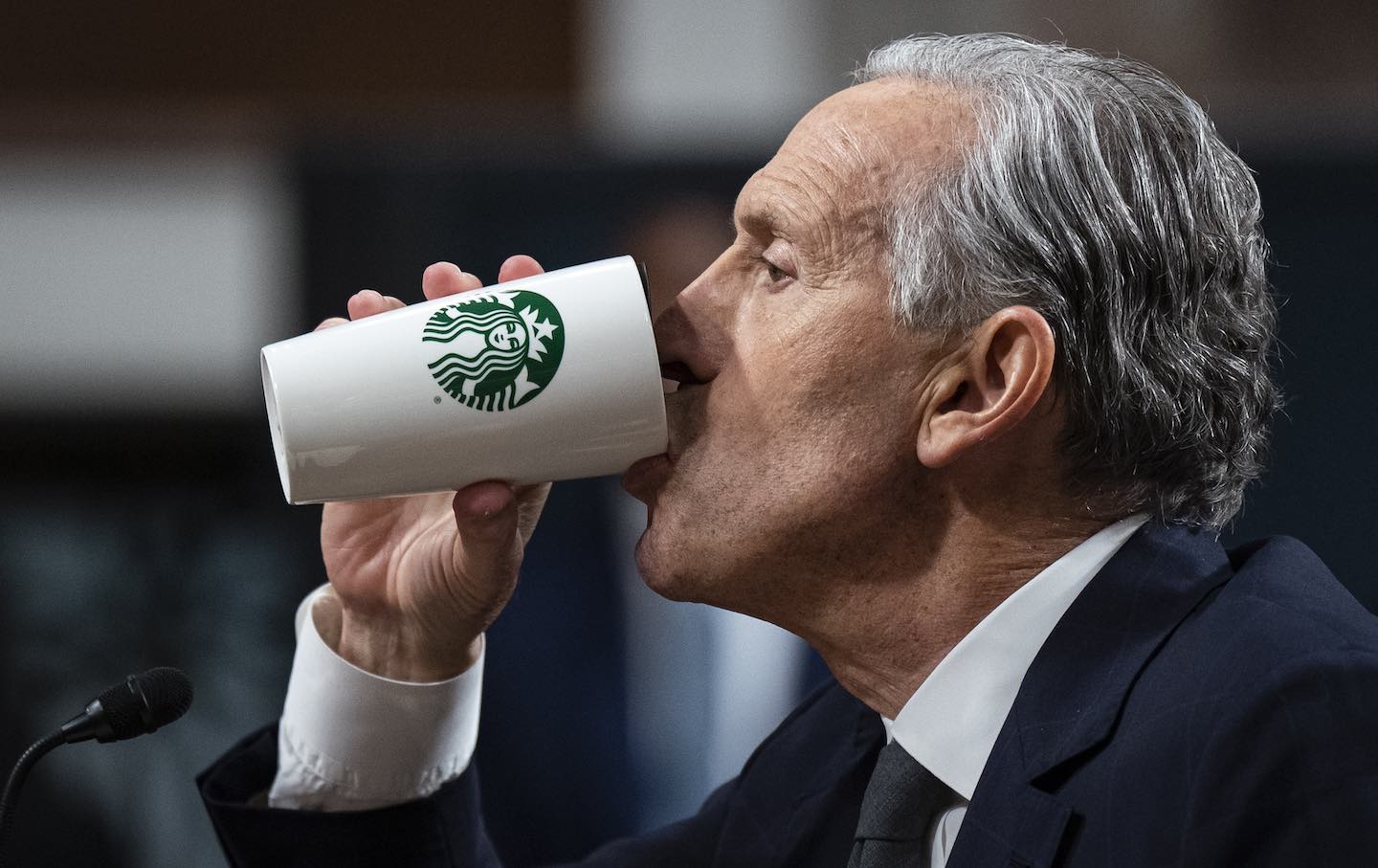

Howard Schultz, former chief executive officer of Starbucks Corp., drinks from a Starbucks mug during a Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee hearing in Washington, D.C., on Wednesday, March 29, 2023.(Al Drago / Bloomberg)

Former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz, briefly touted as a dark-horse Democratic candidate for the presidency in 2020, found himself at a less obliging juncture of federal power this Wednesday, as he delivered testimony on the coffee giant’s union-busting track record before the US Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) Committee. Members of the Starbucks Union thronged the corridors outside the Dirksen Building hearing room, anticipating that the company might finally be held to public account, and be shamed into launching good-faith negotiations for a collective-bargaining agreement. Organizers greeted one another with loud and cheerful “good mornings,” seemingly out of professional habit, but the real message for the occasion was emblazoned on the backs of their T-shirts: “Partners? Prove It—We ARE Starbucks.”

Schultz, who returned to the top post at Starbucks in August 2021 and wound up his second CEO tour last week, proudly calls all employees of the chain “partners,” but the company’s HR rhetoric of equitable collaboration has frayed over the course of a historic organizing drive among Starbucks workers. Some measure of the hostile state of employee relations came across in the circumstances of Schultz’s appearance. He was testifying under subpoena, after several months of resisting invitations from the HELP committee. And from the moment he began speaking, he kept up a stout litany of lawyer-vetted denials of wrongdoing before the committee. He only seemed poised to lose this unflappable mien a few times—chiefly when the chair of the panel, independent Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, pressed him on the company’s repeated violations of labor law and ongoing failure to negotiate a collective bargaining agreement with Starbucks employees more than a year after workers at a Buffalo, N.Y., location first voted to form a union in 2021.

Schultz’s mantra before the committee was that neither he nor the Starbucks corporation were in violation of any law, even though the coffee chain has racked up more than 500 NLRB complaints alleging labor violations across 38 states, as Sanders noted in his opening statement. One NLRB judge in the Buffalo case cited the company for “egregious violations” and “widespread coercive behavior” on the part of company brass looking to retaliate against pro-union workers there in order to prevent the present wave of Starbucks union drives from taking off. Schultz repeated this rote denial of any illegal conduct on the part of himself and his company so regularly that an exasperated Chris Murphy, Democratic senator from Connecticut, asked Schultz, “What do you mean when you say you abide by the law?” Murphy went on to observe that the rote denial of such a vast body of complaints was “akin to someone who’s been ticketed for speeding more than 100 times saying that every single time the cops got it wrong.” Schultz wanly kept insisting that “what you’re talking about is allegations…. I believe the allegations will prove that Starbucks is correct.”

Schutlz’s testimony, then, was an extended study in managerial messaging, built on the story of his own hardscrabble upbringing and ascension through the ranks of entrepreneurial innovation. The end result, Schultz claimed, was an enlightened “vision” of Starbucks’ corps of “partners” who maintain fierce loyalty to the corporate culture and brand of Starbucks. In return for this devotion, he explained, Starbucks has paid workers well above the minimum wage in all states, and has pioneered generous profit-sharing deals and full undergraduate college tuition subsidies for qualified workers.

Another term for this vision is “paternalism”—the long-standing management strategy of buying off worker solidarity on the job so as to make unionizing seem pre-emptively costly to workers. This faux-solicitude for “the 250,000 workers who wear the green apron,” as Schultz put it, sits awkwardly aside the well-documented picture of a company that hires notorious union-busting consultants, deliberately slow-walks contract negotiations in a high-turnover industry to wear down its union-supporting opponents, and seizes on the rulings of right-wing federal jurists to institute a regime of wide-ranging surveillance. This full-court press to stamp out all pro-union activity throughout the Starbucks empire is also what permits Schultz to disingenuously claim that the company’s cohort of organizers is a pesky and unrepresentative dissident faction, out of line with the “99 percent” of contented partners who “want a direct relationship with the company.” What that 99 percent more likely want is simply the ability to retain their jobs in the face of a retaliation-minded management regime.

Democratic interlocutors on the panel called out the vast gulfs of economic agency concealed by the serene surface of Schultz’s managementspeak. Minnesota Senator Tina Smith asked Schultz “You call your employees partners, but do you value those who want to join unions?” Wisconsin Senator Tammy Baldwin pointed out, “There’s a power differential here—a power you’ve shown your willingness to wield. I find it particularly ironic that you don’t see this power dynamic. You can’t possibly have a direct relationship with all your workers—but if you really want a direct relationship with your employees, a union could provide this.” Smith cited the company’s retaliatory practices against pro-union workers, such as denying them credit card tips at a per-worker pay loss of approximately $4 per hour, and the denial of the most recent of company benefits to pro-union workers on the flimsy rationale that federal law allegedly forbids the “unilateral” extension of such benefits to workers in the midst of contract negotiations. When Smith pointed out that the Starbucks employees in question had waived any objections to this procedural obstacle on the union side, Schultz returned to his core waspish talking point: “It is our preference and our right to negotiate that contract, but not in piecemeal fashion.” Revealingly, talk of the limits imposed by labor law was suddenly suspended; all that was left, yet again, was management prerogative.

Other exchanges highlighted similar cracks in the paternalist veneer of Starbucks. At one point, when Schultz was pressed to explain a hastily convened 2021 executive summit with the Buffalo area workforce that stressed the downsides of union membership, he replied that he never mentioned the word “union” at all in his presentation—that he was only there to explain the company’s mission to a Starbucks workforce whose tenure at the company was less than a year, and so weren’t adequately schooled in the attractive features of their enlightened partnerships. Schutlz claimed that, under the pressures of the pandemic, fully 95 percent of the company’s workforce had come on board inside of a year; elsewhere in his testimony, he boasted that the company retained its workers at twice the prevailing rate of the industry, something that his own math renders a clear impossibility. (This is all to say nothing, of course, of the obvious question of why Buffalo in particular needed so urgently to serve as the site of this particular refresher course in managerial paternalism.)

The panel’s Republican members, not surprisingly, saw nothing untoward in any of this. Utah Senator Mitt Romney—the Bain Capital job killer who sank his own presidential campaign with the for-donors-only message that 47 percent of the electorate languished on the federal dole and were in cahoots with Democratic barons of entitlement to secure more of the same—cooed to Schultz that “it’s somewhat rich that you’re being grilled by people who’ve never created a single job.” This was a brute reminder that Romney, something of a mascot for the beleaguered Never Trump right, has always been a thug in matters of political economy, infamously calling for the auto industry to be euthanized in the wake of the 2008 economic meltdown.

Indeed, the bartender who was working at the Romney donor confab and taped the candidate’s remarks explained that Romney’s “47 percent” line hadn’t been his most objectionable utterance at the event; instead, it was a plainly apocryphal managerial fable about Chinese labor compounds erecting high fences at their perimeters—not, you understand, to prevent exploited workers from escaping, but to keep eager-to-be-sweated laborers from burrowing in. In other words, any time Mitt Romney starts sermonizing on labor relations, it’s time to cue up the IWW anthems. Kentucky’s Rand Paul, hilariously, invoked sociopathic Ayn Rand hero Howard Roark in the opening sentence of his remarks, which went rapidly downhill from there. Louisiana Senator Bill Cassidy, meanwhile, used a recently filed whistleblower complaint against the NLRB to intimate that the whole agency is just another tentacle of the deep state, driven by an agenda of raw political retribution.

Several of Schultz’s Republican backers paused to note the ostensible irony of their rallying to the defense of a putative liberal Democrat. But irony is about unintended consequences, and the shared intent of the Romney and Schultz class is all too plain, and untroubled by any deep underlying ideological tensions. It is, indeed, the only partnership that matters here.

Chris LehmannTwitterChris Lehmann is the DC Bureau chief for The Nation and a contributing editor at The Baffler. He was formerly editor of The Baffler and The New Republic, and is the author, most recently, of The Money Cult: Capitalism, Christianity, and the Unmaking of the American Dream (Melville House, 2016).