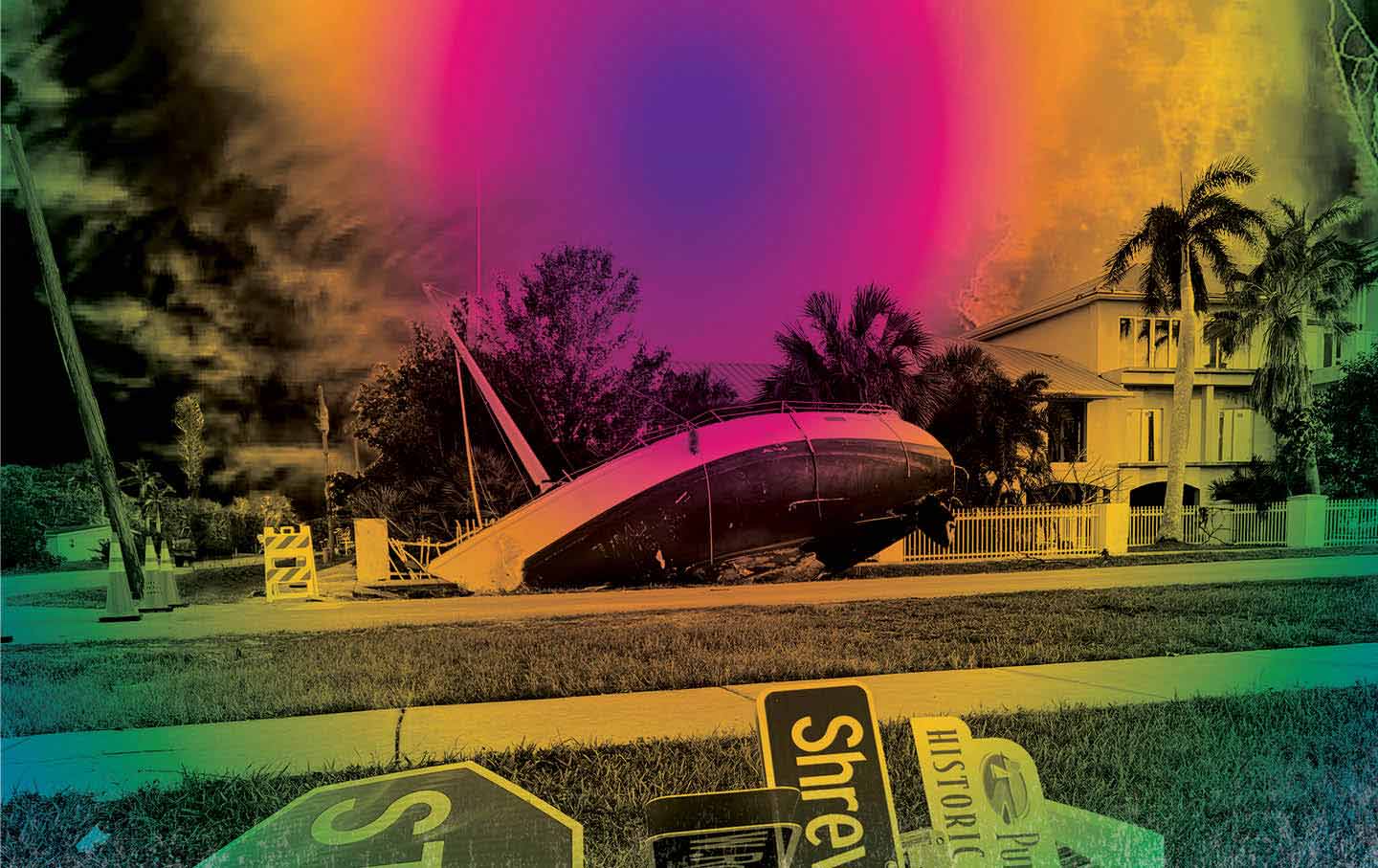

In the wake of Hurricanes Helene and Milton, it’s clear we’re defending against the wrong perils.

At the beginning of each year, the director of National Intelligence provides Congress with a report on “worldwide threats to the national security of the United States.” And over a dozen years or so, the DNI’s report has consistently identified the same four nations as constituting the “most direct, serious threats” to US security: China, Russia, North Korea, and Iran. The ranking of these antagonists has varied over time, with China receiving top billing in the 2024 edition, but all four are routinely singled out for extensive discussion in the DNI’s annual report. Only after many pages of such analysis, in a section on “transnational issues,” are we told that climate change also poses a risk to US security, by triggering mass migrations and unrest overseas. Missing from the DNI’s warning, however, is the threat that climate change poses to our country—to our lives, communities, and vital infrastructure. Now, in the wake of Hurricanes Helene and Milton, this oversight should be recognized as one of the nation’s greatest intelligence failures ever.

Climate change is not, of course, a nation-state with a powerful military and weapons stockpiles. Yet it constitutes an aggressive force no less powerful than China and the other potential adversaries mentioned in the DNI assessment—one that has shown itself capable of flooding our cities, inundating our coastlines, burning our forests, and decimating our farmlands. And while we’ve spent trillions of dollars on the ostensible effort to defend our country and our allies from hostile nations, we’ve done pitifully little to protect ourselves or others from the destructive forces of climate change.

Hurricanes Helene and Milton will long be remembered for the human misery they inflicted on the residents of Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and the Carolinas. At least 234 people died from the effects of Helene, another two dozen from Milton, and as of October 15, 100 people were still missing. Many thousands more lost their homes or livelihoods—or both. While it is still too early to calculate the monetary value of property and infrastructure losses from the two megastorms, estimates of $200 billion or more do not appear to be exaggerated. It will be a long time before some affected areas fully recover, if ever.

The destructive powers of Helene and Milton were vastly amplified by the effects of climate change. As we dump our carbon and methane waste into the atmosphere, feeding the greenhouse effect that is responsible for rising global temperatures, an estimated 90 percent of the excess heat produced in this manner has been absorbed by the world’s oceans—raising water temperatures and thereby generating the energy that transforms ordinary hurricanes into superstorms like Helene and Milton. Waters in the mid-Atlantic and the Caribbean—the birthplace of most hurricanes that make landfall in the US—were hotter this spring than in any previous spring on record, “with over 90% of the area’s sea surface engulfed in record or near-record warmth,” Yale Climate Connections reported in May. The fact that the two massive storms occurred within two weeks of each other, multiplying the damage in some coastal areas of Florida that were exposed to both, is another consequence of a warming and increasingly chaotic climate system.

The harsh impacts of Helene and Milton have been well covered by the media and so are familiar to most Americans. But the national security implications of the two storms have received far less attention, even though the long-term consequences for our national security are no less severe. These include:

Mobilization of military support.

As storms become more severe on a warming planet, local authorities (including police, medical facilities, and emergency services) will become increasingly overburdened and in some cases overwhelmed and unable to perform their essential functions. This, in turn, will require the mobilization of the National Guard and active-duty military forces to assist with search and rescue (SAR), food and water distribution, recovery operations, and the basic tasks of government. The Pentagon calls operations that involve active-duty troops “defense support of civilian authorities” (DSCA, pronounced “disca”).

As of October 13, more than 11,000 National Guard soldiers and airmen from some 19 states were deployed in relief missions in the southeastern US in the wake of Helene and Milton. “Using helicopters, boats and high-water vehicles, they rescued people stranded by flooding and high and swift water,” the Army reported. But even this vast mobilization of Guard forces was not deemed sufficient to address the hurricanes’ impacts. On October 2, President Joe Biden ordered the immediate deployment of 1,000 active-duty troops to hard-hit areas of Tennessee and North Carolina to assist in SAR, food delivery, and road clearance. Four days later, after touring areas affected by Helene, Biden ordered another 500 troops to assist in the efforts.

“These active-duty troops,” the White House said in an official statement, “are focusing their efforts on moving valuable commodities—like food and water—to distribution sites, getting those commodities to survivors in areas that are hard to reach.”

The Army and Navy personnel that were mobilized for this purpose represented only a small fraction of the nation’s active-duty force, so other troops were available to address any conventional threats that might arise, such as a war in the Middle East or a conflict with China over Taiwan. But as climate-change-fueled superstorms become more frequent and damaging, the Defense Department will be forced to provide an ever-increasing number of troops, ships, planes, and helicopters for DSCA operations. At some point, top officials fear, these missions could overtake conventional combat preparedness as the Pentagon’s top operational obligation.

The immobilization of military forces and assets.

Hurricanes Helene and Milton forced the evacuation not only of civilians from their communities but also of military personnel and equipment from key bases in the Southeast, further diminishing US military preparedness.

On September 26, as Helene bore down on the Florida Panhandle, the Air Force issued evacuation orders to nonessential personnel at the MacDill and Tyndall Air Force bases in the state and at Moody AFB in Georgia and redeployed aircraft from other facilities further inland. Tyndall, which had suffered catastrophic destruction from Hurricane Michael in 2018, largely escaped serious damage this time around, but MacDill and Moody were flooded and lost electrical power. Fort Eisenhower, a major Army installation near Augusta, Georgia, was also placed under evacuation orders as floodwaters surged onto the base, knocking out power. Some buildings at all three installations were destroyed or damaged, including housing for military personnel and their families.

The approach of Hurricane Milton just over a week later prompted similar evacuations in the Southeast. MacDill, which sits just above sea level on a peninsula in Tampa Bay, ordered nonessential personnel to evacuate once again. Essential personnel at the headquarters of the US Central Command and the US Special Forces Command—both located at MacDill—remained on duty, but some facilities were damaged by the storm.

Other bases in the Southeast also were evacuated, including Homestead Air Reserve Base near Miami and Naval Station Mayport in Jacksonville. In anticipation of the storm, the 482nd Fighter Wing at Homestead redeployed some of its F-16s to a base near San Antonio, Texas, and officials at Mayport sent three of the destroyers stationed there out to sea to escape damage in port.

These evacuations and dispersals of equipment caused only a minimal reduction in overall US military preparedness, as was true of the DSCA operations in North Carolina. But taken together, the two undertakings represent a significant disruption to US military capabilities in the nation’s Southeast, the home to a vast network of bases and facilities. If the United States were at war, this would be considered a major strategic setback. Disruptions like these, moreover, are sure to become more frequent and severe as global temperatures rise, a prospect that is forcing the Pentagon to rethink its plans for future troop deployments—including by retaining more forces at home to cope with domestic climate disasters.

Leadership distraction.

On October 8, with Hurricane Milton about to make landfall on Florida’s Gulf Coast, Biden postponed critical trips to Germany and Angola so that he could oversee the federal response to the storm damage. “I just don’t think I can be out of the country at this time,” he declared. But while the White House considered it politically necessary to demonstrate concern for US citizens during the run-up to a presidential election, the cancellations represented a major geopolitical setback.

In Germany, Biden was scheduled to meet with President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine and representatives of 50 other nations to expedite the delivery of arms and other vital equipment to Ukrainian forces. The New York Times described the cancellation as a “blow” to Zelensky, who was trying to rally Western leaders to support his nation’s overstretched forces before the US election, which many European officials feared would result in the return of Donald Trump to the White House and a cutoff of US aid to Ukraine. In the meantime, Biden’s ability to rally international support for Ukraine is evaporating.

Similarly, Biden’s visit to Angola, which would have been his first to any African nation as president, was intended to energize US efforts to compete with China and Russia in the pursuit of Africa-wide geopolitical advantage. Again, the administration says Biden will reschedule the meeting, but doubts have arisen over the feasibility of the trip in the few months remaining of his tenure.

As climate change accelerates, major strategic quandaries like these will occur ever more frequently, as leaders are forced to concentrate on recovery efforts at home. This means that future presidents will have to be far less ambitious in the sphere of geopolitical competition, including the pursuit of foreign alliances. Such a retreat from international ambitions will, of course, be welcomed by many in the United States—but it will also constitute a major shift in the country’s approach to national and international security, and must be viewed as such.

Infrastructure damage and overstretched resources.

Finally, it is essential to consider the effects of climate change on the nation’s water, power, and transportation infrastructure, and our capacity to overcome the consequent damage and disruptions.

Hurricanes Helene and Milton did not inflict as much damage to critical infrastructure as did Katrina in 2005 and Sandy in 2012, but they did exhibit, once again, the capacity of severe storms to disrupt vital systems. Helene is reported to have knocked out power for 5.5 million customers in Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas, Tennessee, and Virginia, and Milton disrupted service for at least 3 million customers in Florida (of which some 450,000 still lacked power as late as October 14).

Water facilities were also affected by the monster storms. In Asheville, North Carolina, a thriving municipality of 94,000 people, the flooding caused by Helene destroyed much of the city’s water supply system. “The system was catastrophically damaged, and we do have a long road ahead,” said Ben Woody, Asheville’s assistant city manager. Damage to transportation infrastructure in the area was also severe: Parts of two major highways, Interstates 26 and 40, were washed away by the floods, and repairs are expected to take many months and cost in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

The Biden administration has promised vast dispersals of federal aid to repair critical infrastructure and help displaced families return to their homes (or find new ones). As of October 12, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) had approved $441 million in assistance for individuals affected by Helene and over $349 million in public assistance funds to help rebuild communities. That’s more than three-quarters of a billion dollars, before factoring in the assistance for victims of Hurricane Milton.

These are impressive figures and demonstrate the nation’s capacity to respond to major disasters. But the number of such calamities will grow as climate change accelerates, and FEMA’s budget and resources are not limitless. On October 2, between Helene and Milton, Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas said that FEMA lacked sufficient funding to provide emergency relief if more superstorms hit the country. “We are meeting the immediate needs with the money that we have,” Mayorkas told reporters as he traveled to storm-ravaged areas to meet with local officials. “We do not have the funds, FEMA does not have the funds, to make it through the season.”

Congress is expected to pass a supplemental appropriation to refill FEMA’s coffers when it reconvenes after the November election, but the 2024 funding crisis provides a preview of a time in the not-too-distant future when the federal government will be hard-pressed to finance recovery efforts in every storm- or fire-ravaged region. The result will be mass migrations of US “climate refugees” (think of the “Okies” from the 1930s Dust Bowl phenomenon) and possible internal unrest.

For more than a century, we have been taught that national security—widely considered the most sacred duty of our top officials—entails the defense of our allies and overseas interests against hostile powers. This outlook has proved fabulously beneficial to US arms manufacturers, who have received trillions of dollars in Pentagon contracts for weapons designed to overpower those so-called hostile regimes. It has also smoothed the rise of many opportunistic politicians, who have chided their opponents for failing to adequately promote national security. As this assessment of Helene and Milton’s impacts has demonstrated, however, this conventional notion of national security is woefully obsolete: It fails to account for the most immediate and potent threats to the country.

From now on, any assessment of the threats to US national security that professes to be based on observable fact must portray climate change as posing as great a peril as do conventional military threats—and the threat from climate change is growing faster than any of those other dangers. A failure to acknowledge this will leave the nation unprepared for the deaths, disasters, and dislocations to come. At the same time, recognition of global warming as a major threat to US security will require major changes in policy, including a substantial shift in funding and resource allocation from war fighting to climate-change mitigation and adaptation.

Once the exclusive preserve of Republicans and defense hawks, the vocabulary of national security should now be appropriated by those of us who can foresee the impending consequences of climate change and seek an all-out national drive to halt its advance. If there is one thing that we can be certain of, it is that the climate crisis will invade our borders again and again, with ever-increasing fury—and we are not prepared for its onslaught.

Michael T. KlareTwitterMichael T. Klare, The Nation’s defense correspondent, is professor emeritus of peace and world-security studies at Hampshire College and senior visiting fellow at the Arms Control Association in Washington, D.C. Most recently, he is the author of All Hell Breaking Loose: The Pentagon’s Perspective on Climate Change.