The View From Whole Foods

The transformation of Gowanus

The Transformation of Gowanus

Can a Superfund site be remade into an experiment for equitable housing and eco-friendly development?

One of the bridges over the Gowanus Canal.

(Spencer Platt / Getty )

Roughly 15 years ago, I stood on the banks of Business Bay, a man-made extension of the natural waterway where the city of Dubai was founded, gazing across the water at the 163-story Burj Khalifa, then under construction, and an entire skyline’s worth of lesser towers—all being erected at once. The Emirati developer who had taken me to this viewing spot explained, “We are trying to build in 10 years what other people take 100 years to build.”

I recalled this scene recently while standing on the roof deck of the Whole Foods in Brooklyn’s Gowanus neighborhood, a once-obscure section of the borough named after its profoundly polluted canal. I gazed past the store’s parking lot with its eco-friendly gestures—photovoltaic panels atop uptilted parking canopies and tiny egg-beater-style windmills mounted on poles—and took in a small city’s worth of buildings, maybe even 100 years’ worth, that hadn’t existed the last time I checked.

The view from Whole Foods was the product of a rezoning effort that began in 2016 and was finalized in 2021, with the goal of transforming a neighborhood once dominated by industry and its toxic by-products into a high-density residential area. The aim was to build around 8,500 new apartments over the course of 15 years, including roughly 3,000 affordable units, in an area best known for being a Superfund site.

However, it looks and feels as if every single one of those apartments is being constructed at once. (According to the Department of City Planning, permits were issued for 52 buildings containing 7,450 apartments between the adoption of the new zoning in late 2021 and the end of 2023.) From atop Whole Foods, I could see several completed blocks of mid-rise buildings lining the banks of the canal, and more under construction. Then, farther north, stands a cluster of glassy high-rises nearing completion. Nearby, almost next-door, is a rust-colored building that, more than a century ago, was built as the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Power Station to provide electricity to the borough’s streetcar system. Now, after years of abandonment—in the early 2000s, it was known to squatters and graffiti artists as the Batcave—it has been stunningly rehabilitated into an arts hub by the renowned Swiss architecture firm Herzog & de Meuron, working with a local company, PBDW Architects.

Powerhouse Arts, as the facility is now known, is a nonprofit organization that provides space to local artists, craftspeople, and fabricators. The building’s great hall, with its brick walls covered in Batcave-era graffiti, is Brooklyn’s version of that cave in Lascaux. From its windows, one gets another set of views of a changing neighborhood. The Powerhouse, with its artistic leanings, feels like a rebuke to the development happening all around it, and yet it may be the ultimate symbol of that transformation.

Gowanus, the neighborhood, is a low-lying piece of ground between the more desirable Carroll Gardens and Park Slope. Its canal is the product of the mid-19th-century penchant for transforming natural waterfronts into industrial zones. Once a creek that meandered through a bucolic salt marsh, it soon became one of the nation’s most heavily used shipping channels, lined with gas plants, foundries, and coal yards. Serving as a terminus for goods and natural resources, the canal also became filled with toxic by-products. In 2010, it was declared a Superfund site, and contractors hired by the original polluters’ corporate descendants (most notably National Grid), under the supervision of the Environmental Protection Agency, began to dredge some 10 feet of sediment from the canal’s bottom to remove coal tar and other deadly contaminants.

Gowanus has long been, both literally and figuratively, a backwater. It is home to two massive public housing projects, the Gowanus Houses and Wyckoff Gardens, with a total of 1,662 apartments, though until recently, much of the neighborhood’s housing has been small two- and three-story row houses. In addition, there are endless blocks of low-rise brick industrial buildings, a few of which are still used for manufacturing. One open doorway on Nevins Street reveals a factory making Santeria candles.

Like all undervalued and overlooked areas, Gowanus also has its fair share of artists, who have used the old warehouses and low-density manufacturing sites as residences and studios. But Gowanus took longer to gentrify than the other New York City industrial zones colonized by artists. Perhaps because it is a bit out of the way, primarily served by the painfully local R train, it was slow to change: The remaining old-timers still spend their summer evenings sitting in beach chairs on the sidewalks.

