The Insurance Crisis Looming in California as the Wildfires Burn

California’s Department of Insurance has worked to repair the broken insurance system, but the LA fires threaten to undo the progress the state has made.

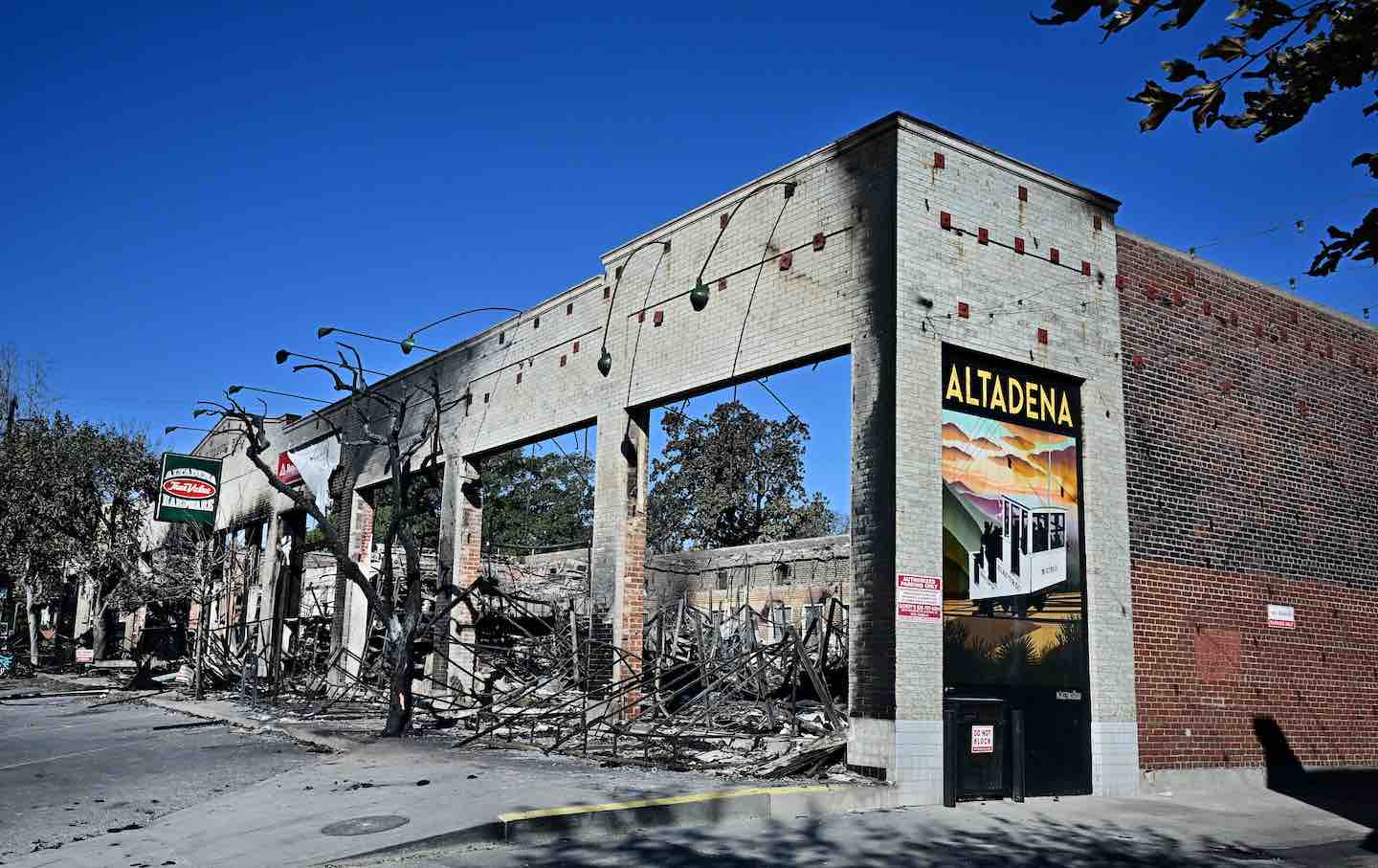

The burnt remains of a building where once stood a hardware store are seen in Altadena, California, on January 15, 2025. The historic community of Altadena, on the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains, has been left in ashes and rubble though some homes remain standing.

(Frederic J. Brown / AFP)

Last week, a rare winter firestorm, whipped to apocalyptic proportions by near-hurricane force Santa Ana winds, and made worse by the fact that Southern California has had a shockingly dry winter, swept out of the mountains and into several Los Angeles communities. These included the affluent coastal community of Palisades and the historically African American neighborhood of Altadena, an hour’s drive to the east, at the base of the Los Angeles National Forest. Over the course of hours, as the winds carried embers from one community to the next, tens of thousands of Los Angelenos lost their homes.

What remains in the Palisades and Altadena is a cross between Dante’s Inferno and the Somme. Things that don’t normally melt melted. Things that aren’t usually reduced to ash were so reduced. Altadena and the Palisades lost a number of their schools, their grocery stores, their banks, their cafés, and their restaurants and bars. Entire economic and cultural ecosystems, nurtured over decades, were burned out of existence.

