Bernie Sanders has not chosen the easy road in American politics. During the Cold War, in the early 1960s, he decided to join the Young People’s Socialist League. In the 1970s and ‘80s, he pursued third-party and independent politics in Vermont. In the 1990s and ’00s, he was among the few progressive voices in a rightward-moving Congress.

All along the way, however, from his years in the Burlington mayor’s office to his stint as an outsider in the House of Representatives to his sometimes lonely work in the most elite of all American bodies, the US Senate, Sanders remained committed to what he calls a “political revolution”—a mobilization of working-class people from the bottom-up to create egalitarian change.

Rather than accepting the narrow parameters of existing US politics, Sanders has always believed that ordinary people can change those very parameters. His legendary persistence paid off during the 2016 and 2020 presidential campaigns, when he showed that his vision of economic and social justice had a mass base in the United States.

Bhaskar Sunkara, president of The Nation, met with the Vermont senator at his office in Washington, DC, on Wednesday, July 10, to discuss his political past, the lessons from his two campaigns, and his advice for a new generation of organizers.

Bhaskar Sunkara: In late 2014, you stopped by the Nation office when you were thinking about running for president. Take me back to that moment: As a lifelong independent, were you hesitant about running in a Democratic primary? And more broadly, what were you goals and expectations for the campaign?

Bernie Sanders: Look, the Democratic Party is a corporate-dominated party, which was increasingly moving to the right, and had turned its back on the working class of this country. That’s no secret.

When I was elected mayor of Burlington way back in 1981, we actually defeated a five-term incumbent Democrat. The coalition we put together then is the prototype of everything I’ve done since. We had the support of people who lived in low-income housing projects; we had the support of environmentalists; we had the support of the Burlington Vermont Patrolmen’s Association, the cops who were unhappy with the scheduling and the negotiations that they had had with the incumbent administration.

Back then, and now, my belief is that the way you win elections is by speaking to the needs of ordinary people. That’s what I did back then, that’s what we did in 2016. It is really not all that complicated.

Sunkara: In that first presidential race, you were portrayed as a fringe candidate, someone who didn’t have a chance…

Sanders: In 2016, Hillary [Clinton] was the anointed candidate. She’s a woman, she’s experienced, the wife of a former president. What more do you need? What’s there to discuss?

Sunkara: I was part of the DSA’s [Democratic Socialists of America] Draft Bernie campaign in 2014, and my hope was for you to beat Martin O’Malley.

But despite being unknown to many people at the start of the campaign, your message resonated with even self-identified moderate voters, independent voters in rural areas.

Sanders: Underlining everything is [that] I have never ceased to believe that virtually every single issue we talk about has the support of a strong majority of the American people. So people talk about “fringe” when you say that really healthcare is a human right, it’s fringe tackling climate change, it’s fringe raising the minimum wage to a living wage, building affordable housing.

The discussion, and the Democratic Party, had moved so far to the right that, when we talked about these items, we were labeled that way.

Sunkara: You laid out a model with your campaigns in Vermont, and in 2016 that had a lot of success—clear rhetoric and a set of popular demands that you’ve been consistent on for years. But do you think that blueprint is actually being followed by progressives today?

It seems to me that even when other progressive politicians are articulating similar demands as you, something isn’t clicking as far as the focus and appeal beyond deep blue districts.

Sanders: Two answers. First of all, let’s take a deep breath and appreciate the enormous success of the progressive movement in electing the dozens of strong progressives in the House of Representative. In 1991, in the House, I started the Progressive Caucus. We had five members…. It is an enormous step of seeing young people, energetic people, smart people, people of color, often women, elected. [These are] extraordinary success stories and the progressive movement should be very proud of that.

So, if the question that you’re really asking me is, has there been enough focus on class as opposed to other issues? I would say, probably not. But people like Pramila [Jayapal] and Alexandria [Ocasio-Cortez] and Ilhan [Omar] have done an extraordinary job in standing up for their constituents and working families all over the country.

Sunkara: There’s the question of our rhetoric on the left. But there’s also the way in which identity has been wielded as a cudgel by centrists against those of us who do push universal, class demands that challenge corporate power. Do you think that happened to you, particularly during the 2016 campaign?

Sanders: Absolutely. Look, deciding what you prioritize is the most important thing in politics. What if I asked you what are the most important issues? What would you do if you were dictator of the world, what would you do tomorrow? And to me, I look at the world today and I come from a working-class family, and I see 60 percent of the people living paycheck to paycheck. I see people living under enormous stress. I see working-class people dying 10 years younger than wealthier people. I see 60,000 people dying because they can’t afford to get to a doctor when they should.

I also see police officers beating up young black kids. I see women being discriminated against, gay people being discriminated [against], all of that is real. I think from both a political point of view and a moral point of view, it is absolutely imperative that we focus on the lives of ordinary people, black, white, Latino, gay, straight, and what’s happening to them.

It’s also important for us to see what’s happening not only in America, but all over the world, to all of these center-right parties, center-left parties, people are saying, “You’ve forgotten about us. We live in a rural community, we’re making no money. We can’t afford healthcare. Anyone paying any attention to us?” And they are giving up on democracy.

So, to answer your question, what is most important to my mind on a long list of priorities is that we create a nation in the wealthiest country on Earth that guarantees a decent standard of living to all people.

I live 50 miles away from the Canadian border. They spend half as much per capita on healthcare and somehow they make sure that all of their people have good-quality healthcare. Is this a utopian vision? I don’t think so. You go to Finland and other countries, they somehow manage to make sure that their kids are able to get good quality education from pre-K to graduate school without worrying about the cost.

Those are the things that I think we’ve got to focus on. I think it’s right from a moral perspective, from a policy perspective, but also from a political perspective.

Sunkara: Along those lines, so much is made today about the culture war in the country and divides between so-called red and blue states, rural and urban areas, like you alluded to. What can the left do to bridge rather than feed into these divides?

Sanders: Let me give you a personal story on that. At some point in the 1980s, I don’t remember when, we had a constitutional amendment on the ballot in Vermont guaranteeing women’s rights. I was on that ballot, as well.

I strongly supported that amendment, but Vermont had many conservative towns where people were voting Republican, and guess what? They voted for me, and they voted against that constitutional amendment.

Point being, progressives are going to have to take a deep breath and understand that not everybody in America may agree with them on certain issues. Take a deep breath and understand that what is most imperative is that we bring the working class of this country together around the agenda that speaks for all people.

Sunkara: How do we make the issues we want to foreground more salient in campaigns. Does it happen naturally because they’re the things most connected to people’s daily lives? Does it happen because we just keep mentioning healthcare, jobs, trade, etc. in our messaging?

Sanders: You’ve got to put this question into a broader context, which nobody talks about. We’re living in a moment where the oligarchy is growing extremely rapidly, and part of the crisis is that the most important issues are not being discussed. Above and beyond healthcare or education or decent-paying jobs is the issue of power—especially since Citizens United, and we’ve seen this recently with the Biden thing [the effort to replace Biden as Democratic nominee] too. The donors, the donor class is telling us what we should do. The amount of money coming in from the billionaire class to control the political process is clearly obscene. The concentration of ownership is unacceptable. The level of income and wealth inequality in America is unprecedented.

So, the bottom line of everything else is, who controls the society? Who is benefiting from the society? And right now, the people on top are doing extraordinarily well with the status quo. They want to maintain the status quo.

Sunkara: Do you think Biden’s economic policies were a decisive break from the neoliberal policies of past Democratic administrations, like Bill Clinton’s?

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Sanders: Well, let’s just go back a few years. First of all, Biden, who historically has been a moderate Democrat, was smart enough to recognize the political power of the progressive movement. And that’s why during his campaign we put together a series of task forces dealing with all the major issues facing the country. And that in itself was a break. That was a recognition that there were many, many millions of people in this country who were not happy with the status quo. They wanted to move this country in a fundamentally different way.

We sat down [with Biden and others] and we worked out agreements on a whole host of subjects. He came into office in the midst of the horrific Covid pandemic, and I think what has not been discussed enough—and most of that is because of Democratic cowardice—is the significance of the American Rescue Plan and what that means, this $1.9 trillion program. I was involved in it because I was chairman of the Senate Budget Committee at the time, and it was the most consequential piece of legislation for the working class since the 1930s.

There was virtually no money in that for the wealthy or corporate America. This was a program that focused on the needs of workers. In one bill, we cut childhood poverty in half—we got $1,400 to every working-class person and kid in this country—we dealt with the childcare crisis. What that showed to me is the potential of government to be transformative. That’s one piece of legislation, and I will tell you that Biden was there every step of the way.