Gowanus was also my first home in New York City. In 1984, I rented a $525-a-month floor-through with a shower in the hall, in a building on Union Street, half a block from the canal. From my apartment’s windows, I could monitor the comings and goings of an older New York, watching the workers from a local casket manufacturer wheel the finished coffins—some decorated with bas-reliefs of The Last Supper—across the street to a warehouse and shipping facility on the other side of Union. Back then, the only person talking about neighborhood transformation was Salvatore “Buddy” Scotto, whose family owned a liquor store and a funeral home in Carroll Gardens. He’d tell anyone who would listen that the canal should be an attraction like the San Antonio River Walk.

For many years—decades, really—the idea of a different Gowanus wasn’t anyone’s top priority. The old Gowanus remained mostly intact, even as the surrounding Brooklyn neighborhoods were gentrified. Now, though my former building and its immediate neighbors still stand, the old neighborhood is rapidly being replaced. The casket company is gone; it sold its properties to developers in 2019. The warehouse is being supplanted by 585 Union Street, a massive nine-story mixed-use building with an undulating façade designed by the architecture firm Fogarty Finger; it will have 224 apartments, 25 percent of which have been designated as affordable.

Across the street, another astonishingly huge complex is under construction that will occupy much of the block between Union and President streets—including the site of the casket factory. Cantilevered menacingly over the flagship of the now-defunct Ample Hills ice cream empire, it also wraps around the Royal Palms shuffleboard bar; both businesses were harbingers of change, along with an influx of artisanal eateries, stylish barbecue joints, and the inevitable microbreweries.

Stubborn bits of the old Gowanus do remain. The two public housing complexes aren’t going anywhere. Nor are many of the artists: At the northwest corner of Union and Nevins, a little pottery shop sells wheel-thrown porcelain by the potter Claire Weissberg. Her building has housed artists since the 1970s and has been owned collectively by them since 2005. The Gowanus Dredger Canoe Club, an intrepid group of urban naturalists that has been offering canoe rides on the canal since 1999, occupies a plum storefront in one of the new mid-rise buildings on the canal.

The presence of the holdouts, however, only underscores the vastness of the reinvention all around them. Walking around Gowanus, it’s easy to recoil in horror at the scale of the undertaking. It’s reminiscent of what happened along the Williamsburg-Greenpoint waterfront after those neighborhoods were rezoned in 2005 and the crumbling industrial buildings that had been reclaimed by artists and assorted counterculture types were replaced wholesale by swank apartments. “Certainly, the construction is all happening at once,” acknowledges Andrea Parker, the executive director of Gowanus Canal Conservancy (GCC), an organization founded in 2006. “The reason that’s happening is that the planning process leading up to the Gowanus rezoning lasted, I think, far longer than anyone expected.”

Of course, it is not just the length of the planning process that has driven the current frenzy. It is also the fact that developers had to get their buildings started to take advantage of a tax break known as 421a, which was about to be abolished by the New York State Legislature. Originally, for new buildings to qualify, they had to be completed by 2026, but in late April the deadline was extended to 2031. (Governor Kathy Hochul’s 2025 budget also replaces the old tax break with a new one, 485x, with a revamped set of affordability rules for participating developers.)

Parker, who was trained as a landscape architect, is deeply concerned about the environmental management of the canal and its growing number of green spaces, including green roofs and rain gardens. But that doesn’t make her an opponent of the development. And that’s the unusual part of this story.

Along with 30 community members, including residents of the public housing complexes (which are run by the New York City Housing Authority) and leaders of a variety of long-standing neighborhood groups, Parker is part of something called the Gowanus Oversight Task Force, a volunteer organization formed specifically to oversee the deal that the community made with the city. The quid pro quo gave the city its rezoning in exchange for a broad range of public benefits, including a waterfront park, a new school, a rehabbed library, affordable housing, flood control, and the continued existence of an area zoned for industrial use.

Traditionally, development battles in New York City pit real estate interests with a plan against local residents who oppose it. But what is happening in Gowanus, once you get past the frenetic construction, is something more interesting: A coalition of neighborhood organizations went into the process knowing what it wanted and came out with tangible gains.

In the early stages, an organization called the Gowanus Neighborhood Coalition convened residents of the Gowanus Houses and Wyckoff Gardens, the leaders of a nonprofit developer of affordable housing called the Fifth Avenue Committee, a number of local arts organizations, and environmental groups including the GCC. This coalition came up with over 50 “points of agreement,” including comprehensive in-unit renovations for all of the apartments at Gowanus Houses and Wyckoff Gardens and the “full remediation” of a former gasworks that will become Gowanus Green, a neighborhood-scaled affordable housing development. Master-planned by the architecture firm Marvel, it will have approximately 950 units, a public school, and a waterfront park.

One of the most significant benefits that the neighborhood extracted from the rezoning process is a commitment to the Gowanus Lowlands Master Plan, drafted by the GCC and the landscape architecture firm SCAPE in 2019. The plan offers a sophisticated template in which the cleaned-up canal becomes the spine linking a series of public spaces, including waterfront parks, esplanade gardens, and maybe even a couple of public restrooms. “By 2031 or ‘32, we’ll have, overall, a 20-acre network of parks,” Parker notes. And unlike the discrete parks built by developers along the East River waterfront under the 2005 rezoning of Williamsburg and Greenpoint, “it will all connect.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In addition, rain gardens and green roofs will play an important part in mitigating the flooding caused by heavy rains, and the new buildings are required to store their wastewater on-site during storms. Two massive tanks designed to contain what’s known as “combined sewer overflow” (or CSO) are being built at opposite ends of the canal. One of the CSO facilities, at the corner of Douglass and Nevins streets, will hold 8 million gallons in a set of underground tanks housed in a building designed by Selldorf Architects (the firm responsible for the visitor-friendly waterfront industrial recycling facility in Brooklyn’s Sunset Park).

The tanks will be hidden behind walls made of terra-cotta louvers that will “unveil in certain areas the internal process to the public,” according to the architect’s website. The facility will also be surrounded by a 1.6-acre public space and educational displays about the history of the neighborhood and the nature of the technology within. It’s a bold switcheroo in which the neighborhood’s long-standing sewage problem morphs into an amenity or maybe even an attraction. In a way, it’s emblematic of the whole lemons-to-lemonade approach to the neighborhood’s transformation.

What appears at first glance as a cataclysm is, on closer inspection, a possible model for how New York City neighborhoods should manage the business of growth and the addition of much-needed housing.

Parker says the neighborhood coalition won “an unprecedented quantity and scope of commitments to neighborhood benefits” from the city as part of negotiations during the upzoning. “But so often in New York, the City makes commitments and does not follow through.” One of the “deal-breaker” demands of the Gowanus Neighborhood Coalition for Justice was accountability, and a task force was formed to monitor the city’s adherence to the agreement. “The city has to report progress on the commitments to the Gowanus Oversight Task Force on a quarterly basis,” Parker adds.

In 2019, when the Gowanus rezoning was still a work in progress, I spoke with Brad Lander, then the city councilmember whose district covered much of the neighborhood. The conversation was mostly about how narrow and reductive public participation in planning generally is, the YIMBY-versus-NIMBY dynamic. Lander pointed to the Gowanus plan and explained, “We decided to work together and build something more like political power, to go to City Hall and say, ‘Here are the principles we support. If you are willing to live up to those principles, then we could support a rezoning.’”

Recently, I asked Lander, now New York City’s comptroller, whether that strategy of amassing political power could be a model for how a city that desperately needs more housing—and especially more affordable housing—might make plans that benefit everyone. “I think we did a good job in the planning process, but really what I think mattered is that people had built institutions over the years which built civic power for their values,” Lander replied. “That civic power was able to show up through a planning process. And that’s not easy to replicate.” But, he added, it is not impossible. In “a certain way, this is just democracy, with grassroots organizing elaborated in land use.”

So the next time you find yourself on some Whole Foods roof deck staring in disbelief at a neighborhood being consumed by construction, how you interpret what you see might depend on your faith in civic power. Because the quality that Lander cited—“just democracy”—is the very thing that’s being tested everywhere, no matter which way you look.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Fight for the Last Wild Salmon The Fight for the Last Wild Salmon

In Alaska, the last stronghold for wild salmon, Native tribes and conservationists are working to save the fish from both climate change and decades of corporate greed.

What Your Cheap Clothes Cost the Planet What Your Cheap Clothes Cost the Planet

A global supply chain built for speed is leaving behind waste, toxins, and a trail of environmental wreckage.

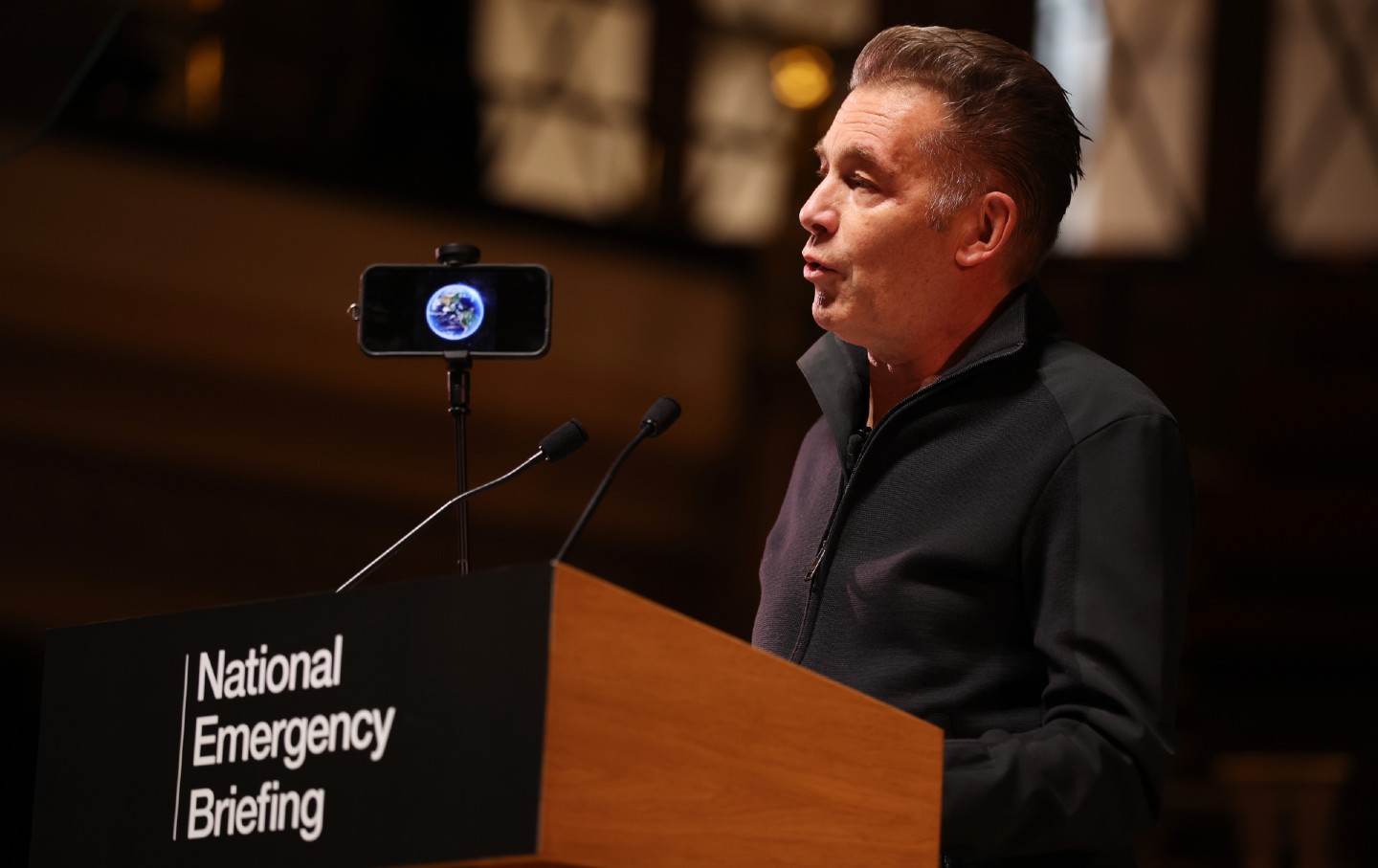

The UK’s Climate National Emergency Briefing Should Be a Wake-Up Call to Everyone The UK’s Climate National Emergency Briefing Should Be a Wake-Up Call to Everyone

The briefing was a rare coordinated effort to make sure the media reflects the science: Humanity’s planetary house is on fire, but we have the tools to put that fire out.

AI Will Only Intensify Climate Change. The Tech Moguls Don’t Care. AI Will Only Intensify Climate Change. The Tech Moguls Don’t Care.

The AI phenomenon may functionally print money for tech billionaires, at least for the time being, but it comes with a gargantuan environmental cost.

Backsliding in Belém Backsliding in Belém

Petrostates at COP30 quash fossil fuel and deforestation phaseouts.

Wake Up and Smell the Oil. Your Nation’s Military Is Hiding Its Pollution From You. Wake Up and Smell the Oil. Your Nation’s Military Is Hiding Its Pollution From You.

A fact all but ignored at COP30.