More on the LA Fires

Dozens were killed by the flames and smoke; tens of thousands of Los Angelenos lost their homes and businesses; hundreds of thousands more had to be evacuated; and untold billions of dollars of damage—the exact amount likely won’t be known for months—was inflicted on a state that for years has been reeling under climate-change-related disasters and property and fire insurance systems that have reached something close to a breaking point.

Over the last couple years, California’s Department of Insurance has worked at repairing this broken system, putting in place new regulations that allow insurers to use forward-looking catastrophic modeling in asking for rate increases—and, in exchange, requiring those insurers to significantly raise the number of policies they write in areas that they have fled in recent years. According to department press secretary Gabriel Sanchez, those regulations kicked in at the end of 2024 and were, at least until this recent disaster, expected to start delivering more insurance options for customers by the middle of 2025. “Our goal is to have more companies writing more policies, to stimulate competition,” Sanchez says.

The LA fires threaten to undo whatever progress they made.

On the ground, concerns about insurance mingle with more immediate worries about surviving the flames. Fifty-four-year-old William “Joey” Galloway, a longtime Altadena denizen and businessman, lost a commercial building on East Mariposa Street, which his father had bought back in the 1980s, but he says at least he had insurance on the building. “State Farm and all the big companies won’t do it,” he explains, in a strong basso voice, about the nonrenewal he faced after the building’s previous policy expired. “It’s some little company.” He can’t remember the name of the new insurer, but he says it’s a good policy and that he was able to file a claim a day after the fire destroyed his building.

He leases out the building to seven local businesses, including the Amara Kitchen, which had opened to great acclaim several years ago and was part of an economic revival movement in the community. Around back, in the alley behind his lot, which he named Mariposa Junction, Galloway had recently started hosting a series of community events, at the request of the local chamber of commerce. There was a night market for local artists during the summer, and a “Sip and Shop” fundraiser for the chamber in December.

When Galloway drove into the neighborhood last Wednesday to see the damage and scope out his buildings, he recorded on his cellphone a shocking scene of flames, smoke, and rampant destruction. It was daytime, but the smoke was so intense it might have been the middle of the night. His building had been reduced to a shell, he says, and the alleyway behind it was devastated.

Galloway’s situation of facing a nonrenewal from his insurance company is similar to that of tens of thousands of other Californians. Large carriers such as State Farm, Allstate, USAA, and Travelers have turned away increasing numbers of existing customers and have also stopped accepting new property insurance applications from Californians. Many of those customers, including some in the Palisades area, have, in consequence, signed up with smaller, less pedigreed insurers—companies that Sanchez says are out-of-state operators not subject to California’s regulations—or they have had to fall back on the state’s last-resort fire insurance program, the FAIR Plan, which now covers close to half a million California homes.

As nonrenewals have accelerated, demand has skyrocketed for FAIR, which the state set up to assist homeowners who were otherwise unable to get coverage due to the growing number of weather-related disasters and wildfires. The program is funded by a pool of money required from private insurance companies, but typically has premiums that are higher than traditional private insurance, as well as higher deductibles, and it covers fewer extras, such as the full cost of relocation during the months or years in which a building or home is rebuilt.

Galloway has, so far, managed to avoid using FAIR. His family trust owns and manages 12 residential properties, none of which had their insurance policies renewed over the past year. Eight of those policies ran out on January 1 of this year. Thankfully, after considerable time and effort, he succeeded in getting new policies written, at a far higher price, on seven of the buildings. “My rates went up three times,” he says. For the eighth, however, a 25-unit residential building, he had not yet managed to find a new carrier willing to cover him when the fires erupted. Had that building gone up in flames, the result would have been financially devastating for the Galloways; it would also have resulted in a huge crisis for the renters whose homes would have been lost.

For years, elected officials and consumer advocacy groups like the Consumer Federation of America, which has promoted consumer rights since the late 1960s, have been pressing insurers to integrate climate risk into their insurance planning. They wanted insurers to build up more reserves for disasters, and they believed that in an era of climate change everyone would benefit if the insurance industry lobbied to put the brakes on housing development in areas particularly at risk for fires and floods. Instead, insurers turned a blind eye to the growing risks, seeking to take in as much profit as they could for as long as they could. It was a somewhat similar situation to the subprime home-loan market in the years leading up to the 2008 crash. “They kept their heads in the sand,” CFA director of insurance Doug Heller argues. “They ignored it, knowing if they ever felt the risk they could just walk away,” since they only provide insurance on a year-by-year basis.

Now, insurers are belatedly waking up to the risks of rampant climate change—much as lenders woke up, too late, to the risks of the sub-prime market in 2008—and their response has been to abandon high-risk areas, despite the fact that these same regions have been extremely profitable for the industry over the last few decades. State Farm alone has built up a $140 billion surplus in recent years that, the Consumer Federation and other groups claim, ought to allow it to pay fire victims without further destabilization of the market. And the National Association of Insurance Commissioners recently found that America’s insurance industry was, collectively, sitting on an “all-time high” surplus of $1.14 trillion.

And yet every new natural disaster has the insurance industry predicting a market collapse and arguing for increased rates and deregulation. Making matters worse for California, and compounding the financial damage of disasters, the Los Angeles fire crisis comes just before President-elect Donald Trump’s inauguration and the looming threat that his administration will withhold federal emergency funds or add conditions to such funding to punish the state for its leadership’s opposition to extremist MAGA policies such as the mass round-up of immigrants.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The scale of California’s insurance crisis can be seen in the numbers. Just in 2024, State Farm announced that it would not renew policies for 30,000 homeowners in the state, including more than 1,000 policies in the Palisades. Other companies were engaged in a similar pull-back exercise, often raising premiums astronomically because of the threat of climate disasters, only to then hold onto those profits by refusing to reinsure people in high-risk areas.

To try to rein in this chaos, California Department of Insurance commissioner Ricardo Lara has pushed significant reforms to Prop 103, the 1988 proposition that set up the modern insurance market in California and limited the rate increases that insurers could impose on customers. Prop 103 mandated that insurers use the past 20 years’ history in calculating risk and thus setting premium fees; Lara proposed allowing insurers, in an age of rapid climate change, to instead use forward-based models, predicting how risk would change in the future. The result would let insurers charge more. In exchange, Lara got the insurers to agree to provide more coverage in hard-to-cover areas, and to reward clients who made a good-faith effort to “harden” their homes against fires, through putting in new roofs and other changes, with lower premiums.

Lara’s hope is that, in bringing competition back to the insurance market, rates eventually will, for many consumers, start to drop once more, especially as more communities and individual homeowners harden their properties and land against fires. In a best-case scenario, it will, however, likely take years for the market to fully stabilize—and last week’s firestorm will only make the process more difficult, given the extent of the damage and the costly insurance payouts that must follow.

True, this isn’t a problem in any way unique to California, with its fires, its floods, its droughts, and its windstorms—not to mention the perennial, non-climate-related issue of earthquakes. Florida’s insurance industry is also in crisis, with rates soaring; Texas’s system is a mess; North Carolina’s is facing a reckoning after recent hurricanes, as are state systems dotted around the country. In fact, while fires tend to grab the headlines, insurance companies pay out a higher percentage of claims to victims of wind and hail damage in the Midwest than they do to fire victims in California.

Recognizing that this was a national issue, then-Representative Adam Schiff put forward a bill last year that would have done for the property insurance industry what the Affordable Care Act did for the health insurance industry: prohibit companies from refusing to insure customers based on the equivalent of preexisting conditions, and disallow the practice of cherry-picking customers so as only to have to cover those least likely to use insurance services. But the bill went nowhere. Now, with the GOP in charge of the White House and both houses of Congress, it is even less likely to gain traction.

As a result, efforts to protect consumers and rebuild stable insurance markets in an era of climate catastrophe are falling to the states. And even states with the muscle of California are fighting an uphill battle. “You’ve got this combination of things colliding all at once,” says an official with the state’s Department of Insurance. “Every insurance company is making decisions in a vacuum, and there’s chaos.”

The fires haven’t just hurt property owners. They are also causing huge upheaval for renters, many of whom lack adequate insurance. Galloway’s friends 28-year-old Josef Larry, Josef’s cousin Kevin, and his mother are among the uninsured. In the pre-dawn hours last Wednesday morning, the flames suddenly roared off of the mountainsides and into the populated areas of the flats. Josef’s family had minutes to evacuate their rental home. In the end, they managed to save their pet dog and the clothes on their back. Everything else was lost to the inferno. The family had no renters’ insurance, and now they have been left with nothing.

“The more days go on, the more I feel that sock in the stomach settling in,” Larry, who runs his family’s floor-finishing business, Larry’s Hardwood Floors, explains. “I had no renters’ insurance. I had it on my list [to do] but never did.” While he had liability insurance for his business, he didn’t have property insurance to cover his tools. As a result, between his personal property losses and his business property losses, Larry says that he “lost everything, down to my grandfather’s passed-down rifles, my machines, my wood and materials, my nails. Everything.”

The Department of Insurance says that it is aware of the crisis now confronting renters, but there isn’t yet a statewide policy in place to respond to this. Instead, says Gabriel Sanchez, renters should contact the department and its staff will try to assist them, on a case by case basis.

It’s a mind-warping situation for these renters to be in. “Terrified is an understatement,” Larry says. “I have to start from zero.” Temporarily living with relatives in the suburb of Ontario, he hates the feeling of being a burden on others. “It’s something I have as a man,” he says. “I need to figure it out. I’m more of a giver. I don’t feel comfortable taking. I’d rather work for my money than have someone giving it to me.”

Support independent journalism that exposes oligarchs and profiteers

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation