Meet the Young Peruvians Fighting in Court for Climate Action

Seven youth plaintiffs, ages ranging from 14 to 16, argue that the state is violating their right to a healthy environment by failing to curb Amazon deforestation and mitigate climate change.

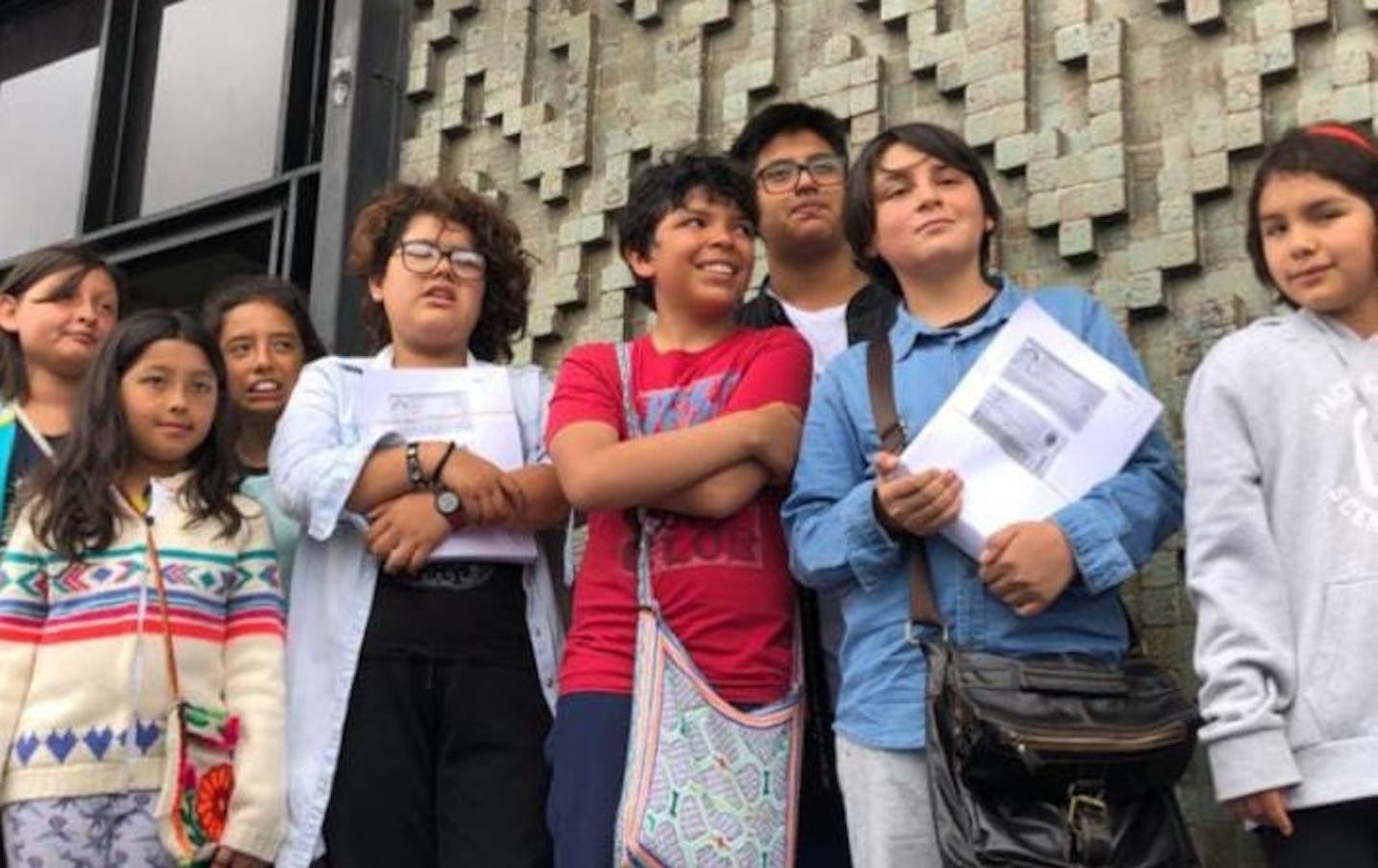

The Álvarez youth plaintiffs stand outside of the Judicial Branch of Peru: Superior Court of Justice of Lima after filing their legal complaint against the state in the judiciary.

