Arab voters could swing the election in places like Michigan—and, if the 44th annual ArabCon convention was any indication, Harris has a huge mountain to climb.

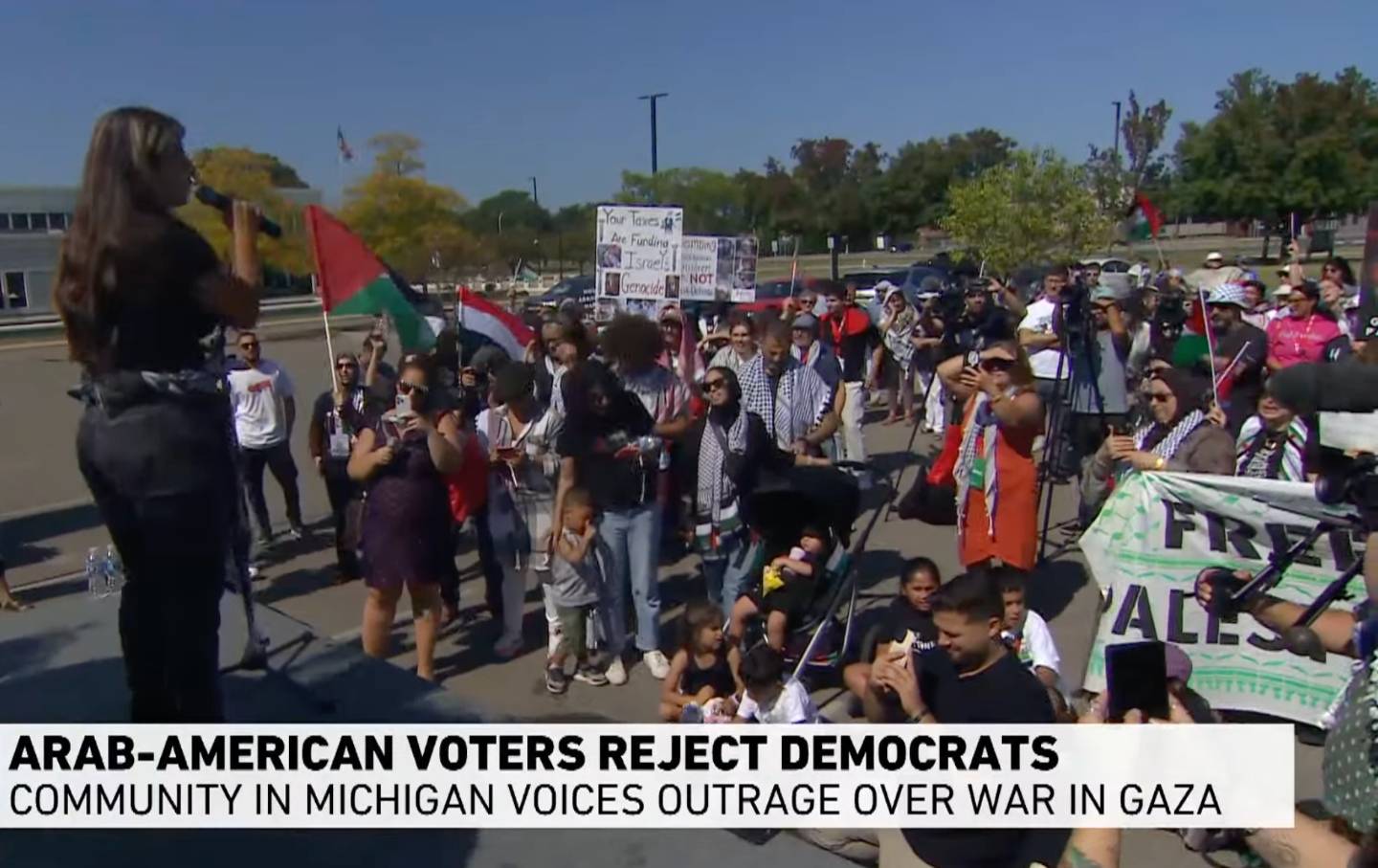

A pro-Palestine demonstration at ArabCon. (Al Jazeera)

