The Discourse Around Biden’s Health Has Been Odious

We should be able to talk about the president’s condition without sinking into harmful speculation or pernicious stereotypes.

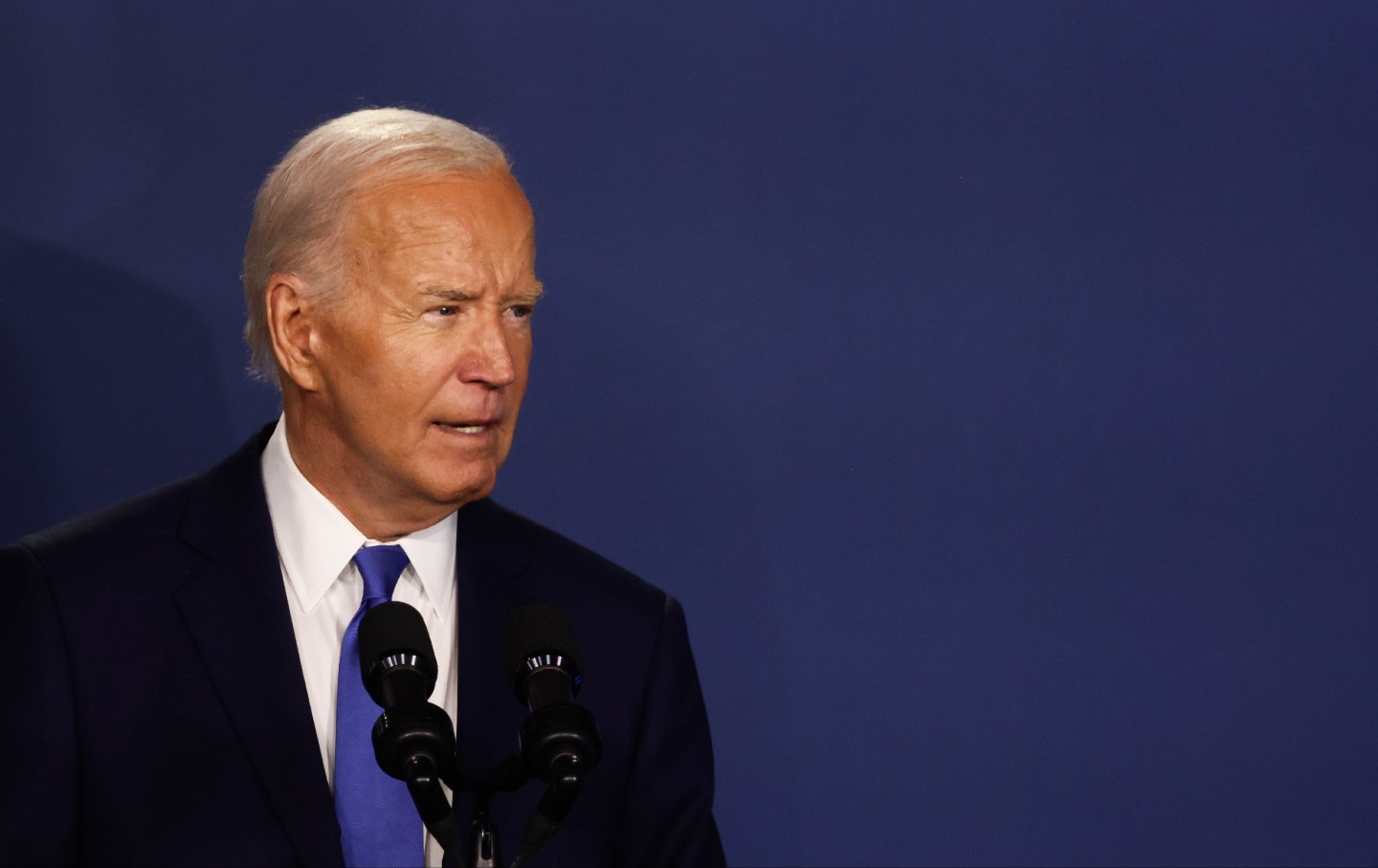

Joe Biden at the Ukraine Compact during the final day of the NATO Summit in Washington, DC.

(Jakub Porzycki / NurPhoto via Getty Images)The authors of the Denver Principles, the 1983 statement widely seen as one of the AIDS movement’s founding documents, refused to reduce what was called by some back then gay-related immunodeficiency syndrome, or the “gay plague,” into a subject of shame and derision. They also refused to allow people living with AIDS to be turned into victims. While these early AIDS activists may or may not have known it, they were following in the footsteps of advocates for people with disabilities who demanded their rights to have agency over their lives rather than be treated as second-class citizens.

Over the past two weeks, we’ve seen why these fights have mattered so much: because the stigmatization of disease and disability is never far from the surface of our national discourse.

It’s been remarkable to see how the focus on President Biden’s age has slid into old stereotypes. No matter what you think of the President’s debate performance, his cognitive state, or his fitness to continue his campaign, it should be possible to discuss these issues respectfully, and without descending into wild speculation. There are serious questions to be asked about how this is all being portrayed, and real concerns about how it has set back our quest for equal rights for people living with disease and disability in the United States.

Two moments have stood out to me: the press-driven frenzy over whether Biden has Parkinson’s disease, and the decision by one of the world’s most august weekly periodicals, The Economist, to put a walker on the cover of its July 6 issue along with the caption “No Way to Run a Country.”

The Parkinson’s disease rumor, which first appeared in The New York Times, stemmed from visits to the White House by a Parkinson’s expert. People started wondering whether these visits might be linked to a presidential diagnosis of the condition. From there, the rumor got wall-to-wall coverage, with neurologists drafted in to diagnose Biden from afar, even though they had no firsthand knowledge of his health. Of course, within a few days, the White House came back with a statement that made these multiple visits far more ordinary—the doctor in question was providing care and neurological consultations to many on the White House grounds and the president was not living with Parkinson’s.

But the damage was done. The rumor of Parkinson’s was to function as a kind of scarlet letter—this time to suggest that the president was no longer fully there, with a potential diagnosis that put him in the bucket of “victims of disease.” It was a reminder of all the old ways that those of us living with lifelong conditions were made to feel subhuman, as people meant to be pitied or derided—not citizens of equal standing in our democracy and certainly not fit for positions of leadership. People living with Parkinson’s are leading full, meaningful lives, and contributing greatly to their communities and the nation. The fact that I have to say this in 2024 shows us how far we have to go until diseases like Parkinson’s (or HIV) don’t get thrown around as put-downs.

One could consider the Parkinson’s disease incident as a sad exception to how disease and disability are being deployed at the moment, but The Economist’s cover was a shocker. A walker? Of course, the editors thought it was a good shorthand for signaling Biden’s infirmity, but it simply made them look out of touch, cruel, and ignorant. As the National Disability Rights Network said:

Abraham Lincoln, perhaps our greatest president, experienced depression. Franklin Roosevelt used a wheelchair. Dwight Eisenhower had dyslexia. John F. Kennedy wore a back brace. In more recent times, Texas Governor Greg Abbott uses a wheelchair. Former New York Governor David Paterson is blind. Supreme Court Justice Sonya Sotomayor has diabetes. Are these people limited in their professions by their disabilities?

The answer is no, but for The Economist, a walker was simply another scarlet letter moment, meant to disdain and deride.

The fact is that people living with chronic disease, with disability, who are simply over 65, number in the millions and they are a vital part of our nation’s fabric. I can hear some saying, why are you getting so worked up over this, it’s just a side issue to the larger topic at hand? Well, how we treat each other is central to our lives and central to our politics. Donald Trump’s grotesque mockery of people living with disabilities was a flash point in the 2016 election and GOP policies are meant to gut programs that support people living with chronic diseases and disability.

And lest we forget, during our response to Covid, both parties dropped the ball on protections that would minimize risk to people living with chronic disease and disability, at the same time creating the conditions that have led to many people suffering from long Covid.

The way the press and the public see people living with disabilities—or those simply growing old—matters if we don’t want to sink back into 19th-century Social Darwinism. It matters if we want to avoid the brutishness of American conservatism. The idea that “diversity is our strength” is not just a slogan. There are millions now living with chronic diseases and disabilities, or living and thriving in old age. Most of us will pass through one or more of these categories during our short time on this planet.

How we talk about Biden matters because his specific issues are used as a stand-in for a wider national conversation about aging, disability, and illness. The more we turn toward analyzing his ability to serve based on pernicious speculation and stereotypes, rather than facts, the worse things will get.

All that many of us can think of at this moment is getting rid of Trump in November. But the bigger question is, what kind of world do we want to build together in his wake? The spectacle of the past two weeks should give us pause. The near-mockery of those living with disease and disability as a wedge for political purposes has been odious. If you don’t think President Biden can do his job, say that as many times and in as many ways as you’d like, but using any possible disease or disability as a casual pejorative is not fair game—it’s just prejudice and ignorance.