It’s Time to Rethink Everything About How We Fight Fires

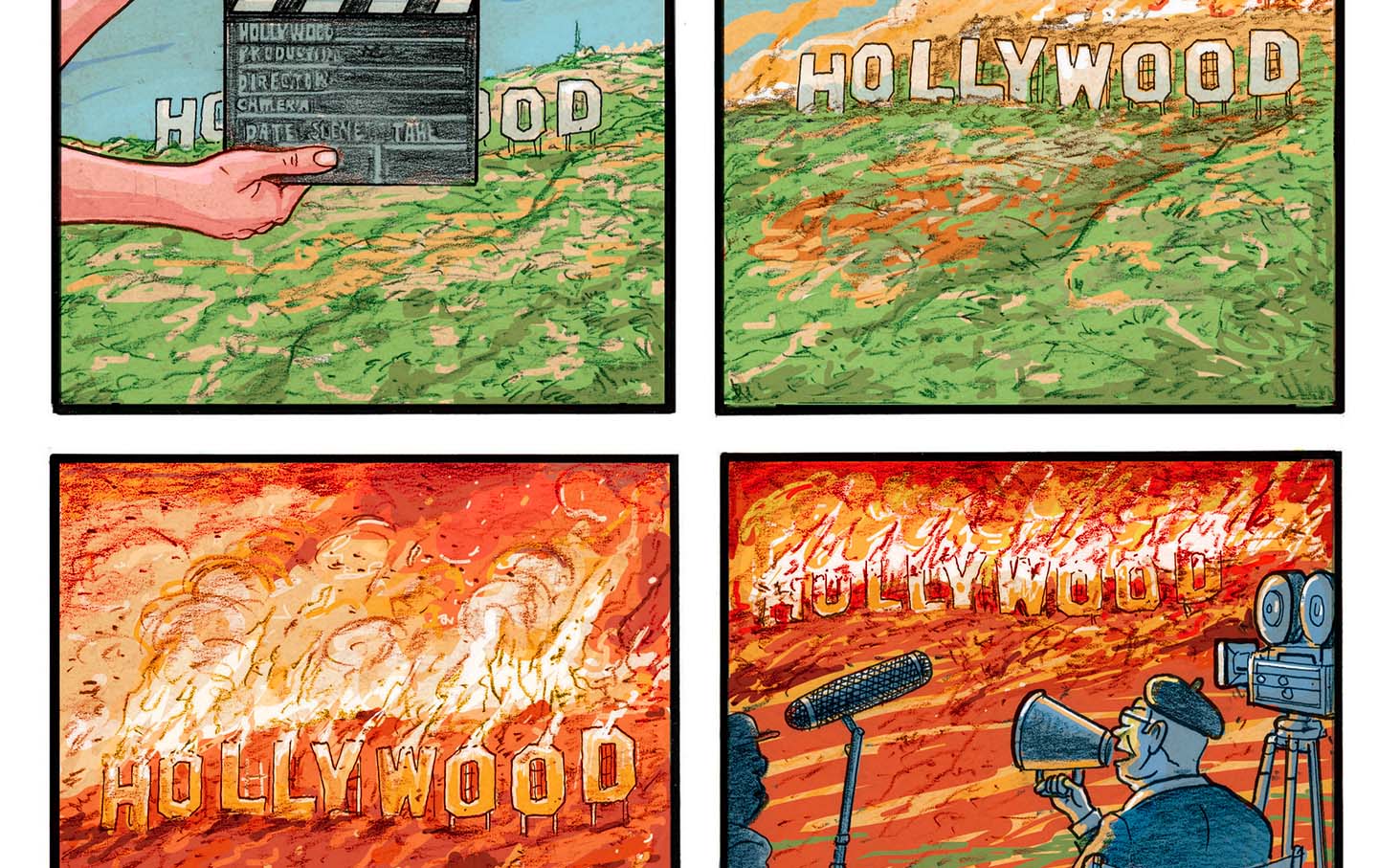

The LA disaster is a wake-up call: Our firefighting playbook was written for a world that no longer exists. We need a new approach, and we need it now.

A firefighter monitors the spread of the Auto Fire in Oxnard, northwest of Los Angeles, California, on January 13, 2025.

(Etienne Laurent / AFP via Getty Images)On January 5, anticipating stronger than usual Santa Ana winds after a prolonged drought, the state of California requested that federal and state firefighting resources be “prepositioned” to respond to wildfire incidents in the Los Angeles area. The next day, atmospheric scientists noted the dangerous combination of winds, low humidity, and unstable atmosphere that creates extreme fire weather. All that was needed for a catastrophic, uncontainable wildfire to spread was a spark.

On January 7, firefighters responded to reports of a brush fire near Temescal Canyon, North of Pacific Palisades. The parched Chaparral, crowded by flammable non-native species, exploded in flames and sent embers into the air. Gusts nearing 100 mph carried those embers more than two miles and grounded aircraft during the critical window when the fire might have been small enough to control.

We know what happened next. The fire spread relentlessly; as I write, the Palisades, Eaton, Kenneth, and Hurst fires have burned more than 40,000 acres and 12,000 structures combined, and Palisades—the largest—remains less than 20 percent contained. The death toll is in the dozens and likely to rise. Tens of thousands have lost their homes, upending the geography of their lives. Around 100,000 people are currently displaced. It remains to be seen whether California’s insurer of last resort will have the funds to protect many of those families from further destruction. When the wind does calm, it will take years for the region to recover.

The national media response to the fires was swift: The world watched as bulldozers pushed aside abandoned cars on I-405 to let firefighters in, and celebrities spoke of watching their homes burn. Viewers and social media users saw houses go up in flame, and photographers captured apocalyptic scenes of heroism and heartbreak. Pundits and politicians traded barbed comments about climate change, climate denialism, Democratic leadership, budgets, responsibility, and blame. Everyone doubled down.

Merely adapting to changing conditions has brought us to where we are today. Government spending on fire suppression sets and breaks records nearly every year. Wildfires that burn too intensely and in the wrong season threaten hundreds of thousands of homes and millions of acres of land. Firestorms raze communities and take lives. Budgets ratchet up again, only to be eclipsed by further need. We have entered the acute phase of a fire crisis long in the making, and reactive adaptation will continue to leave agencies struggling—and failing—to keep up with the chaos.

As a wildland firefighter who has studied and worked in land management policy, I know that fire is not a disaster but a condition—a basic chemical reaction that responds to immediate environmental factors. The loss of life and destruction of livelihoods are disasters. Increasingly, fire incidents like those in LA escape definition as thoroughly as they escape control. FEMA’s US Fire Administration chief Lori Moore-Merrell told The New York Times last week, “There isn’t a fire department in the world that could have gotten in front of this.” It’s true: “This” was an unfightable fire. No amount of money spent on fire crews, equipment, and response could have stopped the Palisades fire once it had reached just a few acres. We cannot buy back more than a century of mistreatment of the land and changes to the atmosphere. We’re responding to fires using a playbook written for a world that no longer exists. To move forward, away from these firestorms, we have to do more than tweak a few tactics. We have to change the way we think about fires—and not just about fighting them. That starts with changing the way we think about our relationship to nature, and to fire itself.

Wildland firefighters in California and across the country, myself included, are trained to fight fire in a range of fuel types, from grass and brush to dense forests to the Wildland Urban Interface, the official term for the places where nature and humanity meet. The latter has recently received increasing skepticism, and for good reason: It presumes that human-inhabited areas can be defined in stark contrast to uninhabited zones. In fact, inhabited and uninhabited areas form separate but closely linked components of the same ecosystems. When those ecosystems burn, the fire does not respect zoning boundaries, town limits, or the edges of parks and preserves.

I’ve seen destructive wildfires up close. Last summer, in Oregon, I was part of an engine crew responding to a fire that had grown to more than 100,000 acres. As we struggled to hold a line and drew down water reserves to prevent the fire from taking hold in the dry grass and trees behind us, torching trees and buildings lit the night orange against a black sky. That fire would become Oregon’s longest-running blaze of 2024, burning until the end of the regular fire season. But by October, my crewmates and I were back to our regular lives: Our season had ended. As seasonal employees, we expected nothing less. Most wildland firefighters work only in the late spring, summer, and early fall, when fires are most common. Until the last decade, staffing firefighters through the winter made little economic or logistical sense. Firefighters put fires out when they’re burning. Western fires, except those in increasingly common drought conditions, usually burn in the summer. The fire in Oregon burned more than 150,000 acres and destroyed just a few homes, prompting a choreographed response by local, state, and federal agencies. The outliers, like the LA fires, can be more destructive, more sensational, and more apocalyptic than many of the megafires our institutions are prepared for.