There aren’t many places where Jill Stein can expect a rock star’s welcome. But on a September evening in Dearborn, Michigan, when Stein, the perennial Green Party presidential nominee and equally perennial thorn in Democrats’ side, delivered her stump speech in the cream-tiled atrium of the Arab American National Museum, the crowd’s enthusiasm belied her standing in the polls. Although she dutifully rattled off her platform—Medicare for All, a Green New Deal, an end to mass incarceration—there was little doubt why Stein, keffiyeh-clad and silver-haired, was in this particular room at this particular moment: to talk about Gaza.

“There is no lesser evil, in this race, among the two major parties,” Stein said, as the audience roared its approval. “What we have are two greater evil choices: one conducting genocide now, the other urging that the job be finished.” When Stein wrapped up, leading the crowd in a chant of “Free, free Palestine,” attendees swarmed her for selfies and interviews, ignoring the beleaguered organizers’ pleas to clear the room.

If any single event captures the herculean task Kamala Harris faces in persuading many Arab American voters to back her candidacy, it might be the one Stein was speaking at: ArabCon 2024.

The annual national convention of the American Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, a 44-year-old civil rights organization, ArabCon is always political. But this year—devoted, by design and circumstance, to the spiraling war in the Middle East and the upcoming presidential election—provided an especially apt snapshot of the current moment. In a direct challenge to the Democratic Party, its theme was “No Voice Unheard, No Vote Unearned.” The prevailing sentiment, though, was best summed up by one panelist, the law professor Khaled Beydoun, who declared, referring to The Lancet’s recent estimate of the true death toll in Gaza, “I’m not a single-issue voter. I’m a 186,000-issue voter.”

Even the location was significant. In past years, ArabCon has been held in the DC area, but Dearborn, just outside Detroit, is the country’s largest Arab-majority city, and it’s right in the heart of a crucial swing state. Come November, Arab American voters could well determine who sits in the White House. If ArabCon is any indication, Democrats are in trouble.

The 2024 election will be decided by a sliver of ballots in a handful of states. In 2016, Donald Trump won Michigan by a little more than 10,000 votes; in 2020, thanks in no small part to Detroit and its diverse, sprawling suburbs, Joe Biden took the state by about 154,000 votes. Michigan also happens to have the country’s second-largest Arab American population, at about 220,000—a critical constituency in a must-win battleground. Traditionally, Arab Americans are a reliable bloc for Democrats; Biden won 59 percent of the community’s vote in 2020.

But Trump’s odious racism and Islamophobia may have lulled Democrats into complacency. “The main thing is not to have your vote taken for granted,” one ArabCon speaker, the veteran Palestinian journalist Said Arafat, said onstage at the Ford Performing Arts Center. He described a conversation he’d had with a Democratic operative: “Basically, he said, ‘The Arab and Muslim vote is going to come to us. Are they going to vote for the guy who imposed the Muslim ban? Are they going to vote for the guy who gave Jerusalem to Israel, who gave the Golan to Israel?’ and so on. They take you for granted.”

The numbers suggest that doing so would be a mistake. Thanks to the Biden administration’s backing of the Israeli bombardment in Gaza and Lebanon, Arab American voters are abandoning the Democratic Party en masse. When the ADC surveyed its membership, only 27.5 percent said they would vote for Harris—a massive improvement over Biden’s 7 percent in a previous poll, but miles behind Stein, who boasted 45 percent support. One in four respondents said they wouldn’t vote at all.

Other organizations have raised similar red flags: A recent Arab American Institute poll found Harris and Trump virtually tied among Arab American voters nationwide, while a survey of Muslim voters by the Council on American Islamic Relations put Harris and Stein in a dead heat nationally, with Stein beating Harris in Michigan, Arizona, and Wisconsin. (For context, Stein polls at about 1 percent among the general public.) The Harris campaign has noticed; for the first time ever, Democrats are running attack ads against Stein in key swing states, including Michigan.

