Ethisphere has a proprietary metric for assessing how morally correct companies are. This year, it gave an award to Israel’s largest weapons manufacturer.

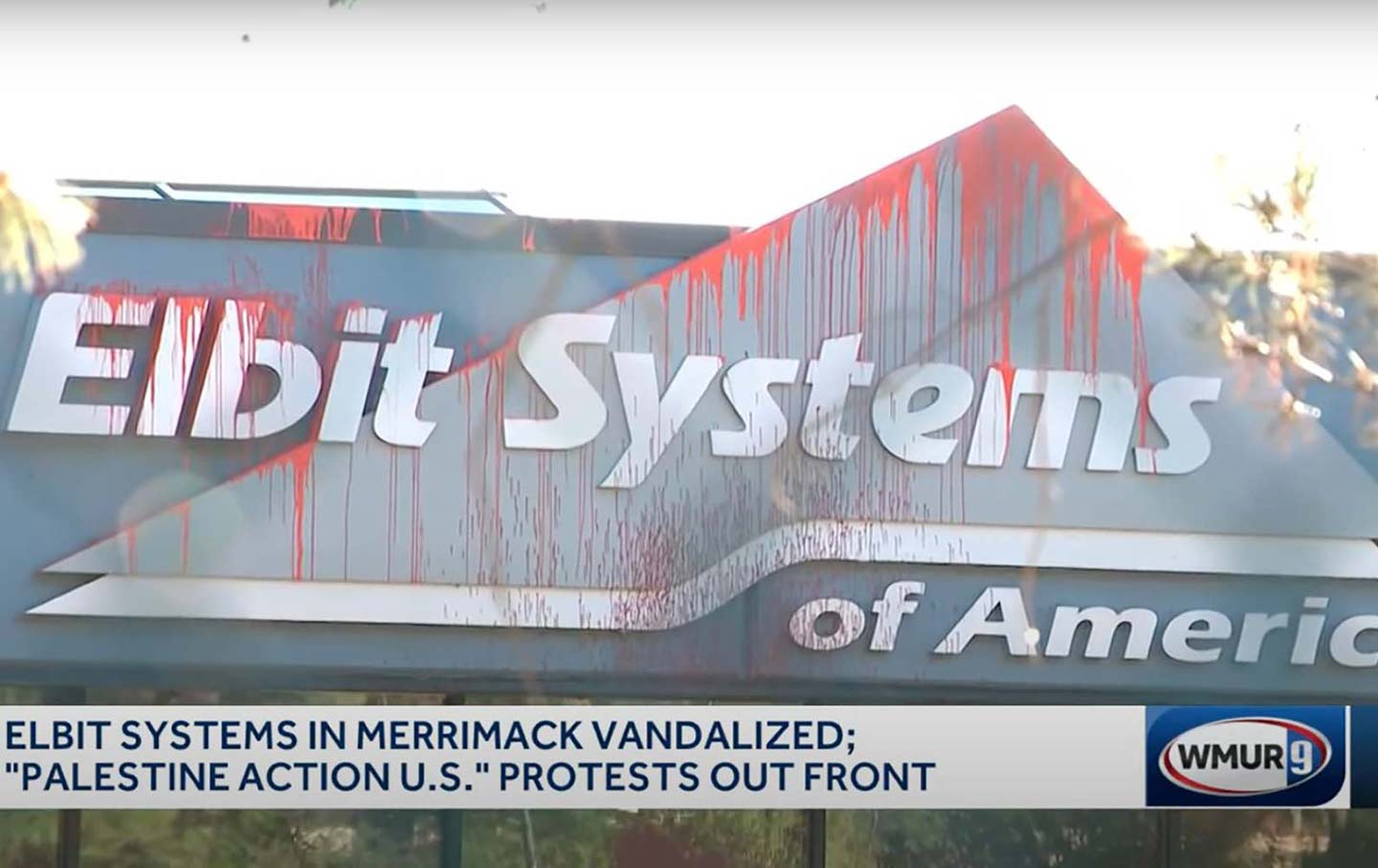

Elbit Systems of America facility in Merrimack, New Hampshire, after protesters showed up. (Screenshot from YouTube / WMUR-TV)

Eighteen years ago, in the wake of a series of fraudulent business scandals where major companies used accounting sleights of hand to cook their books, fool regulators, and gouge customers, people were fed up. So, the Ethisphere Institute and its World’s Most Ethical Companies list was born. “It occurred to the Ethisphere team,” Erica Salmon Byrne, Ethisphere’s chief strategy officer and executive chair, told me, “that there was nobody that was celebrating the companies that were doing things well.”

