Redistricting for the next decade is nearly complete, with a whole new set of gerrymandered legislative maps. State and federal courts, governors, and some modicum of legislative self-restraint have prevented gerrymandering for the sort of extreme Republican advantage we saw a decade ago, with a map poised to produce a balanced Congress. Yet I can hardly call this result fair. While appellate courts can sometimes lend their blessing to the right result supported by the wrong reasoning, we should not accept a broken and antidemocratic process just because it yields a false sense of balance.

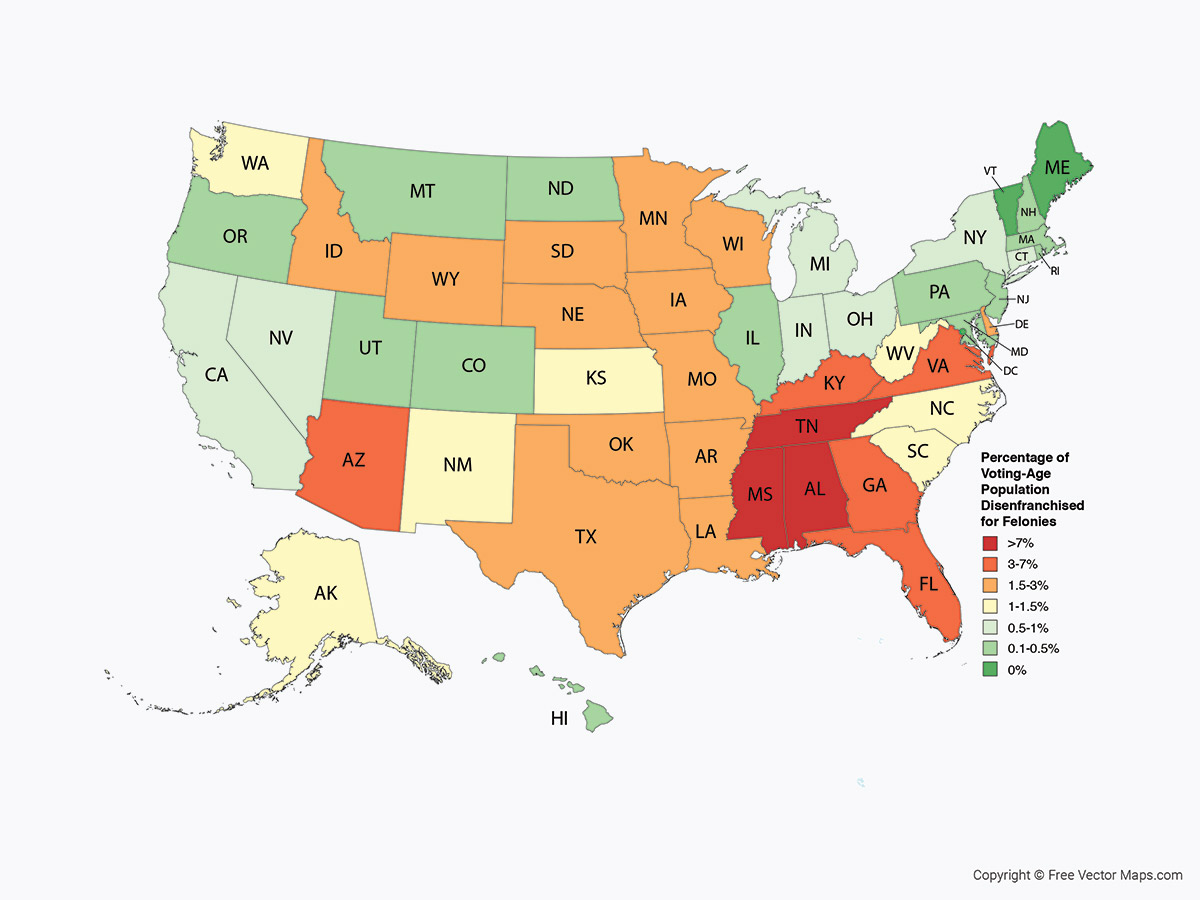

The new congressional maps do little to address the white supremacy baked into the US electoral system. We deny 8 percent of adults the vote because of their immigration status or a prior felony conviction. The data demonstrates that there are at least 42.6 House seats’ worth of disenfranchised adults, by my estimation—and that’s discounting, for the moment, the places where no one has congressional representation. While the bulk are due to immigration status, 9.3 seats’ worth of these exclusions are due to felon disenfranchisement alone. These burdens fall disproportionately on Black and brown communities because of the institutional racism of both our immigration and criminal legal systems.

Antidemocracy in America thrives on suppressing the votes and voices of Black, brown, and poor people, and felon disenfranchisement and unjust immigration standards are two of its most potent tools. States gain seats in apportionment and localities gain disproportionate power in redistricting from the bodies of their residents who cannot vote. Of course, these illicit gains do not fall evenly among the states—only 1.7 percent of adults in Maine are denied the vote, but 16.4 percent are in Florida. Only extremely white Maine and Vermont—the two states that never disenfranchise people convicted of a felony—do not disenfranchise Black voters at a higher rate than their white counterparts.

Even getting this poor approximation of fairness in our congressional maps has required the heroic efforts of a horde of lawyers on behalf of marginalized communities. So far in this redistricting cycle, plaintiffs from communities who should not have to spend their limited resources to vindicate their fundamental democratic rights have filed dozens of lawsuits to fight discriminatory gerrymandering in state and federal courts. These suits consume the efforts of advocacy groups like the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Education Fund, Common Cause, and the ACLU, as well as departments in huge law firms like Dechert, Hogan Lovells, and Cooley, the boutique firm Elias Law Group, and dozens of small and regional firms around the country. Even when litigants make some small progress toward equal representation, the Supreme Court might just shift the goalposts.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Black people shouldn’t have to fight this hard for the right to vote—again. Yet we must, because lawmakers, legislatures, and judges persist in their attempts to preserve white supremacy by minimizing the chance that Black votes will ever matter.

The maps further make a mockery of “fairness” by excluding anyone who doesn’t live in a state, like the 689,545 people in the District of Columbia, the 3.2 million residents of Puerto Rico, or the 338,021 people living in other US territories. Sure, the Constitution included compromises by white men to balance the rights of states—including the allocation of US senators and representatives—but we settled the question of whether the rights of states or people were more important at Shiloh, Antietam, and Gettysburg. A century and a half later, though, the Confederates and their sympathizers still hold sway in the realm of voting rights. We should divorce our notion of who is entitled to vote from the contingent detail of where they happen to reside—by enfranchising Americans whether they live in a state or not and stripping states of the power to disenfranchise voters. We should ensure that every American’s right to vote is honored, without barriers based on criminal convictions, immigration status, or location.

I previously argued at The Nation that we should count the votes of Black people twice. Although that’s still a remedy for centuries of disenfranchisement, it won’t solve gerrymandering. Even sending election staff to the homes of every Black, brown, and poor person to collect their votes won’t be enough—though we should do that, too.

Thankfully, other modern democracies have demonstrated that there are various ways to assign seats in a legislature besides single-member districts. Several forms of proportional representation are used to elect legislatures, such as open party list voting, mixed-member proportional voting, and single transferrable vote. While the technical details of these systems vary, they all group voters into large, multi-seat districts to elect a legislature roughly in proportion to the desires of the entire electorate. Similar options exist to create a national popular vote for president—something most other presidential democracies handle with two rounds of national voting.

The Senate, though, is irredeemable. While the House of Representatives suffers from a few rotten boroughs, the Senate is almost entirely composed of such overrepresented districts by design. There is simply no way to reform an institution founded on the idea that land should be a bigger factor in political power than people. An upper house is a luxury we simply don’t need. We should abolish the Senate.

Rather than forcing marginalized people to fight for their basic rights as citizens in every redistricting and election cycle, we should enact structural changes to protect their rights. If Democrats can’t do this while controlling both houses of Congress and the presidency, we should elect better representatives. We need universal suffrage, proportional representation, a deliberate attempt to collect the votes of marginalized communities, and an end to the Senate as an institution. Even that wouldn’t guarantee fairness, but it’s the bare minimum we must do to make fair representation attainable.