“Get more, Bernie. We’re with you. I’ll sign it. You get it, we’ll sign it.” That’s what he said, OK? And that piece of legislation, most importantly, symbolically showed what government could actually do. And by the way, if you check your polling, Joe Biden was at his highest point of favorability at that moment, I think in March, April of ’21.

I have my strong disagreements with Biden over Gaza and healthcare and God knows what else. But he had the guts to say, “All right, we are going to move from an emergency piece of legislation, the rescue plan, to take on the structural deficiencies in this country.” No one did that since the 1930s. After that he said, “You get me the bill, I’ll sign it”—I don’t want to make him look bad here, but he said, “Don’t worry about the money. I’ll sign it. You do it; we’ll sign it.”

We came within two fucking votes in the Senate to do that—[Senators] Manchin and Sinema, corporate Democrats were the barriers—and, of course, it was whittled down in the House, as well. But we were talking about a transformative piece of legislation in terms of housing, in terms of childcare, in terms of healthcare, in terms of education. No other president since FDR would’ve pushed that legislation.

Sunkara: What do you make of the argument that some of this legislation was an important injection of cash to provide relief for working-class people, but that it essentially subsidized demand for necessities like childcare, throwing money at problems that require more planning and state capacity to properly solve?

Sanders: I agree that, in so many respects, the system is broken. And I don’t think most Americans would disagree with me when I say that the childcare system, for example, is broken.

A child psychologist would argue that from zero through 4 are the most important years of a human being’s intellectual emotional development. So a rational society would say, “My goodness, if those are the most important years to create healthy people, we’re going to make an enormous investment. We’re going to have the best people we can. You want to be a childcare worker? Wow. You’re going to need all kinds of training and we’re going to pay you really well, because you’re doing really important work.”

We’re nowhere near that, but at least we were able to respond to the current insanity where if you have two kids you might be paying $40,000 or $50,000 a year in childcare. How are you supposed to do that?

We’re dealing with not the broad fundamental issues, but the day-to-day issues of the working-class people who can’t afford childcare, [and that the] people who are working in childcare are making McDonald’s wages. So that’s what we did in ARPA [American Rescue Plan], and what we tried to do in Build Back Better.

But more change is needed. It’s not revolutionary, but the healthcare system is obviously broken. Look around here, how many people are even talking about something like Medicare for All? How many?

Sunkara: It was actually going to be my next question. Medicare for All was a core part of your presidential campaigns and it seemed to be very much in the zeitgeist with even people like then-Senator [Kamala] Harris signing on. Is it a disappointment that it seems to be out of the discussion completely. Is that just the result of congressional math?

Sanders: No, it is the campaigns. My campaigns were unique. Why was that? Because as much as the media and the establishment would prefer to ignore what we did, when you go out and you have rallies of 10, 15, 20, 25,000 people, when you’re leading the polls all over the country, you can’t quite ignore the program that we were running on.

We ran on a very strong set of issues, had a strong agenda. So suddenly I’m talking about Medicare for All in front of 20,000 people, and people are saying, “Yeah, that’s what we need to do. Well, oh, yeah, I support Medicare for All. It’s a good idea. Yeah, it’s popular. It’s popular.”

But if somebody is not out talking to 20,000 people, you’re not on the front pages every day talking about that issue, it loses its leverage, and then you’re back to the establishment talking about the need to improve Medicaid or to do this or to do that.

The media and the establishment do not like [Medicare for All]. So unless you create the dynamic and the excitement where millions of people are saying, “This system is broken, we need something else,” that immediately falls back and you’re back to the establishment mentality.

Sunkara: You’ve laid out how important you thought some of the proposed legislation was and even what was actually passed, like the infrastructure bill. But despite the scale, it still seems like so many working-class Americans still don’t associate the Democratic Party as the party of working people.

In the 1930s, New Deal legislation and FDR’s rhetoric flipped a switch. There was massive realignment. Workers that were previously Republican voters flipped over to the Democratic Party. It was so obvious that the president’s program was in their interest.

Is that a failure of communication? Is that because of the scale of the transformation isn’t there yet?

