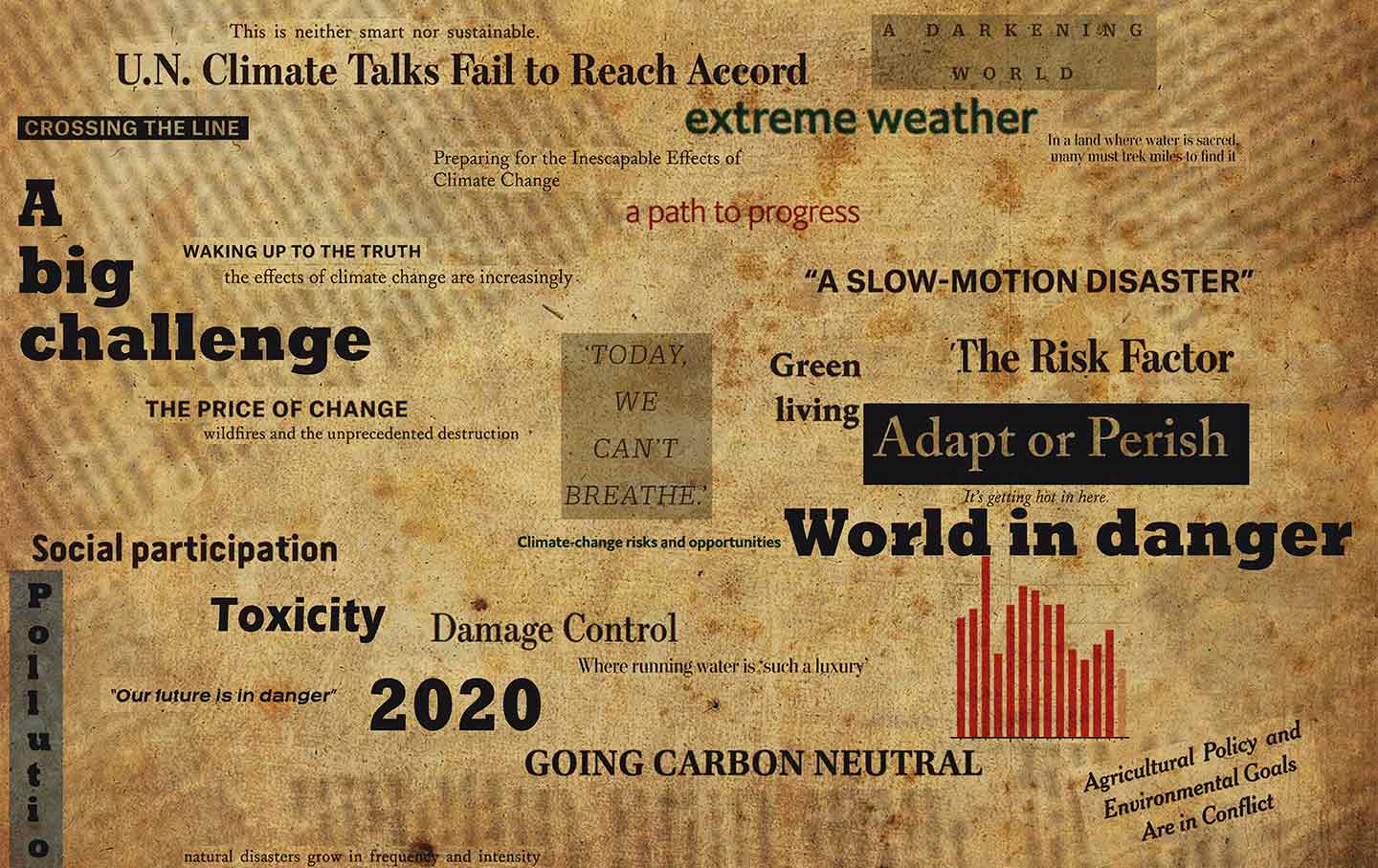

Newspaper headlines.(Creative Lab / Shutterstock)

This article is adapted from “The Climate Beat,” the weekly newsletter of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism initiative committed to more and better climate coverage.

The coronavirus is a fierce reminder of just how much we need credible journalism, especially in times of crisis. And there’s been much to admire in the media’s coverage of the coronavirus crisis. Timely, accurate, high-profile reporting has helped Americans understand the danger of the virus and how to contain its spread through measures such as social distancing.

To varying degrees, the coverage has also held authorities to account for their handling of the crisis, with President Trump under particular scrutiny after spending weeks dismissing the pandemic as “no big deal” and even a “hoax” before pivoting to claim that he knew it was a pandemic all along.

But the media’s snapping to attention on coronavirus throws its coverage of the climate crisis into sharp relief. The press has never treated the climate story with anywhere near this level of attention or urgency. To be sure, climate coverage has improved in recent years. Flagship outlets including The Washington Post and The New York Times have significantly upped their game. And there was an unmistakable surge of climate coverage last September, amid global youth climate protests, the United Nations Climate Action Summit, and the increased ambitions of news outlets affiliated with the Covering Climate Now initiative. At the time, it looked like coverage of the climate story had at last turned a corner. But coverage by most outlets, at least in the United States, subsequently waned.

The contrast between the media’s coverage of the coronavirus and the climate crisis illuminates another core truth about the media. Collectively, the media exercises perhaps the greatest power there is in politics: the power to define reality, to say what is—and what is not—important at any given time. The coronavirus has correctly been treated as supremely important, dominating virtually every home page and broadcast. Stories on other subjects have all but disappeared, and some newsrooms have halted production on non-coronavirus stories altogether. While this is understandable given the scope of the Covid-19 threat, it is bizarre that the climate crisis has never been accorded comparable importance, even though it too stands to upend, impoverish, and even end the lives of countless people the world over.

This is partly a matter of perception: The coronavirus is an immediate and concrete threat—it might sicken any of us today—whereas climate change is often framed as an ever-looming threat that imperils other people, somewhere else. But that perception is faulty: Just ask the millions of people who have already lost homes, livelihoods, or loved ones to the bushfires in Australia, the hurricanes that have pounded the Caribbean, or the droughts, floods, and other climate-related disasters that have punished communities from Missouri to Myanmar. Sooner than later, climate change will become less abstract for us all.

But why must newsrooms—especially the lucky few that have sufficient resources—choose between the coronavirus and climate stories? Both the Covid-19 pandemic and the climate crisis carry enormous stakes, and neither puts the other on pause. With its threats to individuals’ health, national economies, and social life, the coronavirus is “climate change at warp speed,” Gernot Wagner, a climate economist at New York University, put it. A Guardian article explained that “Delay is deadly,” adding that, globally, “right-wing governments have denied the problem and been slow to act. With coronavirus and climate change, this costs lives.”

Both scientific reality and journalistic responsibility call upon newsrooms to treat the climate crisis as an emergency no less pressing than the coronavirus. As with the virus, they can start with the necessity of “flattening the curve”—which, thanks to all the media coverage, has become a household phrase. There is now widespread understanding that early and wide-ranging intervention is crucial to limiting the virus’s spread. Now, journalists must help their audiences understand that flattening the curve of greenhouse gas emissions is just as imperative, and the longer we wait to reduce those emissions, the greater the eventual damages will be.

There are dozens of ways to tell that story, which at heart is a story about solutions: Which nations or companies or individuals have been most successful at flattening the curves? What are their secrets? What can the rest of us do to help?

The federal government’s abrupt willingness to spend trillions of dollars to keep the US economy aloft demonstrates that a lack of money has never been the main reason for rejecting climate solutions such as a Green New Deal. So the media’s all-hands-on-deck approach to the coronavirus suggests that lack of journalistic resources was not what kept news outlets from prioritizing the climate story. Newsrooms have the skills, smarts, and grit required to rise to both challenges; the question is one of will, more than capacity. No matter how well we cover one of these crises, it won’t matter much if we fumble the other.

Mark HertsgaardTwitterMark Hertsgaard is the environment correspondent of The Nation and the executive director of the global media collaboration Covering Climate Now. His new book is Big Red’s Mercy: The Shooting of Deborah Cotton and A Story of Race in America.