(Legal Defense Institute)Héctor Enrique Delgado Pérez was only 10 years old when Perú experienced one of the strongest El Niño events in its history. The consequences were particularly striking in Cantagallo, an Amazon Indigenous urban migrant settlement threatened by increased flooding from the nearby River Rímac, where Delgado Pérez’s activist lawyer mother often brought him. Meanwhile, near where Delgado Pérez lived in Lima, many faced water scarcity. At his school, which is named after José Antonio Encinas and promotes a nontraditional approach to education, he learned about the climate crisis’s role in intensifying the effects of weather phenomenon. “We felt powerless to change something that was affecting all of us at this moment,” he recalled of his conversations with classmates in 2017.

Moved to action, Delgado Pérez joined a boundary-breaking legal case coordinated by a peer’s father, Legal Defense Institute attorney Juan Carlos Ruiz Molleda, who was inspired by his two young daughters (also plaintiffs) and a similar case in Colombia.

Now, amid yet another year of stronger El Niño effects and record-breaking heat, Delgado Pérez is one of seven youth plaintiffs, ranging in age from 14 to 16, in Álvarez et al v. Peru. Many of the plaintiffs have entered their teens since filing their case in 2019.

After their virtual hearing in July, there is still no clear timeline for ruling. The plaintiffs claim that by failing to curb Amazon deforestation and mitigate climate change, the state is violating their rights to life, water, health, and a healthy environment. Among the actions they seek through a court order is a concrete plan from the state for achieving net-zero deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon by 2025; for regional governments to form related plans, incorporating climate adaptation and mitigation measures; and for the state to halt deforestation on public lands.

Today, as Delgado Pérez and his peers eagerly await a ruling, the growth of the Fridays for Future movement and the momentum of youth-led and human rights-based climate change lawsuits worldwide provide renewed hope for their four-year-old case. Most recently, US youth plaintiffs saw historic success when Montana’s refusal to consider climate change impacts in permitting fossil fuel projects was deemed unconstitutional in Held v. State of Montana.

Yet the young Peruvians face unique obstacles in their fight for a stable climate in a Global South country. While raising key considerations around intergenerational justice, the Álvarez case also highlights questions of fairness concerning countries’ obligations to curb emissions and conserve natural resources. How the case unfolds could have repercussions for future climate litigation and political action both within and beyond Peru.

An Opportune Moment to Revitalize their Case

For many young people growing up in a world of extreme heat, ferocious natural disasters, and rapidly melting glaciers, the threats posed by climate change, including the rights to life and health, are glaringly obvious. Yet the successful use of strategic litigation to establish clear mandates for governments and companies to acknowledge these risks, and accordingly take climate action, is a more recent and global phenomenon. Only a month after the Held victory, the European Court of Human Rights held a hearing for six Portuguese youth seeking to hold 32 national governments accountable for insufficient climate action. Although Duarte Agostinho and Others v. Portugal and 32 Other States has yet to be decided, its progression is a resounding sign of the growing will of international legal systems to contemplate and prosecute climate inaction. In this context and following COP28, where nations made a historic agreement to pursue an equitable transition away from fossil fuels, the current moment represents a prime opportunity for the young Peruvians to revive their case.

While the Held and Duarte Agostino developments may not directly affect the Álvarez case, said Maria Antonia Tigre, director of Global Climate Change Litigation at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, the broader momentum and pressure they have created is significant. “There are waves in the climate movement and that helps cases that have nothing to do with [each other] in terms of the jurisdictions but that also focus on the same types of legal issues,” she said.

Just last year, Colombia and Chile petitioned the Inter-American Court of Human Rights for an advisory opinion on states obligations’ regarding “Climate Emergency and Human Rights,” while the International Court of Justice is developing an advisory opinion on states’ climate obligations globally following advocacy from the small island state of Vanuatu. Both of these opinions could shape what climate action states are held accountable for, said Tigre. She also highlighted the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child’s historic affirmation of children’s right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment last August as meaningful.

The Álvarez case could frame Peru as a regional climate laggard. Since Ecuador enshrined the rights of nature in its Constitution in 2008, several other Latin American countries have recognized nature as bearing legal rights. Several legal battles for such recognition are ongoing in Peru, including the Álvarez plaintiff’s demand for legal subjecthood for the Amazon.

In 2018, the Escazú Agreement between Latin American and Caribbean nations affirmed the universal and intergenerational right to a healthy environment. Youth in Held successfully argued that this right, also embedded in the Montana State Constitution, includes a stable climate and protection from climate breakdown. Yet, as recently as September 2022, the Climate Action Tracker rated Peru as overall “insufficient” based on its espoused climate action commitments, highlighting its failure to combat deforestation and its approval of oil extraction in the Amazon.

“I see Peru as really far away from climate action,” said Andrea Dominguez, professor of the Environmental Law Clinic at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru and Coordinator of the Alliance of Environmental Legal Clinics of Latin America and the Caribbean, who perceives a lack of climate consciousness within Peru’s government and legal system. Through an amicus brief, she and her students at the clinic aim to “show the judge that this case is part of a bigger movement about climate change mitigation and the connection with human rights.”

Pursuing Legal Climate Action in the Global South

Unlike the youth plaintiffs in Held and Duarte Angostino, the Álvarez youth seek climate action in an emerging upper-middle-income country that has contributed little to climate change but is highly vulnerable to its consequences. This reality complicates their case.

Where countries have contributed more to climate change, the argument for greater climate action seems straightforward. Consider that the United States is the world’s biggest historical carbon polluter and European countries have contributed significantly to global emissions, even as many such countries now seek to model climate leadership with legislation and regulation to further a renewable energy transition. By contrast, Peru’s cumulative historical and present annual contributions to global carbon dioxide emissions are a negligible 0.11 percent and 0.16 percent respectively.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Addressing climate change in Peru, as Climate Action Tracker’s analysis reflects, entails more than avoiding fossil fuel use. Crucially, it requires conserving natural resources that mitigate or, if disturbed, exacerbate the climate crisis. Peru contains 13 percent of the Amazon, one of the world’s most indispensable carbon sinks (although parts are rapidly morphing into carbon sources amid vast forest fires fueled by reckless industrial activity, warming temperatures, and increased drought from climate change). Simultaneously, the nation has major mining, agriculture, and logging industries, which all contribute to deforestation. According to Global Forest Watch and in large part due to these industries, in 2022 alone, Peru lost 236,000 hectares of natural forest—close to the size of metropolitan Lima and the equivalent of 155 metric tons of CO2 emissions.

As Tigre explained, it’s clear that Global North countries have greater responsibilities to reduce their emissions, according to the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities. Nonetheless, Global South countries must take their fair share of climate action. “Especially for these countries that share the Amazon, considering [its] importance for the world and the fight against climate change, there is this obligation,” said Tigre. In a promising move toward realizing this obligation last August, countries in the Amazon Cooperation Treaty, including Peru, put forward a new declaration around joint efforts aimed at Amazon conservation, including in light of climate change. Simultaneously, Tigre acknowledged important calls for Global North finance for Global South climate adaptation and mitigation. The momentum behind such calls inspired a historic agreement around establishing a loss and damage fund to help developing nations confront climate change devastation at COP27. Yet the fund is still being developed and is no panacea. While Peru must rely on its limited coffers, Dominguez said that a lack of sufficient public funds is a persistent obstacle to climate action by the Peruvian state.