Sanders: The problem is not the messenger and it’s not the message, it’s the reality. If your job went to China and you saw a 50 percent reduction in your wages, if your kid can’t afford to go to college, if you can’t afford to go to the doctor, if you can’t afford childcare, if your way of life is despised by the elite, if they don’t [value work where you] get your hands dirty, that you have a more traditional views of marriage and so forth and so on, why would you vote Democratic?

It personally distresses me coming from a working-class family to see so many white working-class people move to the Republican Party, in some cases right-wing extremism, and what I have said for years is this is not the success of the Republican Party, it’s the failure of the Democratic Party. I think as you just indicated, there was a point, 1948, when Harry Truman was president, [you could] go out on the street, and say to somebody, “Which party is the party of the working class?” Everybody would say Democratic, no matter what your views may be, right? Which party is the party of big money, big business, the banks? Republican Party.

Go out on the street today, you ask that questions, you’re not going to get that answer. So Democrats made a decision, since the early ’70s maybe, to say, “Look, we want corporate support, we want corporate money and we will follow their lead,” and that’ll lead you to NAFTA, lead you to PNTR [permanent normal trade relations] with China. It leads you to not raising the minimum wage here in 20 years. It leads you to legislation like the Affordable Care Act that does some good, but that was originally, I believe, a Republican proposal.

There has been a major transformation, and I think Trump is moving aggressively right now to accelerate that transformation to make the Republican Party the party of the working class, and I don’t see much feedback. You tell me what’s happened in the Senate in the last year or two to suggest to an average worker that they’re wrong [about the Democratic Party]?

So what I’m trying to do is urge the president to be very strong in analyzing why we are where we are—and that is everything to do with the power of corporate America, the power of the billionaire class—and bring forth a set of ideas prepared to take them on to improve lives of working people. I think that’s the only way that the Democratic Party can regain the working class of this country.

Whether they’re prepared to do that, remains to be seen. I hope the president understands that.

Sunkara: Some of this shift is among not just white workers but Hispanic workers and others. There’s a sense that Democrats are part of a cultural elite and out-of-touch with working-class Americans.

I think sometimes the problem isn’t the actual identity issues but how they’re framed. The vast majority of Americans aren’t for violent policing, they’re not for people getting sexually harassed at work or discriminated against. But on all these issues there does seem to be an embrace of a certain activist rhetoric that comes more out of academia than out of working-class environments.

You see this in both progressive milieus but even among more centrist Democratic Party figures. I can’t help but feel like the messaging would be very different if the party had the deeper class roots it once had.

Sanders: Sometimes the politicians don’t come from those [elite milieus], but they are surrounded by people who do. If people are walking in day after day saying, “I represent Pfizer and I represent Novo, so let me tell you my problems. Oh, and by the way, I look forward to attending your fundraiser next week.” If you’re surrounded by lobbyists who tell you why tax breaks for billionaires make a lot of sense or why we can’t raise the wages for workers because it’ll be terrible for business, if that is who you are surrounded with and you’re not out talking to ordinary people, that’s the kind of mentality that you develop.

