Maine Is in an Epic Battle Over Its Future

Voters could turn two private utilities into public goods. The corporations are fighting it tooth and nail.

There’s a moment in the ocean twice daily when it’s hard to read the flow of the water, and you can’t quite tell whether the current is going in or out. Mariners call this “slack tide.” While the name implies idleness, that’s not what’s really happening. There are big, opposing forces at work beneath the surface, and they are going to send the tide in one direction or the other very soon.

Politics in Maine has felt like a slack tide recently, especially around issues of climate and energy. Opposing forces of progress and regression are churning away at each other. The main fight centers on a November ballot measure that would turn the state’s private utilities public. If that happens, it would be a huge step toward dealing with the climate crisis, and a model for other states.

It’s easy for outsiders to forget about Maine, off by itself in the corner of the map. But it’s one of our most politically interesting states. Beyond its idiosyncratic electoral decisions—this is the state that once had the racist Republican former governor Paul LePage, the supposedly “moderate” Republican Senator Susan Collins, and the independent, Democratic-aligned Senator Angus King serving at the same time, though thankfully Mainers seem to have tired of LePage’s antics for good—it has a first-in-the-nation public financing scheme for candidates that lets a wide variety of people into the political pool, and a ranked-choice voting system for federal office that keeps third parties from being spoilers.

All those forces will be at play in November’s referendum, when voters must decide whether they want to turn the state’s two big private electric companies—Central Maine Power and Versant—into Pine Tree Power, a nonprofit, publicly run utility.

The two corporations sent $187 million in profits out of Maine last year—much of it to shareholders in such far-flung places as Qatar, Norway, and Canada. That’s serious money—and if it weren’t being sucked out of the state, the advocates of Pine Tree Power argue, Maine could lower rates by an average of $367 per household per year, which would mean shutting off fewer customers (nearly 10 percent of the state’s residential customers got disconnect notices last spring).

Moreover, with cheaper borrowing costs than the 10 or 12 percent return on equity that private companies demand, a public utility would be better prepared to build out the larger electric system that Maine will require as its residents give up oil furnaces and gas cars in the ongoing green transition. (The incumbent utilities are so ambivalent about renewables that Central Maine Power had to pay a $700,000 settlement for slow-walking the solar transition.) “We believe [utilities are] a direct way of targeting the fossil fuel industry,” Candice Fortin, the US campaigns manager for the climate group 350.org (which I helped found), explained recently. “Returning power to the people and looking for big fights is where we can best show solutions and also resist the fossil fuel infrastructure.”

Mainers care about climate change. The Gulf of Maine—the heart of the state’s fishing industry, and also much of its identity—is warming faster than almost any body of water on the planet. But that concern could be drowned in the nor’easter of commercials and mailings that the utilities are producing. As of this writing, they’re outspending public power advocates 32 to 1 and have dropped $27 million into the kitty—an extraordinary sum in a state with less than 1.5 million residents. (Though considering the aforementioned millions in profits they extracted from the state, confusing Maine voters is worth a good deal of money to them.) They’ve hired the Obama veterans who run Left Hook Strategy, as well as the Global Strategy Group, which last year tried to help Amazon crush a union drive at a Staten Island warehouse. The utilities have also created front groups like Maine Affordable Energy, whose executive director, Willy Ritch, said he didn’t think Mainers wanted “out-of-state politicians” telling them what to do; reporters pointed out that his group had taken $18 million in out-of-state money to oppose the referendum.

Bernie Sanders has been helping the Pine Tree campaign. “Power belongs in the hands of the people, not greedy corporations,” he declared.

The endless onslaught of anti-public-power TV ads may carry the day, but there’s not much else on the ballot, so turnout may be low, and there’s no question that the Pine Tree Power advocates are committed, disciplined, and creative.

There are also signs that the tide may have begun to turn decisively on climate issues in Maine. In July, the Legislature passed a law that should ease the way for a large-scale build-out of offshore wind power in the state’s Atlantic waters. Maine has enough wind to supply far more than its own needs; if it ends up selling power to other East Coast states, “the workers who are constructing these could be building a turbine or two every month for the next 30, 40, 50 years,” said Jack Shapiro, the climate and clean energy director of the Natural Resources Council of Maine.

But passing the law was no sure thing; offshore wind power has been stymied in the state in the past, largely because of opposition from fisheries interests worried that the turbines might interfere with fish stocks. And since the Maine Lobstering Union is affiliated with the state AFL-CIO, that was enough to keep organized labor on the sidelines.

Beginning in January, though, members of Maine’s labor community began meeting with fisheries groups, arguing that the gusher of money in the Inflation Reduction Act made it in the best interests of everyone to strike a deal. Fishermen wanted the wind turbines pushed farther offshore and the number of power cables minimized; with some of those elements in place, and with union wages guaranteed, the state AFL-CIO agreed to sign off on the plan.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Unions representing the building trades have often been foes of environmentalists, but that dynamic may be changing elsewhere, too. In states such as Illinois, New York, Rhode Island, and Texas, climate activists and unions have begun negotiating over similar kinds of pacts.

Still, the status quo bias of labor unions sometimes can’t be overcome: The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers—and hence the Maine AFL—is siding with the bosses in opposing Pine Tree Power on the grounds that if workers were classed as public employees, they might lose the right to strike. Advocates for the public utility insist they’ve included language in the proposal that requires the elected board to contract out to a private operator, allowing the union to maintain that right.

As I said, slack tide. But slack tide never lasts more than a moment. Soon it’s flowing hard one way or the other. And Maine has the highest tides in the Lower 48.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

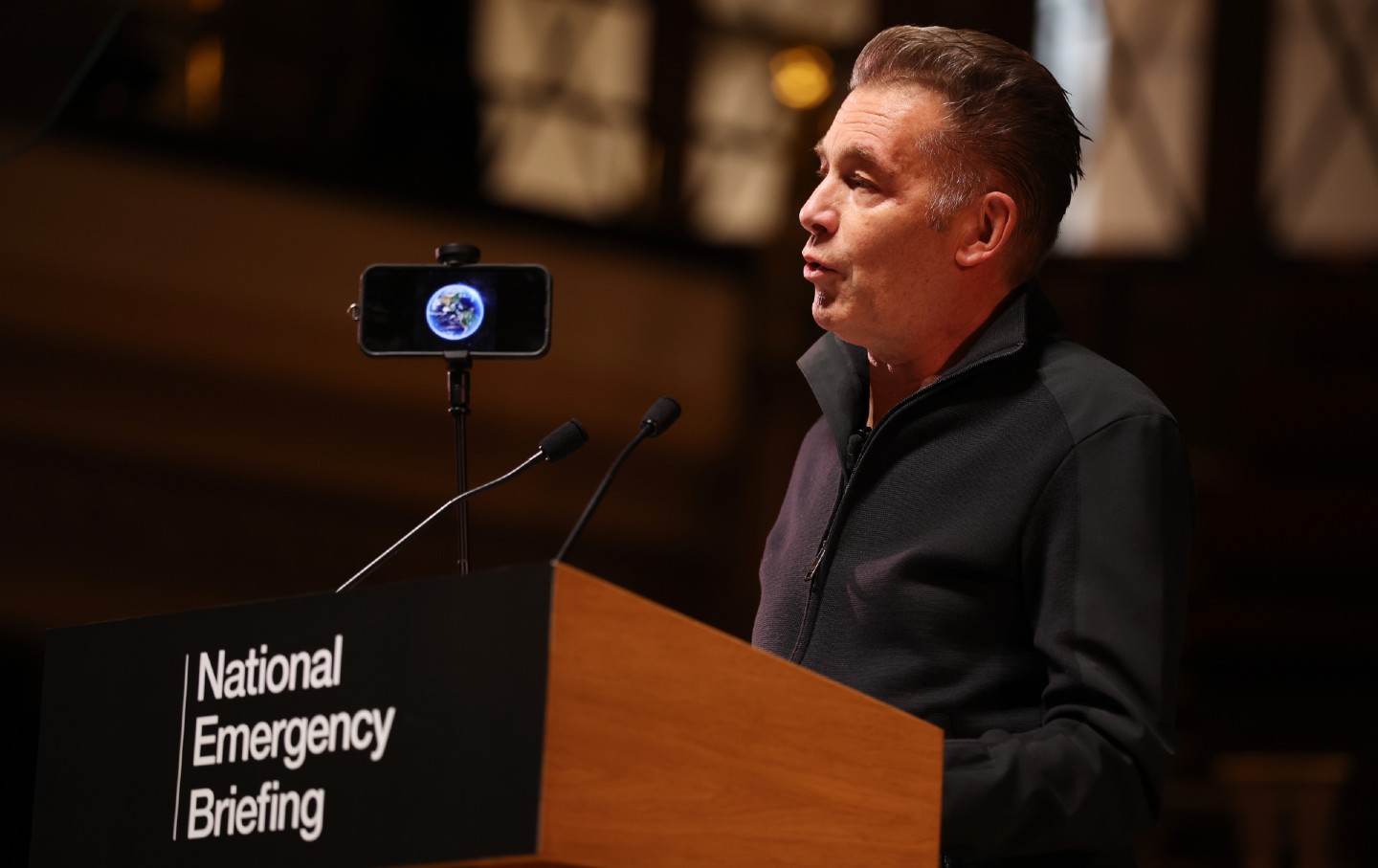

The UK’s Climate National Emergency Briefing Should Be a Wake-Up Call to Everyone The UK’s Climate National Emergency Briefing Should Be a Wake-Up Call to Everyone

The briefing was a rare coordinated effort to make sure the media reflects the science: Humanity’s planetary house is on fire, but we have the tools to put that fire out.

AI Will Only Intensify Climate Change. The Tech Moguls Don’t Care. AI Will Only Intensify Climate Change. The Tech Moguls Don’t Care.

The AI phenomenon may functionally print money for tech billionaires, at least for the time being, but it comes with a gargantuan environmental cost.

Backsliding in Belém Backsliding in Belém

Petrostates at COP30 quash fossil fuel and deforestation phaseouts.

Wake Up and Smell the Oil. Your Nation’s Military Is Hiding Its Pollution From You. Wake Up and Smell the Oil. Your Nation’s Military Is Hiding Its Pollution From You.

A fact all but ignored at COP30.

Trump Promised to Bring Back Coal. This Town Listened. Trump Promised to Bring Back Coal. This Town Listened.

Through executive orders, Congress, and a loyalist cabinet, the Trump administration has delivered big for enclaves of coal country like Colstrip, Montana. But how long can it las...

China Is Now the World’s Climate Champion China Is Now the World’s Climate Champion

The news out of COP30 does not engender much hope, but China’s embrace of renewable energy shows that climate protection makes smart economic sense.