Ethisphere, a for-profit institution started in 2006, which describes itself as a tool to “accelerate ethical business,” has expanded significantly since its creation. In addition to producing its yearly list of the World’s Most Ethical Companies, Ethisphere hosts a podcast (Ethicast), a newsletter (“Ethisphere Insights”), and runs the Business Ethics Leadership Alliance, which allows members to access a “concierge” service where business executives can ponder ethical quandaries (“How do I measure and assess third-party risk?”) There is also a Global Ethics Summit, which occurs in tandem with the honoree gala. “It becomes evermore necessary to have a discussion about ethics,” the 2024 summit agenda reads, “and how we can maintain morality in our world.” Both nonprofits and for-profit companies can apply, with the exception of NGOs, government agencies, and nonprofit colleges and universities.

Last week, Ethisphere made its annual announcement of the 136 “most ethical companies” across the globe, prompting a wave of press releases, kudos from the financial world, and a video from one of this year’s winners, defense-contractor Booz Allen Hamilton. “Five time honoree” the celebration video says, a cartoon drone hovering beside it. Other awardees from this year include the pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly, the health insurance company Blue Shield of California, and the Fortune 500 toy manufacturer Hasbro.

It’s not a new thing, corporations using confusing acronyms and equations to congratulate themselves. There is CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) and ESG, a criteria for investments focused on Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance—or what conservatives call “woke capitalism.” But where Ethisphere differs is its focus on a quantifiable and astute-sounding measure, whose complexity seems to compel corporations into inherent trust. The press department at Ethisphere told me about its proprietary formula: the highly complex and trademarked, Ethics Quotient® methodology. Companies bestowed with the honor of scoring high enough can use the World’s Most Ethical Companies logo on their website and enjoy a glossy reputation-booster when seeking clients.

Some of this year’s honorees include seven-time winner Leidos, a weapons manufacturer that creates products for the US Army. Two years ago, the company was awarded the Pentagon’s “Project Mayhem” contract to develop an unmanned hypersonic aircraft. On its website it boasts “next-generation strike systems and technology for today’s warfighter.” Then there’s 10-time honoree—the US Bank—which the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau ordered to pay nearly $21 million last year after blocking out-of-work customers from receiving unemployment benefits at the height of the pandemic. “We work hard to ensure we do the right thing in everything we do,” noted a US Bank representative in its celebratory press release last week. This was the first year in several that the union-busting coffee chain Starbucks did not make the list.

The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) was awarded for the sixth time, despite being ordered to pay the federal government $8.5 million last year in a lawsuit over falsely billing federal programs, as well as jeopardizing patient health. In January of this year, a nurse filed a lawsuit against the hospital for the UPMC’s unfair business practices.

But the company that really takes the cake is six-time honoree Elbit Systems of America, a subsidiary of Israel’s major weapons firm Elbit Systems. The company’s Israeli counterpart reportedly supplies around 85 percent of the IDF’s drones and land-based equipment, which as of late have been used to kill residents of Gaza. Elbit doesn’t shy away from its involvement in Palestine: The company’s website advertises its “Iron Sting” weapon, which features “neutralization of targets” within six and a half miles as the answer to the “complex reality” following October 7. It has also been involved in the militarization of the US-Mexico border, and last year were awarded a contract to provide surveillance towers along the northern and southern borders of the US.

On its website, Elbit advertises its 2023 “Ethisphere ethics inside certification” alongside values like “BE BOLD,” “BE OPEN,” and “DO THE RIGHT THING.” Over the past five months, protesters have targeted Elbit Systems and its various overseas offshoots for its role in the attacks on Gaza. Last month, a major Japanese corporation cut ties with the firm for similar reasons, and in late February, three activists were indicted for pouring red paint all over the company’s New Hampshire office and climbing on its roof. Elbit, obviously, is hardly the highly principled crusading business that the awards system claims to highlight.

When asked how these practices, particularly the creation of weapons that kill thousands of people each month square with an ethical world, Salmon Byrne told me there have been multiple internal discussions about the contradiction. “You use the word ‘ethics,’ and it has such an emotional resonance for so many people, and everybody has a slightly different definition of what ethics is to them, personally,” she said over a Zoom call. “What we’ve really tried to do over the years is think about the role that a company plays in the broader world and ask ourselves, ‘What are the things that would tell us that the company is doing to try to commit to a certain kind of corporate behavior?” (I paused at “corporate behavior.” What is good corporate behavior?)

The mathematical methodology used for assessing good ethics has skewed toward internal company ethics, Salmon Byrne said, “as opposed to ‘Is the product that they put out ultimately something that everybody would personally agree with from their own sense of individual ethics?’” I wondered what Salmon Byrne’s moral compass was telling her. When I had started listing the weapons companies that featured prominently on Ethisphere’s list, I forgot the name of one and stammered. “I’m forgetting the other one,” I said, “I think it starts with L.” Salmon Byrne interjected: “Leidos.” This caught me by surprise, as I’d naïvely assumed that the leaders at Ethisphere might be afraid of admitting that they’d put this kind of company on their list. After all, while Salmon Byrne was happy to be interviewed, journalists are not allowed to attend the celebratory gala in April, held at a hotel in Atlanta, Ga. (Seats range from $850 for an individual ticket to $10,500 for a table of 10.)

Salmon Byrne, however, was more than happy to share the secrets behind the Ethics Quotient®. The methodology consists of a survey where applicants respond to some 240 questions in five different sections. The 2024 questionnaire asks, among other things, what percentage of board directors “self-identify as female or non-binary,” how a company’s board oversees its “talent/ human capital strategy,” and “does your organization have a policy on policies?” The survey also covers mental health care for staff, and the number of public company boards that directors sit on. A “methodology committee” then analyzes the survey answers, resulting in what Salmon Byrne calls, impenetrably, an “unverified ethics quotient.” Then, an Ethisphere review team compares documentation to survey answers and produces the “verified ethics quotient,” the ranking number used to decide who makes the list each year. As for how many applicants there are, that is a tightly held secret.

“We are so paranoid about anybody ever knowing who has raised their hand for consideration,” Salmon Byrne said. “Because, as you can imagine, if you raise your hand and don’t make it, it’s really sensitive. So, we don’t actually ever disclose the number of applicants we get, because we don’t want anybody to try and reverse engineer and figure out who they can embarrass.” Like everything else that shapes Ethisphere, appearances are everything.

Entering the running for the World’s Most Ethical Companies list is not free. Ethisphere charges $3,500 to enter if you are a company that operates in 24 or fewer countries, and $4,500 if you operate in 25 or more countries. Because the company won’t say how many companies enter each year, it’s impossible to know how much it profits from entries alone. But we can safely say it’s at least half a million dollars.

Last November, a group of philosophers signed an open letter, titled “Philosophers for Palestine,” urging the boycotting of academic and cultural Israeli institutions via PACBI and a general direction to speak out and advance the cause of Palestinian liberation. “We do not claim any unique authority—moral, intellectual, or otherwise—on the basis of our being philosophers,” the letter read. “However, our discipline has made admirable strides recently in confronting philosophy’s historically exclusionary practices.” Among the signatories was Mark Lance, a professor of philosophy at Georgetown University who cofounded the school’s Justice and Peace Program. Lance told me focusing on the role corporations play in criminal oppression by governments is a cornerstone of international solidarity work. “To award a company as ‘moral’ when it is directly violating the boycott call of the Palestinian people in the most direct way possible [and] by supplying military hardware to the IDF is to make a mockery of the very notion of morality or ethics,” Lance said when we discussed Elbit’s place on Ethisphere’s list.

It’s an example of “bourgeois morality” that looks at how polite someone is locally, rather than the effects of their actions, Lance said. “That attends to the feelings of valuable white people, and looks the other way when brown bodies are burned alive by white phosphorus.… It matters not one jot how vigorous a DEI [diversity, equity, and inclusion] program Elbit employees enjoy, so long as their work is contributing to the murder of 12,000-plus children.”

Going back to the Ethics Quotient®, Salmon Byrne said that the weighted scoring system dedicates 20 percent of its scoring to “impacts.” “What we mean is the way in which you as an organization are impacting the communities and the world around you,” she said. This is where the experts measure not how many National Labor Relations Act violations a company has racked up but rather the company-reported mental health of employees at work and its measures of DEI and corporate philanthropy. “All those different ways you as an organization, as a company, rather, can influence the communities in which you operate.”

What “the experts” are really measuring is not how a company’s products are used in the real world but rather how its internal structure plays out in the office. While it’s nice to know that an organization has a “good work culture,” you would think that a company with a tagline like “most ethical” would be a more upstanding, righteous kind of operation than one that engages in dodgy billing to maximize profit, freezes unemployment benefit payments, or produces killer weapons. Just as greenwashing makes dirty companies look slightly better by instituting bare-minimum environmental protection policies, and pinkwashing distracts from human-rights violations by pointing to alleged LGBTQI+ friendly actions, what we have here is ethics-washing: You can cause harm, as long as there are ethical methodologies—preferably trademarked ones—to back it up.

Jess McAllenJess McAllen is a journalist from New Zealand and currently a staff writer at The Baffler.