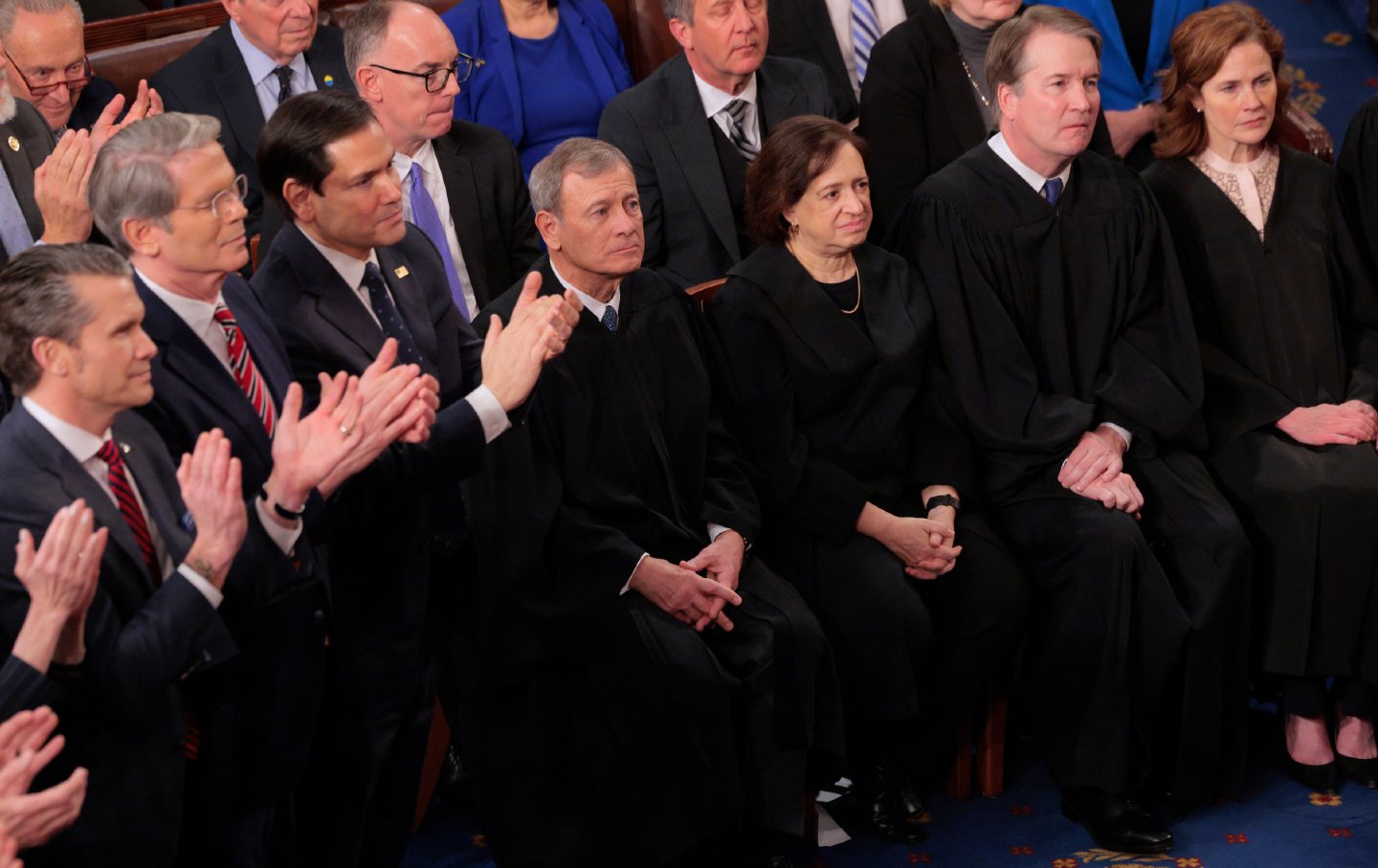

The level of class consciousness, if I may use that term, in the Senate, is quite low. I mean, you’ll hear some passion [from Democrats] talking about some racist event that takes place, you’ll have uproar, or some sexist event or homophobic event. That 60,000 people die because they can’t afford healthcare, not much of an issue.

Sunkara: Or the class consciousness is high just in the other direction.

Sanders: Yes, exactly.

Sunkara: You’ve invoked FDR and the legacy and New Deal Democrats throughout your career. Is it fair to say that you believe that the Democratic Party could once again be transformed into a party of working-class people.

Sanders: Thinking back about the campaigns that I ran—we would schedule our events often to coincide with major Democratic Party events in the states. So, you go to Colorado when the Democratic Party is having their big state event. So, we would have a rally in the morning and then the afternoon we’d go to the Democratic event, and the reality between these two events was like day and night. We’d have young people, we’d have energy, then you go to Democratic land and it’s much, much smaller and older, and it was like those are the two visions of future of the Democratic Party.

Does the establishment want to open their doors to people who want fundamental change? No, they don’t. They have a nice situation now, they want to keep it.

Sunkara: Let’s talk about some of your political history. You were active in the civil rights and labor movements in the 1960s…

Sanders: Compared to other people, I was not active. I was at the University of Chicago, I was a member of what was then called the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), I was one of the leaders in the sit-in at the University of Chicago demanding an end to segregated housing. That’s about it. I was not a big-deal leader, but I got arrested.

Sunkara: Of particular interest to me is that you also joined YPSL [Young People’s Socialist League] at the time. How were you shaped by the organizers you met around then? I always felt like this formation mattered to the rhetoric you gravitated for, which is in some ways—and I mean this as a compliment—more Old Left than New Left.