Meanwhile, the complexity of calling to conserve an economically as well as environmentally significant natural resource is not lost on Delgado Pérez and his peers, who know that many farmers depend on the Amazon as a source of livelihood. Agricultural practices make a massive contribution to the Peruvian Amazon’s deforestation. Yet Amazon conservation remains essential, he said, not only because the Amazon plays an essential role in regulating climate change but also because it is home to immense biodiversity and countless Indigenous communities, for whom justice is also on the line.

For these reasons, the Peruvian youth want to see major policy change in Peru for Amazon conservation and climate action—similar in scale and nature to that won by young people in their neighboring country. In the landmark 2018 decision in Future Generations v. Ministry of Environment and Others, the Supreme Court of Columbia ruled in favor of young people who had sued the country’s Ministry for the Environment, agreeing that government inaction on climate change and deforestation violated the youth’s rights. The remedy provided to the youth plaintiffs included their participation in developing a plan for Amazon conservation.

“They feel like legal objects, not subjects,” said Ruiz Molleda of the Peruvian plaintiffs, referencing the personal stakes of the case for them. He emphasized the value of Álvarez for making their voices, typically excluded from political or legal decision-making spaces, heard about an issue that disproportionately affects them.

Looking Ahead in 2024

As global temperatures surge, Peruvians and advocates of climate action worldwide are watching to see if Álvarez can compel Peru’s legal system to rise to the occasion of the climate emergency.

For Ruiz Molleda, the decisive factor is politics: The case is “not legally difficult, but [it’s] politically complicated.” He believes the youth will win a ruling in their favor, which could include a full or partial remedy in response to their demands, and importantly outline a legal obligation for the state to take concrete action. Yet the realization of such action is another question. Already, Peru is grappling with new environmental legal rollbacks, most recently the weakening of a law critical to protecting forest areas. Tigre similarly invoked the ongoing lack of implementation of the momentous ruling in the Colombia youths’ case as an example of how a win for the youth in court might still fall short of their demands in practice.

Either way, Delgado Pérez sees the moment as a crucial opportunity for those not already involved to join the climate movement. In addition to urging his fellow youth to speak up for their future well-being, he issued a challenge to older generations: “How do you feel knowing that nothing is being done about a situation that will harm your children, your grandchildren?”

Whether by taking action directly or indirectly on a smaller scale, such as by helping share information about the Álvarez case or living more sustainably, he said, “all of us from our different positions can contribute to making a significant change.”

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

What Your Cheap Clothes Cost the Planet What Your Cheap Clothes Cost the Planet

A global supply chain built for speed is leaving behind waste, toxins, and a trail of environmental wreckage.

The UK’s Climate National Emergency Briefing Should Be a Wake-Up Call to Everyone The UK’s Climate National Emergency Briefing Should Be a Wake-Up Call to Everyone

The briefing was a rare coordinated effort to make sure the media reflects the science: Humanity’s planetary house is on fire, but we have the tools to put that fire out.

AI Will Only Intensify Climate Change. The Tech Moguls Don’t Care. AI Will Only Intensify Climate Change. The Tech Moguls Don’t Care.

The AI phenomenon may functionally print money for tech billionaires, at least for the time being, but it comes with a gargantuan environmental cost.

Backsliding in Belém Backsliding in Belém

Petrostates at COP30 quash fossil fuel and deforestation phaseouts.

Wake Up and Smell the Oil. Your Nation’s Military Is Hiding Its Pollution From You. Wake Up and Smell the Oil. Your Nation’s Military Is Hiding Its Pollution From You.

A fact all but ignored at COP30.

Trump Promised to Bring Back Coal. This Town Listened. Trump Promised to Bring Back Coal. This Town Listened.

Through executive orders, Congress, and a loyalist cabinet, the Trump administration has delivered big for enclaves of coal country like Colstrip, Montana. But how long can it las...