A Toxic Legacy of Mining In Peru

Centuries of environmental exploitation in the small town have ensnared its inhabitants in a vicious cycle of displacement, irreversible health damage, and social conflict.

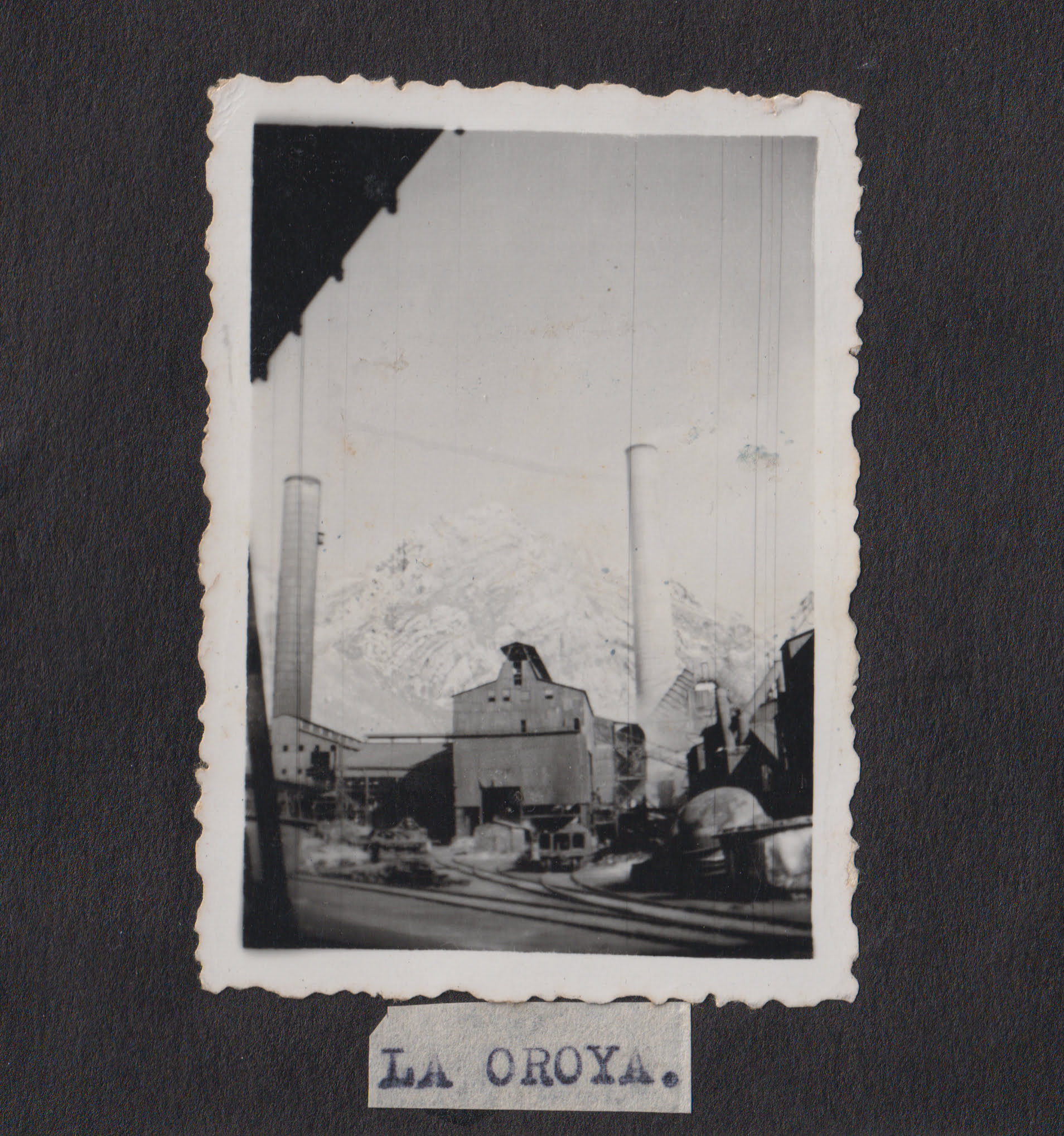

In 1982, at Chulec Hospital in the Peruvian city of La Oroya, my great-grandfather, Demetrio Cárdenas, passed away. The doctor diagnosed that the cysts were a result of his 35 years of work in the lead processing furnaces of the mining complex. Despite this diagnosis, the state mining company Centromin Perú never took responsibility. The case of Demetrio Cárdenas is just one among thousands affected by heavy metals since the opening of the metallurgical complex in La Oroya in 1922.

La Oroya is a small town located at 4000 meters above sea level, in the depths of the Peruvian Andes, where my mother was born and where both my grandfather and great-grandfather worked as miners in one of the most polluted cities in the world.

This town is the capital of the Yauli province, with a mining history dating back to 1761. Centuries of mining activity have left a toxic legacy that has ensnared its inhabitants in a vicious cycle of displacement, landscape mutilation, environmental pollution, irreversible health damage, and constant social conflict between those dependent on mining as their sole source of income and those who see it as a deadly threat due to the high levels of heavy metals in the air they have breathed for decades, hindering the development of other economic resources.

