With Abortion Winning on the Ballot, Will Republicans Double Down on a Failing Strategy?

The GOP is increasingly ditching labels like “pro-life” and calling for abortion “limits” rather than bans. But some activists and state officials in Missouri continue to bet on their extreme rhetoric.

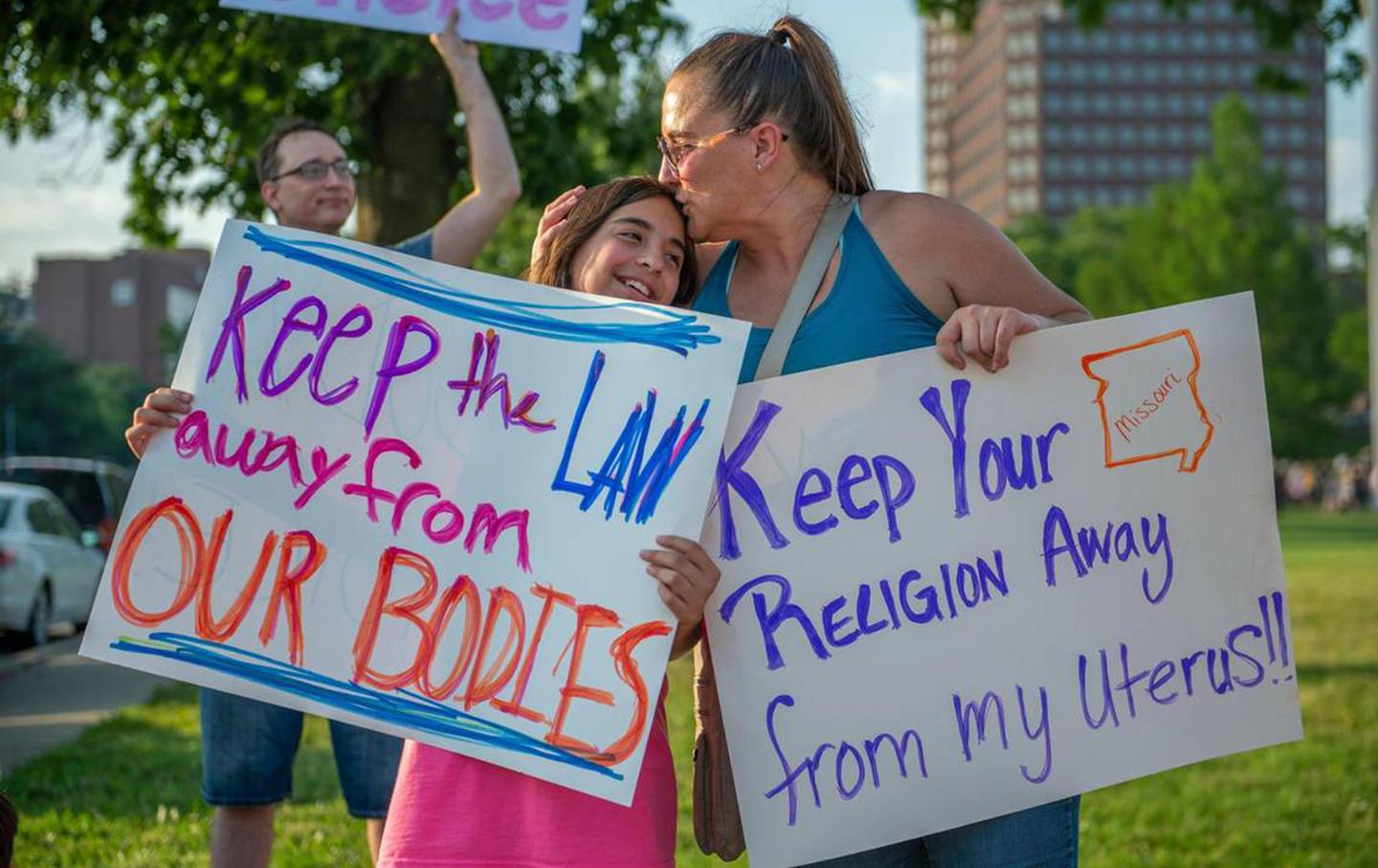

A daughter and mother at a Missouri protest opposing the Supreme Court’s ruling overturning federal protections for abortion rights in June 2022.

(Emily Curiel / Getty)In light of the national outcry against the overturning of Roe, the Dobbs decision has forced a reevaluation of how Republicans speak about abortion, with many of the candidates vying to overtake Trump looking to more moderate stances. After recent polling—and the success of ballot initiatives on abortion in Republican localities such as Kansas and Kentucky and most recently in Ohio—many Republicans now favor doing away with labels like “pro-life” altogether, and speak of abortion restrictions in terms of ‘limits’ rather than “bans.”

Despite this national shift, some state officials still seem to be betting on extreme anti-abortion rhetoric as a winning strategy, including in Missouri. A proposed ballot initiative in the state is currently mired in lawsuits, with anti-abortion state officials framing the issue as a loss of future citizens and tax revenue. “People in Missouri for so long have tried to see how far they can take it, who can be the most conservative when it comes to this issue,” said Tori Schaefer, deputy director of Policy and Campaigns at the ACLU of Missouri.

The proposed initiative, which would appear on the 2024 ballot, would reverse the state’s near-total ban on abortions and restore abortion access by enshrining abortion rights and reproductive healthcare in the state’s constitution. Almost a dozen versions of the proposed constitutional amendment were filed by St. Louis doctor Anna Fitz-James, who is backed by the political action committee Missourians for Constitutional Freedom.

To move an initiative forward, the state auditor must determine a cost estimate, which is then certified by Attorney General Andrew Bailey. But Bailey—believing that State Auditor Scott Fitzpatrick’s estimate of “at least $51,000 annually in reduced tax revenues” was far too low and that “aborting unborn Missourians will have a deleterious impact on the future tax base”—refused to certify the fiscal note. Bailey did not respond to requests for comment.

In April 2023, the ACLU of Missouri filed a lawsuit arguing that Bailey was delaying the progress of the ballot initiative and preventing signature collection. The Cole County Circuit Court sided with Fitzpatrick’s estimate and ordered Bailey to approve the fiscal note, a decision that was affirmed by Missouri’s Supreme Court in July. “Even though I would prefer to be able to say these initiative petitions will cost the state billions of dollars, I have a responsibility to the people of Missouri to not allow my personal beliefs to prevent the auditor’s office from providing a fair cost estimate based on facts,” Fitzpatrick told The Nation.

But Missouri House Representative Hannah Kelly, state Senator Mary Elizabeth Coleman, and anti-abortion activist Kathy Forck later sued Fitzpatrick over the fiscal note language again, arguing that the summary is “insufficient and unfair” and that Fitzpatrick failed to account for potential loss to federal Medicaid funding and state tax revenue due to the abortion of future Missouri citizens. “Missouri voters deserve an accurate fiscal note attached to the ballot initiatives, which will cost the state huge amounts of money, including possibly billions of dollars in health care funding,” said Kelly, Coleman and Forck later in a joint statement to The Nation, outlining their intention to appeal the decision.

Another lawsuit concerned the ballot summary written by Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft—which is the language voters will see if the initiative makes it onto the ballot—calling abortion “dangerous, unregulated, and unrestricted,” suggesting that the measure would allow the termination of a pregnancy “from conception to live birth” and allow for “partial-birth abortion.” The Cole County Circuit Court deemed a number of Ashcroft’s phrases to be argumentative or inaccurate, and Judge Jon Beetem suggested revised summary statements based on the six versions proposed by the ACLU. Ashcroft initially responded to requests for comment, but was unavailable at the time of the interview.

With the issue of abortion language reverberating around the country—in GOP debates and ballot initiatives in several states—a number of Missouri Republicans, too, are taking more moderate stances on the issue. In his bid for reelection, Republican Senator Josh Hawley recently said that “voters ought to be able to weigh in and in every state and jurisdiction they want to,” and Senator Eric Schmitt said that “it’s inevitable that the [abortion] question will be presented to Missouri voters at some point.” While both politicians formerly expressed support for Missouri’s near-total abortion ban, they’ve begun to change their tune with the 2024 elections looming.

“I think there’s this effort right now to shift the rhetoric around abortion,” said Erin Cassese, a political science professor at the University of Delaware currently working on a book about voter attitudes toward abortion. “I think the actual rhetoric people are using is in flux, and that some of these alternative arguments are being tested to see what is going to appeal to people, especially given the polling about opposition to Dobbs. The [existing] moral framework is not appealing to people, so what is going to win hearts and minds?”

But the most anti-abortion Missouri state legislators have doubled down, opening an entirely new line of argument: claiming that abortion access would result in a loss of sales and property tax revenue for the state resulting from “lost citizens.” At other points in the lawsuit, they refer to these hypothetical impacts as the “destruction of thousands of pre-born Missouri citizens a year” and the “lost labor force contributions of aborted citizens.”

The language represents a notable modification of existing abortion messaging appealing to the personhood or humanity of a fetus: it appeals to the idea of the fetus as future citizen and taxpayer, and concerns itself with population decline and “historically low fertility rates.”

Samuel Lee, director of Campaign Life Missouri, cited a 2022 report from the Joint Economic Committee Republicans, claiming that “the economic cost of abortion due the loss of unborn lives is 425 times larger than the earnings loss mothers would be expected to incur when having a child.” Among a number of other objections regarding the potential costs of the amendment, Lee cites a loss of state revenue “because of a decrease in the workforce due to the number of children who are aborted before birth.”

“There’s a lot of assumptions in the idea that the loss of future citizens is a loss of tax dollars for the state,” said Cassese. “The idea that everyone who is born in a state is going to be a taxpayer in that state is an assumption that is not really addressed.”

Concerns over population decline are not without precedent. Cassese points to these arguments’ strong basis in the late-19th- and early-20th-century Comstock Act, a federal law that made it a crime to distribute birth control, or information about reproductive care, by mail. In the same historical period, high birth rates among immigrant groups and declining birth rates among upper-middle-class white Protestants led to fears about the decline of the white Protestant population, and thus attempts to restrict access to birth control and abortion. “Around the time of the Comstock Act in the late 1800s, the justification for restricting abortions was this sort of ‘race suicide’ argument, this idea that different patterns of reproduction is going to lead to a different demographic composition of the country,” Cassese said.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →“I think that kind of feeds into some of the things we’re hearing about demographic threat right now, like Great Replacement Theory—how white Americans are going to be a minority of the population within 25 or 30 years,” said Cassese. The Great Replacement Theory is a far-right conspiracy theory alleging that minority populations will soon overtake the white population, notably espoused by Tucker Carlson and Elon Musk. “Some of [this lawsuit’s rhetoric] is, I think, a veiled racialized argument,” said Cassese, “and some of that is about the decline of the health of the economy, about ensuring the continuation of the race.”

It is yet to be seen whether similar arguments about population decline and fetuses as future taxpayers will remain fringe arguments. Historically, Missouri has been a “testing ground” for national anti-abortion legislation and rhetoric, as Executive Director of Abortion Action Missouri (formerly Pro-Choice Missouri) Mallory Schwarz calls it. For example, a 2022 proposal in Missouri suggested a novel anti-abortion regulation that—though it ultimately failed to be incorporated into any legislation—would have banned Missouri citizens from seeking abortions out-of-state.

In the meantime, more mainstream language arguments remain squarely in the debate nationwide and in Missouri, such as concerns about late-term and “partial-birth” abortions, which were widely decried at the first GOP debate. A majority of Americans support abortion rights, though many would support some restrictions.

But polls of Republican voters offer insight into why more extreme language on abortion may prevail within the GOP: Republicans competing against other Republicans, particularly in local elections in states like Missouri, may appeal to more extreme anti-abortion stances to win their primaries.

However, legal experts have also argued the opposite: that support for abortion access may be a more powerful influence on Republican rhetoric surrounding abortion in 2024 than support for restricting it, even in a state like Missouri. “People who want to lead their party will try to meet somewhere in the middle and not go as far right as other folks,” said Schaefer, pointing to Hawley and Schmitt’s backtracking on their abortion positions. “The cross-state ban was before Dobbs. Last year, the same person who pushed that bill did not push that bill after Dobbs. Even people who push bills like that have been silent. I think the majority of folks who want to be taken seriously in politics will see where the country is headed.”

More from The Nation

A Trump Administration Official Says It Won’t Investigate the Killing of Renee Good A Trump Administration Official Says It Won’t Investigate the Killing of Renee Good

Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche makes clear that the Department of Justice won’t look into the death of Renee Good—but that won’t stop Minnesota from investigating.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s Dream: Love Against Racism Martin Luther King Jr.’s Dream: Love Against Racism

As Dr. King reminded us, “Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.” His words continue to call us toward justice, compassion, and the power of love to confront racism.

It’s Official: The People, Not the Politicians, Are Leading It’s Official: The People, Not the Politicians, Are Leading

In this week’s Elie V. US, our justice correspondent explores the fecklessness of the Democratic Party, MAGA racism, and fighting despite unwinnable odds.

The Week of Colonial Fever Dreams From a Sundowning Fascist The Week of Colonial Fever Dreams From a Sundowning Fascist

The news was a firehose of stories of authoritarian behavior. We can’t let ourselves drown.

Self-Appointed King of Venezuela Self-Appointed King of Venezuela

The United States attacks Venezuela and captures President Maduro. Trump claims that the US will “run” the country for oil interests.