Of course, as many speakers at ArabCon took pains to point out, Arab American voters are not necessarily Muslim, and vice versa; nor are these communities monolithic. But the overall trends are clear—and they spell bad news for Democrats. “I think Harris has made the calculation that, ‘I am entirely going to overlook the pro-Palestinian segment, and make my bet that I can win without them,’” Beydoun told me after his panel. “That, to me, is very telling.”

Harris’s defenders say that she has struck a more empathetic tone on Gaza, and that, unlike Biden, she’s capable of talking about Palestinians as if they’re actual people. But since she has ruled out an arms embargo on Israel—a key demand of pro-Palestinian activists—there are limits to what a change in rhetoric alone can accomplish.

“The overwhelming feeling is that [Arab voters] feel better about Vice President Harris, but they still don’t believe she’s earned their vote,” Chris Habiby, the ADC’s national government affairs and advocacy director, said in an interview on the sidelines of ArabCon. “When they think about the race for president, they still feel that, if you are complicit in or actively supporting genocide, that is a red line.” Habiby himself is Palestinian American; his father is from Haifa, his mother from Gaza. He told me he lost three extended family members, including a 6-month-old baby, last October, when Israel bombed the Church of Saint Porphyrius, killing 18 people at the ancient Christian site, which was sheltering hundreds of displaced Palestinians. Since the rest of his relatives were able to escape to Egypt, Habiby considers himself lucky. “But it also means that I no longer have family in Gaza,” he added. “In a future, free Gaza, maybe my family goes back and resettles, maybe they don’t. But that connection to the land isn’t there anymore.”

One ArabCon panel, billed as the convention’s “Election Strategy Session,” did reach something of a consensus: However you feel about the top of the ticket, the speakers agreed, downballot races still matter. “When you sit at home because you’re mad at whoever’s running for president, guess what?” Linda Sarsour, the prominent Palestinian-American activist, said. “You are forfeiting the very things that actually impact your daily life.”

A later panel, featuring four Arab American Democratic state legislators, was meant to underline the importance of the rest of the ticket. The speakers discussed what they were doing to push for an arms embargo, how they were supporting college students who’d been criminally charged for participating in encampments, and their work with the Uncommitted movement, which, during the Democratic primary, had tried to send a message on Gaza by voting against then-candidate Biden. (Thirty Uncommitted delegates ultimately wound up at the Democratic National Convention, representing 650,000 voters from eight states.)

By any metric, the four panelists represented triumphs of Arab American political representation. But almost from the moment the politicians took the stage, the crowd was restive. Even the moderator, a consultant named Hebah Kassem, posed the sort of pointed questions one might expect of an antagonistic journalist rather than a friendly interviewer. “You’re all a part of the Democratic Party, and I believe some of you have actually endorsed Harris,” she said at one point. “How have your efforts to push our cause for justice in Palestine rendered material change, and not just rhetoric?” Then, when the audience got involved in the conversation, the air in the room became even more charged.

One attendee accused Georgia state Representative Ruwa Romman of “continuing to defend a genocider”—that is, Harris. Another, her voice shaking with emotion, called Harris a “genocide enabler” and asked each panelist to state unequivocally whether they planned to vote for the vice president. A third also directly addressed Romman. “How do you plan to maintain trust and credibility within the Palestinian, Muslim, and Arab communities,” she asked, “when there is a perception that your support for Harris is at odds with advocating for an end to the genocide in Gaza?” During the DNC, when representatives of the Uncommitted movement agitated for a Palestinian-American speaker, Romman was one of the names they put forward; although they promised to endorse Harris in exchange, and even offered for the DNC to vet and edit the speech, they were still denied.

Romman said that she was not the only person who had been proposed as a speaker, and that Uncommitted was trying to “expose the fact that no matter what we could have done…the systemic racism is so ingrained, particularly on a national level, that it was still not going to be enough.” She also pointed out that she had not, in fact, endorsed Harris. “If they want my endorsement, which includes my vote, she has to call for enforcing international humanitarian law,” Romman said. “It’s that simple.” But, by this point, she was facing angry heckles from the audience.

Another speaker, the Colorado state Representative Iman Jodeh, noted that the vice president had proven ideologically malleable on a number of issues, which might make her flexible on Israel and Palestine as well. But, while Jodeh, like Romman, stressed that she hadn’t endorsed Harris, she too struggled to compete with interruptions from the crowd. Even the ambivalent moderator begged for calm. “OK, guys,” Kassem said. “Can we let them finish, please?”

The mood was rather different at that night’s gala, in the banquet hall of a nearby cultural center. While attendees waited for their salad and hummus and lamb kabsa, writer Fady Joudah read a poem dedicated to Palestine (“To those who guard their dead from the starving dogs of war / who are different from the dogs of war that starve them”) and the ADC feted a series of awardees: Doctors Against Genocide, the Amity Foundation, Students for Justice in Palestine. The most seemingly incongruous honoree of the evening was Macklemore, who arrived in sunglasses, surrounded by a modest entourage, to receive the ADC’s Rachel Corrie Award, named for the 23-year-old American crushed by an Israeli bulldozer while protesting home demolitions in Gaza in 2003. Few people, upon hearing Macklemore’s breakout 2013 hit “Thrift Shop”—an excruciating work of white-rap doggerel—would have predicted he’d become one of pop culture’s most outspoken supporters of Palestine, even releasing the student-encampment anthem “Hind’s Hall” earlier this year. But, then again, a great deal has changed over the past decade.

At the gala, I struck up a conversation with Tariq Habash, who participated in one of the weekend’s most moving panels, featuring officials who quit the Biden administration in protest over the war. Habash worked in the theoretically unrelated Department of Education until the contradictions felt too great to bear; in January, he became the first Palestinian American, and the first Biden political appointee, to publicly resign. He, too, emphasized that Democrats were taking Arab American voters for granted.

“I think we’ve heard from a lot of community members who are hurting, who are visibly upset about the campaign not internalizing the feedback they are repeatedly getting,” Habash said. “I hope that the Democratic Party recognizes how important that vote is, not just here in Michigan, but in a lot of the battleground states, in a lot of states where the races are very well within the margin of error, and there are substantial Arab and Muslim populations.” For his part, Habash, a self-described loyal Democrat, told me he still hadn’t decided what to do in November. (He has since launched a new Middle East–focused political action committee alongside Josh Paul, a former State Department official who also left the Biden administration over Gaza.)

Finally, it was time for the evening’s main event. Amid voter discontent over Israel and Palestine, third parties have sensed an opening. Jill Stein has made Gaza the centerpiece of her campaign, and even the Libertarian presidential nominee, Chase Oliver, calls the war a genocide and demands an end to US military aid to Israel. But there is no independent candidate with a longer pro-Palestinian track record than Cornel West, the theologian and public intellectual, who was ArabCon 2024’s keynote speaker. That night, at the banquet hall, West took the stage wearing his trademark outfit: thick glasses, black tie wound around his white collar, cuffs shooting from his sleeves. The rapturous welcome he received was rivaled only by the rapturous welcome that, a few days earlier, greeted his ostensible rival, Stein, who, as it happened, was sitting in the audience.

If Stein’s chances at the presidency are less than zero, West’s are, if possible, even lower; he lacks the institutional backing of any party at all, and has described his own campaign as “jazz all the way down.” But, over the course of his half-hour oration, he reminded the crowd that, whatever his shortcomings as a politician, the man sure can preach.

“What kind of human being do you choose to be, in the short move from your mama’s womb to tomb?” West asked. “You’re not here that long. That’s what is at stake in 2024, with God. Far beyond the election. Far beyond politics. The question is whether enough of us will shatter the indifference. The great Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel used to say, ‘Indifference to evil is more insidious than evil itself.’ How do you shatter indifference? How do you shatter callousness?”

When West finished, he was, like Stein, rewarded with euphoric applause and mobbed by supporters. Neither candidate stands a chance on November 5. But they were here, by invitation, at ArabCon 2024—and Kamala Harris was not.

Drew NellesDrew Nelles is a freelance journalist, podcast producer, and fiction writer.