Sanders: My years at the University of Chicago were very formative to me. I grew up in a school that was about 98 percent white. My family was not political. We didn’t have any books in the house. It was a Jewish neighborhood, voted Democrat.

At the University of Chicago, I was not a particularly good student. I spent a lot of time in the basement of the Harper Library there. I would go down to the stacks and I’d read a lot about history and stuff. And also, to your point, I joined Young People’s Socialist League, the YPSL, and people were giving me an analysis and an understanding that I had not had before, a material understanding of why did things happen rather than, “Oh, this is not good. That’s not good.”

Also, while I was there, I got a summer job with a union that no longer exists called the [United] Packinghouse Workers of America that had their own militant history. They were a very impressive union who brought together blacks and whites and people from all over the world who were coming to do these terrible jobs in the stockyards, and I worked there for a summer a little bit. And also the civil rights movement was not just at the university. I got involved with some neighborhood groups, because adjoining the University of Chicago was a predominately black neighborhood called Woodlawn, and so I began to interact with people there, interact with people at the SPU, the Student Peace Union. So what I learned there was the interconnectedness of things and the nature of class society in a way that I had not previously understood.

Sunkara: You leave for Vermont, I guess, by the middle of the 1960s.

Sanders: I originally bought some land with my then-wife in ’64.

Sunkara: From that vantage point, did you have any perspective on what became of the New Left and its trajectory and the broader counterculture?

Sanders: As far as the New Left, I was strongly against the war in Vietnam and participated in demonstrations. I was not terribly active, I must say. [As for the counterculture.] even then I was not impressed by… what did Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman call themselves?

Sunkara: The Yippies.

Sanders: Yeah, I felt they were ignoring the working class of this country and being into more cultural issues. Obviously, women’s rights was important, sexual freedom was important, but class I think was deemphasized more than it should have been by some of these people.

Sunkara: Do you feel like your national campaigns or even your earlier electoral efforts would’ve been easier if you didn’t have a self-identity or a background as a democratic socialist, and instead you were able to just label yourself from the 1960s through the present as just a New Deal Democrat?

Sanders: The answer is no, and I’ll tell you why. When you call yourself a democratic socialist, you’re part of a tradition. I’m aligning myself with history. I’m aligning myself with a vision. I’m talking about international solidarity. And the other thing is when you talk about democratic socialism, then suddenly you’re not saying, “Oh my God, I’m so smart, I have all the answers for the problem. Do this and don’t do anything else. That’s a good idea.” What you’re saying is the system is broken. The system is broken, you need a new system, and you’re identifying what that is.

People see that it’s not nibbling around the edges, it’s not just healthcare, it’s not just education. [It’s about] should a few people in this country and the world have so much wealth and so much power? That’s a systemic question. And you call yourself a democratic socialist, you are addressing those issues in a way that they have to be addressed.

Sunkara: You’re from New York, but you moved to Vermont. I know you were an old Brooklyn Dodgers fan, but can I get you on the record to declare your continued allegiance to New York professional sports?

Sanders: Politically, I’ve said this before, taking the Dodgers out of Brooklyn was devastating, not only to me but to the entire borough. I had no idea as a kid that the Brooklyn Dodgers could ever be taken away. And it taught me a little bit about capitalism that somebody, against the wishes of everybody in that borough, could simply move to Los Angeles. So no, it’s stayed in Brooklyn.

[Though] when I was mayor of Burlington, we brought a minor league baseball team into the city. It was wonderful. For five bucks, you’d come in, your kids are there, they watch quality baseball.

Sunkara: Final question: Do you have any advice for a young, idealistic person who wants to make change?

Sanders: I’m not good at giving advice to young people. I would say this: If your first impulse is to run for office, rethink it. I see too many young kids say, “Oh, you’ve inspired me. I want to become president. I want to become governor. I want to become the senator.” Wrong. Find out what your passion is—find out what moves you. Is it the environment? Is it women’s rights? Is it workers’ rights? And get your hands dirty doing that work, and sometimes you can have more of an impact organizing your brothers and sisters on the job in a union than you can have for running for office.

Running for office is good, but it’s not the only way. So, trust your passion, but most importantly, go to the grass roots, get your hands dirty. Do real work with real people.

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation