Madera County has been a stronghold for the Republican Party in California’s San Joaquin Valley for decades. Billboards this fall lined rural highways, urging the recall of Governor Gavin Newsom, pasted over peeling Trump/Pence posters. If Newsom’s fate had rested on Madera County, he would no longer be governor—60 percent of county voters went against him. Fifty-six percent went for Trump in 2020, slightly more than 2016. In fact, the last Democratic presidential candidate to win the county (barely) was Jimmy Carter in 1976.

But in the city of Madera, the county seat, changing demographics among the county’s 156,000 residents are creating political challenges to the conservative order. Almost 60 percent of county residents now list their origin as Hispanic. African Americans, Native Americans, and Asian Americans make up another 10 percent.

In the city’s District 5, which combines a dilapidated downtown with a large eastside barrio, California’s growing community of Indigenous Mexican migrants has put forward its first candidate: Elsa Mejia, who is running for an open seat on the city council.

Mejia was born in nearby Fresno, to parents who’d come to the Valley from the Oaxacan town of Santa Maria Tindu. A decade ago, the Leadership Council of Santa Maria Tindu, an organization of former residents of the Mexican town now living in the United States, carried out its own community census. They wanted answers because the government does not count Indigenous migrants, even in the Census. The council found that migrants living in Madera from just this one Mixtec hometown already numbered 2,500. Together with migrants from other Oaxacan communities, Mixtec-speaking people now are a sizable part of Madera’s people.

California communities of Indigenous migrants maintain their ties with their Mexican towns of origin. Growing up, Mejia would return with those family members who could cross the border to visit her grandfather in Tindu. He would try to teach her Mixteco. “But we didn’t stay long enough, so I just learned a few words,” she laughs. Later, she lived in Oaxaca for a year, working for Rufino Dominguez, a revered migrant leader in California who went back to Oaxaca to head its Institute for Attention to Migrants. Mejia later worked for a decade as a reporter for The Madera Tribune, and then edited Fresno’s progressive monthly, the Community Alliance. Today, she works in the communications staff of Service Employees Local 521, the Valley’s union for many public workers.

Mejia’s laugh belies the many things her parents, and Mixteco parents like them, did over the years to make sure their children know and enjoy Mixtec culture. They formed organizations to carry that torch, from dance groups to language classes. Every year, the Binational Fronte of Indigenous Organizations (Frente Indigena de Organizationes Binacionales, FIOB) mounts a dazzling festival showcasing the dances of Oaxacan towns, called the Guelaguetza. Its Fresno festival is just one of several. California’s Indigenous Oaxacan population is so large that there are more Guelaguetzas organized here than in Oaxaca. In Madera itself, FIOB has organized a yearly basketball tournament, the Copa de Juarez, on the birthday of Benito Juarez, Mexico’s first Indigenous president. It organized protests against the celebration of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Americas, accusing colonizers of trying to destroy Indigenous culture and people.

Culture is a principal basis of organization in Mixteco communities, a key understanding for winning an election in Madera District 5. Even if she has problems with the language, as many second-generation immigrants often do, Mejia understands its importance in mobilizing her community. “It’s very important for people to have access to public services in their own language,” she explains. “We still don’t have equal access, even in Spanish. You can’t take a driving test in Mixteco. Everybody should have access in the languages they speak.”

FIOB fought over many years for language rights in the Valley. It won interpretation in Mixteco and other Indigenous languages in California courts before that right was recognized in Mexico. But Fidelina Espinoza, FIOB’s state coordinator who staffs its Madera office, says she supports Mejia because language is still a huge problem tied to the lack of city services in general. “When our parents go to school for a conference with teachers, there are no interpreters, and sometimes even no conference,” she charges. “We have no translation to help us access what we need, and the city doesn’t support cultural programs or even community gardens for our young people.”

Downtown Madera could use a lot of community gardens. The main street, Yosemite Avenue, is lined with small businesses, mostly with Spanish-language signs, that are clearly having a hard time. One standout attraction is Sabores de Oaxaca (Oaxacan Flavors) where a stream of Mixteco-speaking customers find a small, cool restaurant. Many come inside still in sweat-stained clothes from a day in the fields, in 115-degree heat.

Nevertheless, other businesses on Yosemite Avenue could clearly use city support. Across the freeway chain stores and malls get a lot more attention. Downtown homes are mostly modest rentals, many in need of help as well.

“The city has abandoned downtown,” Mejia charges. “Those little stores and restaurants were hit hard by Covid, but where was the help? People in District 5 have the lowest incomes in Madera. A lot of people have no homes and there’s no city program to build housing. The subsidies in the federal bills for renters never got here.”

“Things are going to change if Elsa is elected,” promises Antonio Cortes, Central Valley director for the United Farm Workers. Cortes also comes from Tindu, and today works in the union’s Madera office. “Oaxacans are very numerous and important here,” he says. “We’re always struggling with the city for resources, and we deserve representation. She comes from a farmworker family, and has that commitment.”

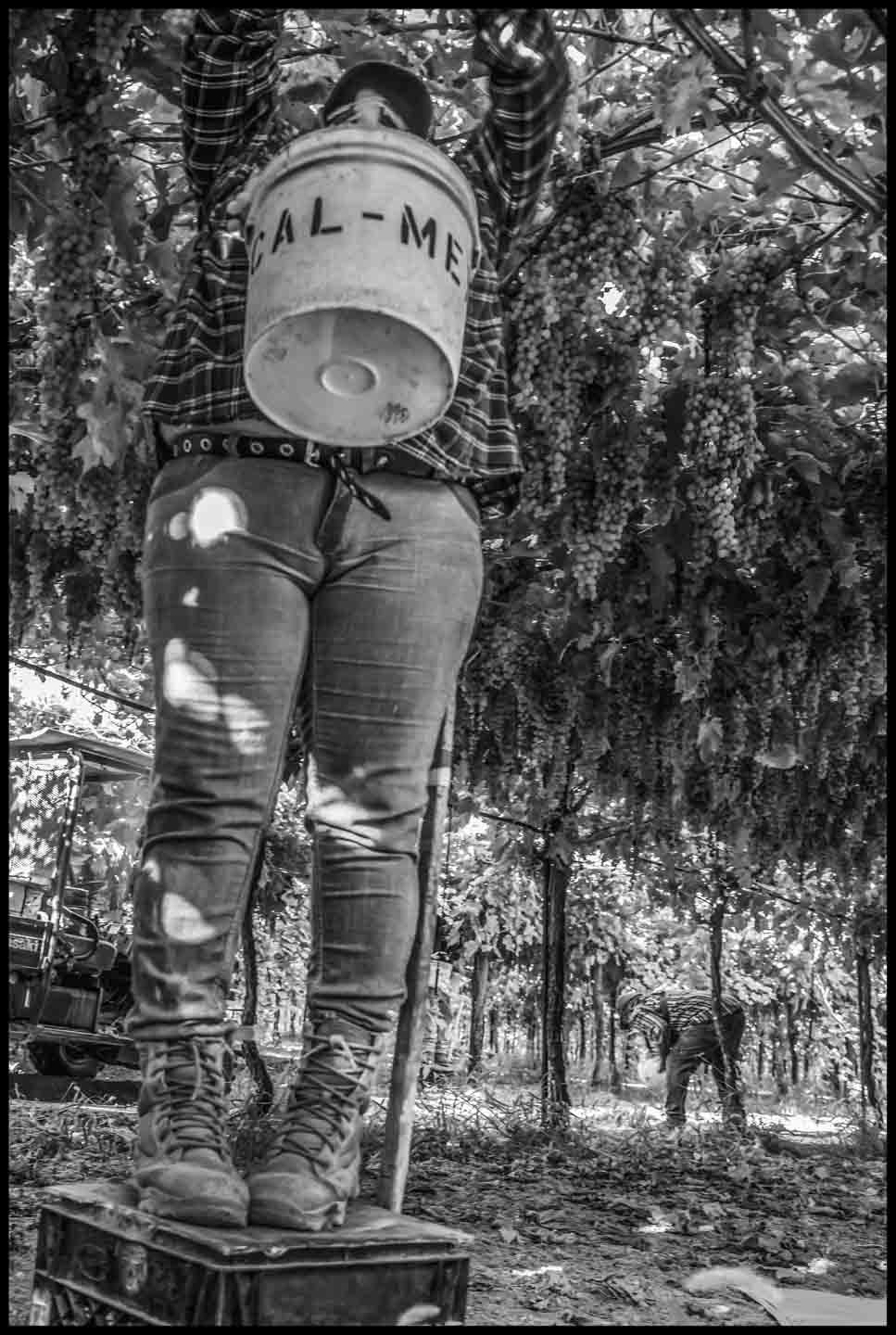

Out of an economically active population of 85,000, about 23,000 Madera County residents work in the fields, according to demographer Rick Mines. His studies show that the median annual income for a farmworker is between $10,000 and $12,499, while for a family the median is between $12,500 and $15,000.

In the pandemic, poverty translates into illness and death. Madera County has had over 22,000 Covid-19 cases (14 percent of the population) and 266 deaths. Only half of its residents are vaccinated. Reporting Area C, which includes downtown and the eastside barrio, has the most cases, almost a third. By comparison, in Silicon Valley’s Santa Clara County, only 7 percent of residents got the virus, and over three quarters are vaccinated. Every day activists in FIOB go out to the fields to sign people up for shots. UFW organizers visit members in the almond orchards, bringing masks, sanitizer and other protective equipment.

Mejia’s chances of winning come from her connection to these campaigns and organizations, working on concrete community problems. She’s running for an open seat, and her opponent is another Latina, Matilda Villafan. But in challenging the economic priorities of the San Joaquin Valley, Mejia doesn’t have an easy path to election. For instance, she believes that “farmworkers who work during the pandemic should be paid better, since they’re risking their lives. And not just them, but their families as well. This should be part of treating them with dignity as workers.” The growers who put up those Trump signs can’t be happy about that.

She thinks there are about 2,000 eligible voters in her district, but there’s no precise number for those who come from Indigenous families. It is a complicated question, for several reasons. In the huge migration of people out of Oaxaca, the first wave of migrants to reach California arrived in the mid-1980s, and they’ve continued to come ever since. Because the last immigration amnesty in 1986 had a cutoff date of January 1, 1982, most of these migrants have been undocumented. For them, citizenship, the ability to register to vote, and the political rights that come with that, are out of reach.

If all the immigrant farmworkers in the San Joaquin Valley could vote, Kevin McCarthy would probably not be the representative from Bakersfield and head of the Republican congressional caucus. Using citizenship to restrict the franchise has successfully prevented the formation of a voting base for more worker-friendly politicians, and more progressive legislation.

Mejia represents the new generation of the children of these families, born here and therefore citizens. Her campaign is part of their entrance onto the political stage in communities where immigrant workers contribute the bulk of the labor, but cannot vote. Over time, that could affect California politics as profoundly as the immigrant upsurge did in Los Angeles in the 1990s.

But it does make it difficult to determine who the Oaxacan or Oaxacan-descended voters are in District 5, and how to mobilize them. In an era of scientific election campaigns, like those already unfolding for 2020’s congressional election, lack of such concrete information is a cardinal sin.

But sometimes what scientific campaigns lack is an organic connection to local communities and their struggles. Mejia is not running against Trump, at least not directly. She’s running on her ability to speak to the concrete needs of her district, which in the end conflict with those of the ranchers, with all their flags and recall signs. On November 2 this year, Elsa Mejia will have the chance to show that kind of strength.