EDITOR’S NOTE: In the fall of 2021, a group of students at Wake Forest University took part in a class on data-driven advocacy. Their objective was to find a question that was broadly relevant to inequality, answer that question using basic tools of data science, and convincingly communicate that answer clearly to a broad audience in a partnership with the Puffin Nation Fund Writing Fellowships. This article is the fourth of the final products that came out of that course.

What is your life worth during a pandemic? During the two-and-half years of public health lockdowns and other limitations imposed to contain Covid, some have argued for minimal restrictions to preserve a strong economy even if it endangered the lives of the vulnerable.

Minorities endured a disproportionate share of the risk throughout the pandemic, composing much of the essential workforce without the luxury of being able to work from home. And the lockdowns had their own costs as well: Many mothers lost their careers and their independence as child care options vanished and numerous small businesses crumbled, leaving their owners economically vulnerable.

But perhaps the trade-off between economic well-being and public health was overstated. Because healthy people are the backbone of a productive economy, the best way to protect that economy may be to protect human lives. If this is true, as Juan Pablo Bohoslavsky argued, trying to put the economy first might paradoxically cause “the worst of both worlds: a fall in GDP and a rise in deaths.”

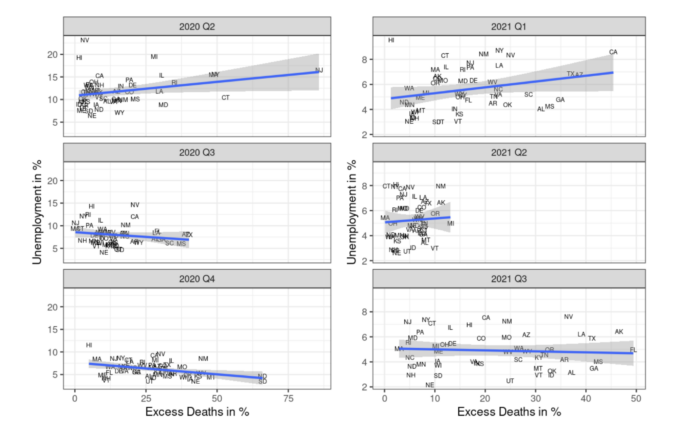

We found this argument compelling, so we set out to test the purported tradeoff between economic performance and Covid mortality using US data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Our data on excess mortality during the pandemic (i.e., the proportion of deaths during Covid above what would normally be expected) come from the National Center for Health Statistics. We also analyzed unemployment data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This data is organized by state and quarter; there is one observation for each American state starting in the second quarter of 2020 and ending in the third quarter of 2021. We then estimated a linear relationship between excess deaths in each state and the state’s unemployment rate separately for each time period.

Figure 1 below shows the relationship between excess deaths and unemployment in each of the six quarters from our data. There is substantial variation within the data across quarters: the explanatory power of excess deaths on unemployment is inconsistent throughout the entire pandemic. What this means is that there is likely no necessary impact on unemployment as death rates trend higher or lower, although in some quarters increased excess mortality may have pushed unemployment slightly higher. Ultimately, we found no meaningful relationship between excess mortality and the percent of the population that is unemployed.

Figure 1: Excess Deaths and Unemployment in the United States during the Pandemic, by Quarter

It is important that we emphasize that our finding no relationship between unemployment and excess mortality during the pandemic is itself a significant finding. The fact that unemployment is not being driven up or down as death rates change suggests that protecting public health will not undermine economic well-being if we can assume that unemployment percentages are an indicator of broad economic health across US states. If that is true, then we see in our data little indication of an economic disadvantage in prioritizing saving lives during Covid.

We speculate that keeping death rates down during the pandemic could return benefits to the economy in the long run. If people remain healthy, they will be more able (and more willing) to meaningfully participate in the US economy in the future as Covid becomes a less pressing threat. While there might not be any relationship at present between death rates and unemployment, there might be such a relationship in the future.