of the perversity of welfare benefit phaseouts, a half-time work guarantee will deliver much of the income of full-time employment, particularly for parents with kids. As importantly, a half-time program addresses some of the political and social challenges even progressive critics of job guarantees highlight, since it would give recipients time to care for their children, pursue education, or seek additional part-time work in fields where they eventually want to gain full-time, better-paying permanent employment.

Such local job guarantee programs would build on federal proposals in recent years by Bernie Sanders, Cory Booker, proponents of the Green New Deal, and policy centers like the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the Center for American Progress, and the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College—all pushing federal programs to ensure that anyone wanting a job is guaranteed one by the government.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →While no federal job guarantee program looks likely to be approved in the current congressional session, the federal dollars flowing to states and local governments from the American Rescue Plan Act and Biden’s projected “Build Back Better” program create an opportunity for some states and local governments to pilot local versions that could be models for a future federal policy.

Such federal funding will help offset the substantial initial costs of a job guarantee program—which in time, as multiple studies of job investment programs show, will substantially offset those initial costs. By raising the long-term income of participants, a job guarantee will stimulate the overall economy and increases local tax revenues. Higher job participation also tends to reduce other government spending, by improving school outcomes of participants’ children and reducing criminal justice costs.

Beyond supporting participants themselves, a key goal of a job guarantee is to expand overall worker power in the economy to demand higher wages. Reducing the desperation of the unemployed will strengthen individual and collective bargaining in all local industries; the resulting higher wages and consumption in turn will stimulate local economies and tax revenue.

But can workers and their families thrive on a half-time job guarantee?

Obviously, income from half-time work even at $15 per hour is not going to be a comfortable life, but because government supports have become more generous—particularly with policy changes made during the pandemic—a half-time job guarantee offers a reasonable safety net for working families.

Notably, Biden policies making the Child Tax Credit larger and refundable, expanding SNAP nutrition benefits, and enlarging the EITC for childless workers all help make half-time job guarantees more viable.

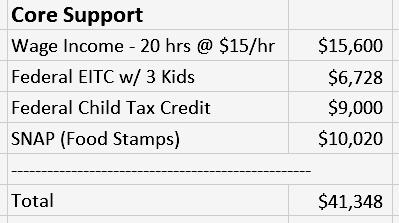

To put numbers on this, half-time work at $15/hr pays $15,060 per year. For a single parent with three kids, that will be supplemented by a $9,000 child tax credit (up to $10,800 if the kids are 5 or under), a $6,728 EITC payment and up to the maximum $10,020 yearly SNAP allotment, yielding a base of roughly $41,000 in annual income.

That can be further supplemented by child care tax credits (as much as an $8,000 credit at least temporarily under the American Rescue Plan), state supplements to the CTC and EITC (roughly $3,000 in New York City, for example), rental housing subsidies (substantial in amount but with limited availability), heating and other utility subsidies, as well as other supports such as discounted transit. Families and individuals at this income level also qualify for Medicaid, eliminating most health care costs as well.

Not a luxurious standard of living, to be sure, but these numbers emphasize that, program-by-program, progressives have made significant strides in making the lives of the working poor far better. A half-time job guarantee builds on these previous policy victories.

Perversely, as family incomes rise much above $20K per year, many of these financial supports begin to phase out, partly and at times completely offsetting any income gains. As the Congressional Budget Office found in one analysis, marginal tax rates can approach 100 percent for many low-income families. The Urban Institute has similarly found that additional wage earnings for working poor families can lead to little net gain in overall income.

That’s why aiming for a half-time job guarantee makes sense. The goal should be to treat such jobs as a safety net where workers are supported in eventually finding full-time work that provides not just more hours but substantially more hourly pay, delivering a real jump in family income.

Ensuring that these half-time jobs remain clearly distinct from permanent public employment will also reduce tensions with public employee unions. And instead of “stranding” participants in work they don’t like—as some critics of full-time job guarantees worry—people in half-time jobs will still be able to pursue educational, volunteer, or other part-time opportunities that can lead to better-paying careers. The point, as Pavlina R. Tcherneva of the Levy Economics Institute argues, is for a job guarantee to act as a transitional program, “a stepping stone…to other forms of private, public and nonprofit employment.”

However, it’s also worth asking whether the 20-hour work week for such guaranteed jobs shouldn’t be a longer-term goal for all of society. Economist Hyman Minsky, a seminal original proponent of job guarantees in the post–World War II period, envisioned at one point making the four-hour day the standard for all work. While some people might seek additional income by combining two such jobs, Minsky argued that a single job should be designed to suffice so that older adults or those with child care responsibilities could live full lives on such income. We have long been locked into the paradigm of the 40-hour work week—a great social accomplishment a century ago—but should use the job guarantee program to begin moving toward a new framework for work.

One political advantage of the job guarantee is that it links the income of all lower-wage workers together via the minimum wage, so efforts to raise wages for full-time workers would also help those on the job guarantee program—and increasingly make the 20-hour work week an attractive option, especially if we continue to strengthen associated income supports as well.

This shared fate for all low-income families via the minimum wage is also a prime reason the job guarantee is a better policy to pursue than Universal Basic Income (UBI) approaches.

We have repeatedly seen how conservatives politically divide workers from those who are unemployed and survive purely on government-based income. Those on Pandemic Unemployment Insurance were dismissed as undermining the recovery and being just plain “lazy”—leading Joe Manchin and others in Congress to unceremoniously kill the whole program as of Labor Day. Manchin just this week complained that the refundable Child Tax Credit should be linked to work requirements, also highlighting the continual political peril of any UBI-like program. Income programs supporting workers, on the other hand, are quite popular, so a job guarantee policy may help cement the income support programs that make it viable.

Multiple polls show solid majorities supporting job guarantees, while few find any deep support for UBI. One poll by Indeed found 56 percent support for a job guarantee but only 28 percent for UBI. Polls by Civic Analytics and by Data for Progress reported similar or greater levels of support for a job guarantee—finding particular support for it among lower-income Republicans, emphasizing the potential bipartisan base for maintaining the program over time.

It’s notable that the largest existing job guarantee program in the world in India is itself a part-time guarantee, offering 100 days a year of work to the rural poor. Despite professed hostility by the current BJP government, that program—enacted by the Congress Party a decade ago—has survived and grown because of its popularity. In 2020, it provided work to an astounding 90 million rural Indians, playing a key role in stabilizing the economy in the face of the pandemic, and polls show 82 percent of city residents now want the program extended to the urban poor.

A half-time job guarantee program will be an incredibly heavy budgetary lift for any state or local government, but the economic and political gains from it will multiply over the years. Building on existing victories providing income support for low-income work, it could even create a new paradigm of a four-hour workday as the building block for our economy.