But the West’s fire season keeps starting earlier and lasting longer. Today’s outlier could increasingly be tomorrow’s norm. When firefighting resources and tactics become overrun, as they have been in LA, we must be willing to accept that the reason is not as simple as budgets, climate change, short-term management failures, or development practices alone. It’s all of those combined, joined together by the beliefs that underlie them.

The Palisades firestorm reminded many of similar catastrophes in Lahaina in 2023 and Boulder in 2021: wind-driven suburban catastrophes that claimed lives and destroyed dense communities in minutes or hours. These events, so different from most wildfires, reveal something about our cultural attitude toward fire. We see it as a destructive force to be mitigated, a natural phenomenon that management practices can attenuate or even eliminate—a harm that can be prevented. In these deadly storms, those views aren’t wrong. But they are incomplete.

The US government interacts with fire mostly in the name of preventing it. In 2024, the Forest Service and Department of the Interior combined spent more than $4 billion on wildfire suppression, and a little more than $700 million on preparedness. Fire management is based on putting fires out when, as fire managers say, “values [are] at risk.” Values like human lives, infrastructure, marketable timber, and cultural resources like scenic areas.

But there’s another way. After all, Southern California’s ecosystems evolved alongside human-stewarded fire. The removal of Indigenous people who used fire to manage biomass and regulate biological processes, and the suppression of incidental fire since the late 19th century, has stockpiled unburned fuel. Changing weather patterns as a result of climate change increase drought conditions and make wind less predictable. More variable rainfall causes excess plant growth some years; then, drought dries it out, making it flammable the next. Only in the last few years have these effects become obvious to the casual observer. The proliferation of homes in fire-dependent and recently fire-excluded environments, too, has made communities vulnerable to less predictable, more impactful fire.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →While overstocked fuel, climate-change-driven weather patterns, and vulnerable flammable development are often treated as separate and compounding issues, they each rely on our belief that our physical environment can and should be controlled, rather than inhabited and cared for. All three issues are a part of the same backward understanding of the human role in managing ecosystems that has plagued the West since the start of colonization. For centuries now, humans have dominated the landscape, extracted resources, and developed housing and infrastructure where it was most convenient. Now, our façade of control is slipping away. Reaching stability, and preventing further disaster, will not come from adapting to a “new normal” but from acknowledging our role as a keystone species in a fragile array of long-derelict ecosystems finally regulating, violently, by fire.

Changing a few management practices won’t get California out of the mess it’s in right away. For years, firefighters will remain outgunned by the momentum of several centuries of policy failure. But the glaring unnaturalness of natural disasters, as we saw in North Carolina last year, is beginning to crawl its way from coast to coast. Millions of lives are at stake. Accepting responsibility for the health of systems so much larger than ourselves is only the beginning of reclaiming humans’ place as keystone, not king, in the biological order. As these firestorms have so violently shown, we may not have a choice.

More from The Nation

How Journalists Can Stand Up to Trump’s Bluster How Journalists Can Stand Up to Trump’s Bluster

Newsroom layoffs make it harder, but reporters must keep telling the truth about climate change.

The People in Charge Won’t Save Us From Climate Catastrophe. We’ll Need to Do It Ourselves. The People in Charge Won’t Save Us From Climate Catastrophe. We’ll Need to Do It Ourselves.

Grassroots efforts in places like North Carolina show what we can—and increasingly must—do in a world plagued by climate disasters.

Trump Is Hitting the Gas on Our Path to Planetary Destruction Trump Is Hitting the Gas on Our Path to Planetary Destruction

The planet’s decline is already deeply underway. Trump’s clearly about to lend it a remarkably helping hand

Climate. ACTION! Climate. ACTION!

California Fires Fossil Fueled By The Oil Industry.

How the Wildfires Could Reshape the Climate Movement in California How the Wildfires Could Reshape the Climate Movement in California

As the city debates how it can best address the impacts of increasingly devastating natural disasters, organizers hope to seize the moment.