“In La Oroya, we have seen adults and children fade away like a candle, with no hope of life,” says Yolanda Zurita Trujillo, a native of La Oroya and a former worker at the metallurgical complex.

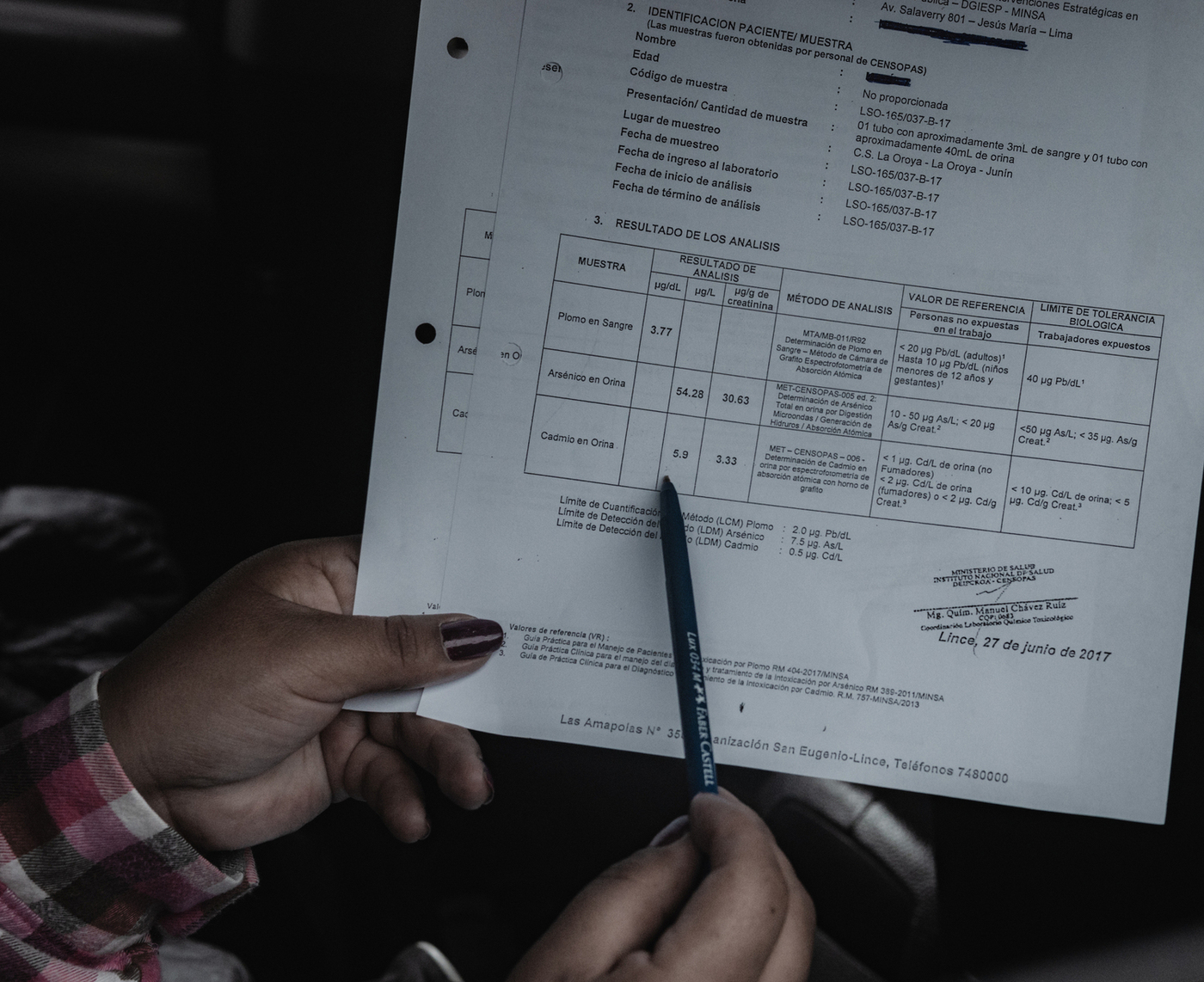

At an early age, she and her father, Epifanio Zurita, a miner, saw their health deteriorate due to toxic gas emissions. Yolanda, along with her mother Victoria Trujillo, has dedicated her life to environmental activism, leading the demand against the mining company Doe Run Peru, owned by the Renco Group. Despite constant threats from those who yearn for the economic boom years that mining brought to La Oroya, Yolanda persists in her struggle.

Nowadays, the mining legacy that has deeply marked this land persists a few kilometers from La Oroya, in the desolate ruins of the ancient city of Morococha. Six families resist in solitude the displacement of the slopes of what used to be the Toromocho mountain. In just 14 years, the company Chinalco Peru has erased the mountain, leaving only a deep pit for copper extraction that continues to grow and pollute the air with dust containing metals, a result of the constant daily blasts executed by the mining company.

Here, where a mountain once stood, where there were towns and a vibrant life, everything has been altered by the extractive activities of foreign companies.

Just weeks ago, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights condemned Peru for neglecting to regulate the La Oroya mining complex, ordering the country to compensate for environmental damage and provide free medical care to victims.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation