Should the Government Break Up Big Corporations or Buy Them?

Matt Bruenig writes that governments should nationalize more companies while Zephyr Teachout argues that freedom requires decentralized power.

Buy Them!

When the Tennessee Valley Authority outsourced 146 jobs in 2020, the unions representing the affected workers blasted the decision and asked federal lawmakers to intervene. President Donald Trump responded by removing two of the TVA’s board members and criticizing the CEO. Three days after Trump got involved, the TVA rehired the workers it had just laid off.

The TVA is an electric utility company that serves 10 million customers in the southeastern United States. It operates as a giant monopoly. In most circumstances, this would make it an agent of “corporate power” that the government tries, mostly in vain, to rein in. But unlike normal companies, the TVA is owned by the federal government. Thus when the government wants the TVA to behave a certain way, it doesn’t have to break it up, initiate an administrative proceeding, or construct some sort of regulation. Instead, it can exercise its ownership rights, as Trump did, to steer the company in whatever direction it likes.

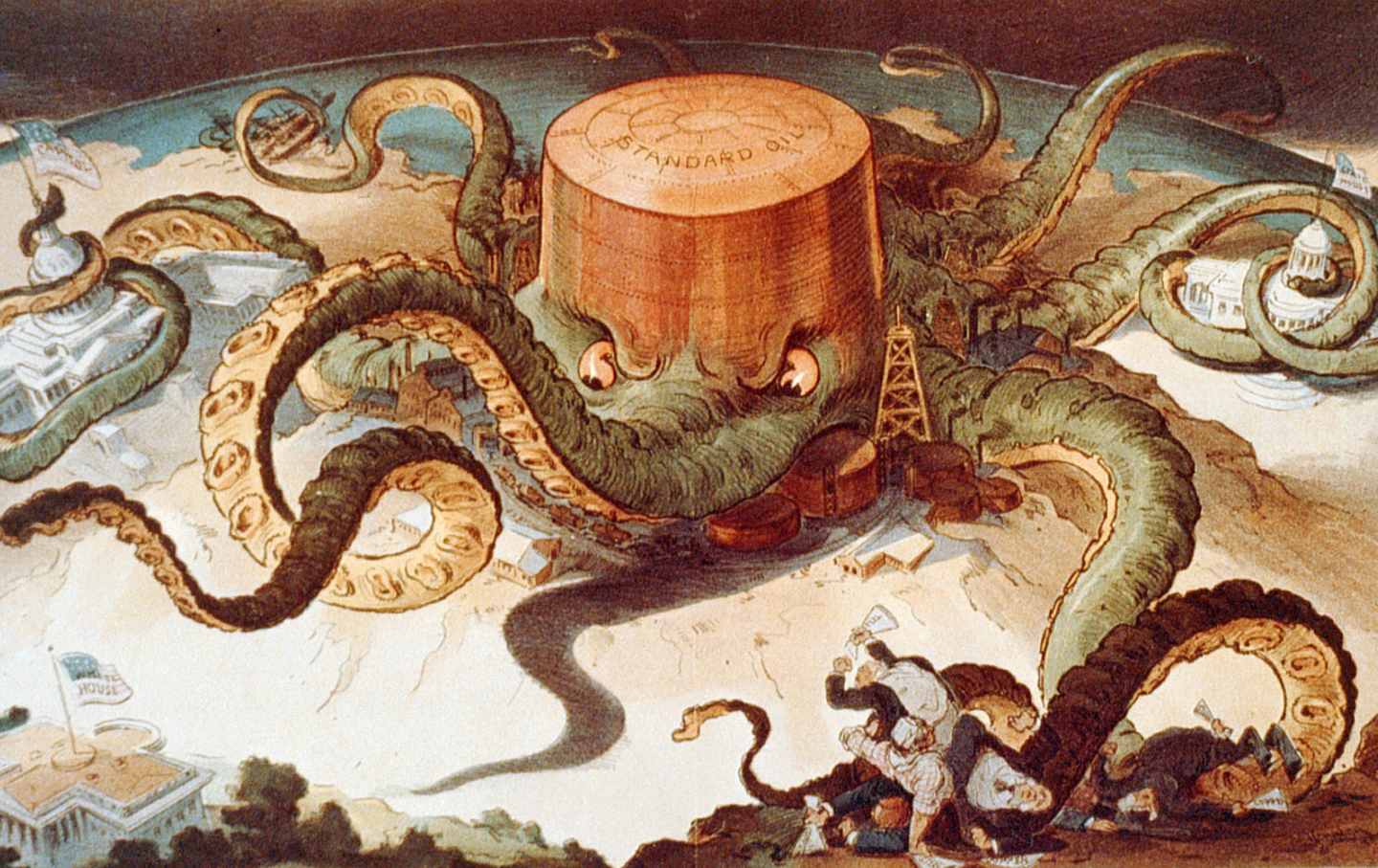

In recent years, there has been a resurgent anti-bigness movement on the American left, with more and more people claiming that the central problem with our economy is not that it is too capitalistic, that it lacks unions, or that it offers too little security in the form of the welfare state. Rather, according to anti-bigness campaigners, the economic problem of our time is that production is spread out across too few firms.

I don’t think this is the correct diagnosis. I believe that rather than attempt to indirectly alter a company’s behavior by trying to construct some kind of perfectly balanced market of private competitors, the government should, in most cases, just buy the company, keep its productive capacity intact, and then use its ownership rights to change its behaviors.

In 2022, for example, the anti-bigness movement got the Biden administration to take on the meatpacking sector on the basis that it is dominated by four large companies and that those companies therefore have significant pricing power upstream with ranchers and downstream with wholesalers. The Biden administration’s plan was to break up this concentrated sector by providing $1 billion to smaller competitors to take market share from the big guys.

A much better approach would be to simply purchase one of the big four meatpacking companies and run it as a federally owned enterprise like the TVA. The publicly traded Tyson Foods has a market capitalization of less than $25 billion. For that relatively small sum, which would not be lost to the federal government but rather invested in Tyson stock, the government could instantly direct one of the biggest meatpacking companies to stop using its market power to squeeze ranchers and customers. This, in turn, would force the other meat-packers to do the same or risk losing share to the now federally owned Tyson Foods.

More recently, Kamala Harris accused big grocery chains of using their market power to jack up prices on consumers and vowed to fight concentration in the grocery sector as president. Instead of doing this, it would be easier and more effective for the government to buy the second-largest grocery store chain in the country, Kroger, which has a current market capitalization of about $38 billion. If Kroger and its peers really are engaged in price gouging, as Harris claims, then this could be stopped immediately if Kroger were publicly owned.

Using selective public ownership in this way may seem like a radical proposition, but there is a precedent for it in the United States. The country’s postal logistics sector is dominated by three firms: UPS, FedEx, and the US Postal Service. If these were all private companies, the anti-bigness campaigners would surely be calling for them to be broken up. But because one of these companies—the USPS—is owned by the federal government and operates in a break-even manner, it’s not necessary. Whatever market power UPS and FedEx have is largely checked by the fact that customers can always turn to the USPS, which does not pursue the same kind of profit-maximizing pricing strategies as the other two.

In addition to directly changing the behavior of specific companies and indirectly changing the behavior of their competitors, this public ownership approach might also chill predatory behavior across sectors that do not wish to find themselves the next target for nationalization.

Most anti-bigness advocates will not find this approach satisfactory, in part because they have certain goals that the public ownership of large enterprises does not accomplish. For instance, the foundational texts of the modern anti-bigness movement often argue that we should consider the ability to successfully operate a small business to be an important tentpole of individual liberty. But if you don’t subscribe to some of these more boutique elements of anti-bigness and are mostly concerned about market power, selective public ownership does everything that breaking up big companies does, except better and faster.

Matt Bruenig

Break Them Up!

For the past 50 years, the idea that market regulation would reduce freedom and human welfare dominated the field of economics. Enthusiasts for this neoliberal logic thought you could neatly separate questions of wages from questions of freedom.

As part of their project, the architects of the modern economy categorized antitrust as an exclusively economic tool (with no implications for democracy) and campaign finance as an exclusively electoral tool (with no implications for the economy). But Goliath corporations, predictably, used their incredible wealth to warp our democracy, using lobbying and “too big to fail” threats to shape policy and coerce workers. The economy became top-heavy, unstable, and vulnerable to shocks like Covid-19.

As we finally rethink neoliberal economics, there are progressive advocates who persist in re-creating its core error of separating questions of economic structure from questions of freedom. They argue that we should organize society around nationalized industries, in which shoes are manufactured by the government, carrots are grown by the government, and meat-packers, social media platforms, and office supply companies are run by the government.

Even putting aside the impact this might have on quality, supply, and innovation, universal nationalization is a terrible idea. I say this as someone who thinks we should expand the Department of Veterans Affairs’ model for healthcare, believes the Department of Defense should build more and contract less, and firmly supports public education over charters and private schools. While the government should run some sectors of the economy, it is critical that significant parts be left to the rest of us.

The goal of an economy is human flourishing, which requires the freedom to speak, to associate, to play, love, and worship. But real freedom also requires basic healthcare, livable wages, and the absence of domination. The wisdom of the anti-monopoly movement is that you can’t have the first two without the third.

An economy made for humans is one in which the people who build, work, sell, and negotiate do so from a position of meaningful dignity. Dignity requires the ability to say no, to turn away from a big corporation or a government employer. Freedom depends on decentralized power, on a web of industries that includes medium-size farms and producer-retailers, each making their own moral, aesthetic, and religious decisions.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The notion that freedom exists only on Election Day is nonsense. It’s like asking people to open their eyes once a year and expecting visual discernment. The exercise of freedom must be constant, and it must be socially embedded.

We see this problem when finance runs so much of the economy and when a handful of employers dominate regional employment. When Amazon sets the terms for delivery drivers within miles of its warehouse, it undermines the freedom of every worker in that area. But the same is true when the government dominates employment. The union rights of workers then exist only by the grace of a good government, and any system that requires grace—instead of embedding power—will not remain a wholly free one.

But each person will have a voice through elections; they will own sectors of the economy, you might say! Do you feel that way about the Department of Defense, arguably the most nationalized of our industries today? Or about Amtrak? I don’t think those should be privatized, any more than the incredibly important Tennessee Valley Authority should be privatized, but they should give you pause about a nationalized economy.

When people have been permitted to consolidate capital and leverage that power, we have seen how it leads to nursing-home deaths, poverty, and wage stagnation. The logic of investment overcomes community and seeks out ways to constrain the freedom of others. The government should not be so driven, the argument goes, and in many instances, the government can be more humane—but the logic of centralized power remains, and it too can overcome humanity.

For human flourishing, we need local power. For more than 140 years, the co-op model has been at the heart of the progressive vision for a just economy, and for good reason. But this is a vision of private industry, not of nationalization. We need an economy with worker-owned and producer-owned cooperatives. And we also need medium-size companies with unionized workforces competing for employees.

One of the grotesque errors of the 20th century was the belief that you could separate politics and economics, that power built in one arena would sit politely and not intrude into the other. The left must avoid this mistake and recognize that the anti-monopoly movement is a key part of human freedom.

Zephyr Teachout

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation