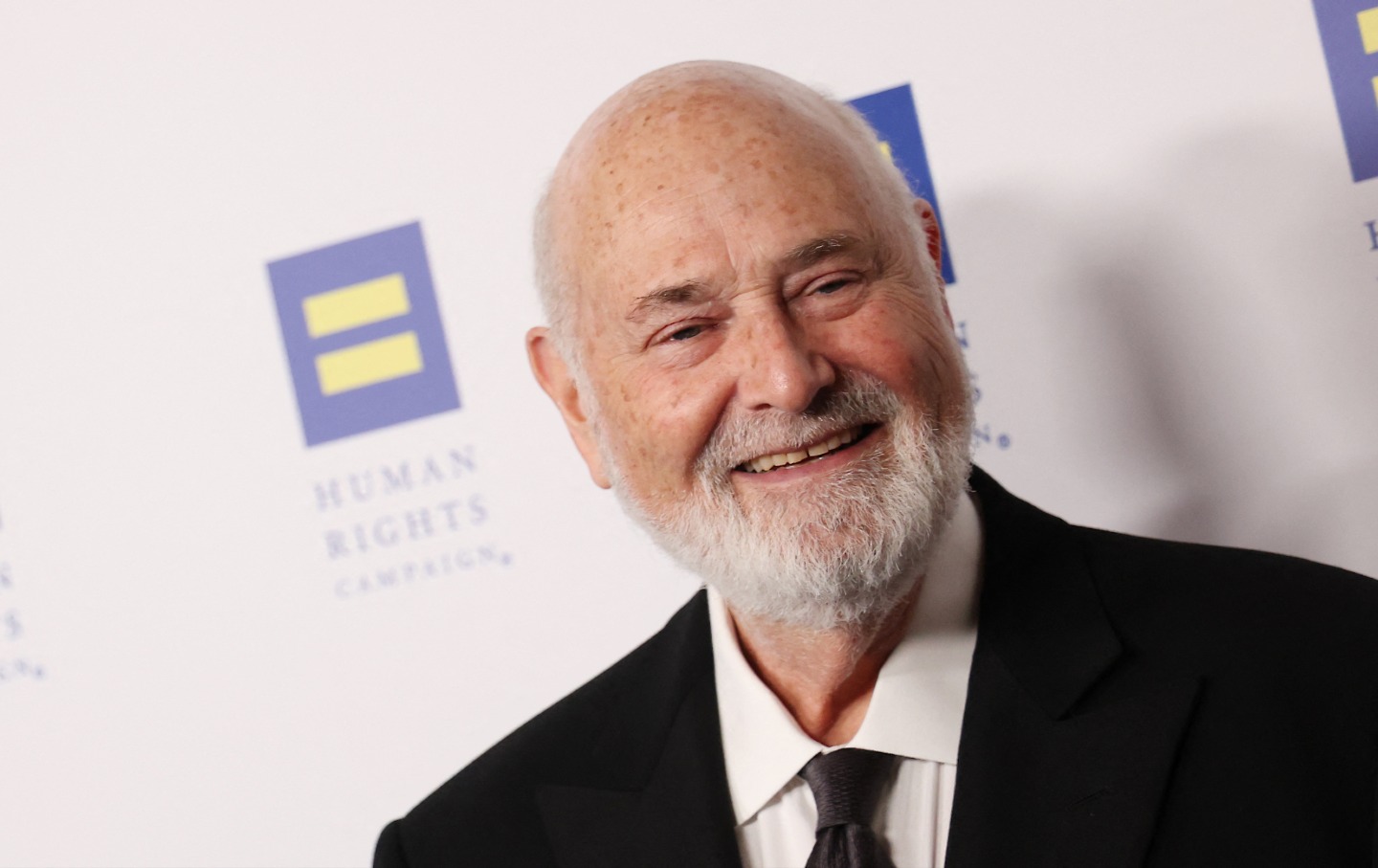

Chris Hayes was The Nation’s Washington editor from 2007 to 2011. He started out writing for the Chicago Reader, then In These Times. He went from The Nation to MSNBC, and became host of All In with Chris Hayes, which won an Emmy. His new book is The Sirens’ Call: How Attention Became the World’s Most Endangered Resource. This interview has been edited and condensed—read the full transcript here.

Jon Wiener: I have a friend who refuses to watch Trump on TV. Why not? “Because,” he says, “Your attention is the most valuable thing you have.” In your new book you describe your own struggle to pay attention to what is most valuable—especially in the morning, when you sit on the couch…

Chris Hayes: “In the morning, I sit on the couch with my precious younger daughter. She’s six years old, and her sweet soft breath is on my cheek as she cuddles up with a book asking me to read to her before we walk to school. Her attention is uncorrupted and pure. There is nothing in this life that is better. And yet I feel the instinct, almost physical, to look at the little attention box sitting in my pocket. I let it pass with a small amount of effort, but it pulses there like Gollum’s ring.”

JW: And what is it that you call “the single most distracting device in history”?

CH: It’s certainly the smartphone. The introduction of the iPhone in 2007 by Steve Jobs is a useful marker of the beginning of this age.

JW: Initially this was called “the age of information” because information now is infinite. But you say there’s a more important element here. What’s that?

CH: It’s a mistake to understand information as the central aspect of this form of economic relations. Yes information is infinite. There’s tons of information. It’s easily replicable. The resource that’s finite in the information age is actually attention.

JW: Information is infinite, attention is limited.

CH: And information is cheap, and attention is expensive. And that’s precisely because attention can only be in one place at one time. If someone takes your attention, they have it, and you no longer do.

JW: What we’re really interested in here is politics—how people competing for power gain the attention of potential supporters. How can we progressives gain the attention of potential supporters, and then how can we hold onto their attention? Please tell us the answer.

CH: Capturing attention is art, not science. And attention exists in two different realms with us. There are the things that at scale will reliably grab attention: the loud and obnoxious, the obscene, the prurient and the lurid. We know those categories. Donald Trump is all of those things. When you’re competing with everyone against everyone else, those are the kinds of things that are going to reliably capture attention.

But at the same time, one of the amazing things about what people will pay attention to is that it’s endlessly varied. There are people that will watch operas, there are people that will binge obscure television shows, there are people that will sit and look at a sculpture for an hour or listen to a symphony for two hours. I will watch carpet cleaning videos online—something I didn’t even know existed until recently.

JW: Wait a minute, carpet cleaning videos?

CH: Oh man, they’re so good. It’s like 15 or 20 minutes of someone taking an incredibly dirty rug and cleaning it.

JW: Okay.

CH: It’s incredibly relaxing and satisfying. So the point is that there are certain formulas for grabbing and holding attention. All of us in journalism know about ledes, and we know about conflict and we know about narrative arcs and characters, all the things that we learned in order to hold attention. But then there’s innovation. People do cool new things. And it turns out that human ingenuity still retains the ability to push out past what we thought were the frontiers of what people will pay attention to.

JW: Of course Trump is the political figure who has most fully exploited the new rules of the attention age. First, he got himself in the gossip columns on Page Six of the New York Post, then he became a TV reality show host, then he became a candidate. But getting all the attention in the world does not seem to make him a happy man. Is that just him? Or is it something about what you call “social attention”?

CH: I think it’s both. I think that he has stumbled upon this insight about the import of attention because of something deeply broken and irreparably sad within him: a voracious desire to be recognized; frankly, to be loved. And one of the sick tricks that social attention plays, particularly on the Internet, is that it gives us a synthetic form of the thing that we most seek as human beings. What we really want as a human being is recognition. That recognition forms the foundation for all of the relationships that are meaningful in our lives: relationships with friends, with lovers, with people we work with—attention is necessary for that, but it’s not sufficient. The experience of attention from strangers, particularly in social settings online, gives us a taste of this recognition, but can never quite fulfill that taste, and creates this kind of compulsive addictive seeking of ever more of it. And you see that with Trump a hundred percent.

JW: Even without Trump, life in the attention age is, you say, “more anxious, more depressed, more isolated; we have fewer friends, we see them less, we struggle to read in depth, the political sphere is more polarized, the information atmosphere is more polluted.” But there must be some way out of here. You say there are ways to restore what you call “our collective control over our own minds.” If our attention is the most valuable thing we have, then we come to a foundational question that is harder to answer than we might think: What do we want to pay attention to? This is something you’ve thought about a lot. You’ve written a book about it, a really compelling and wonderful book. What’s your answer?

CH: There are universal things: I want to pay attention to my wife, to my kids, to my family, my parents, who I’m very lucky to have with us. I want to pay attention to my friends, I want to pay attention to my hobbies and endeavors and projects. I want to pay attention to cultivating my intellectual pursuits like reading and writing books and maybe working on some other things I want to develop. I want to get better at playing guitar.

And I want to pay attention to my job. When I’m working on my work, I feel honored and privileged. I think it’s important work, and I want to do the best possible job with it.

And in all those moments, I don’t want to feel that frittered-away sense, that tug against my will, that weird sense of shame, of regret, a kind of foggy memory of what you just did with the last 20 minutes of your life. I think we all experience this in different ways to different degrees.

JW: You say, “We’re very likely to see the growth of a market for alternative attention products, sort of the way there’s been a market for natural food, for organic farming, for the neighborhood farmer’s market.” Tell us a little more about that.

CH: The food analogy is really interesting here because there’s a parallel process in which the global industrialization of food production and food sales produced a backlash. It started with folks who were dropping out and going back to the land and starting organic farms and starting natural food stores. And all of this was kind of fringe and weird and hippie. But those critiques grew in their force as more and more people came around to feeling the same way about industrial food processes. Our alternative food culture, food ecosystem, and food economy were built out of that initial rebellion. And I think we’re going to have the same with our digital culture.

We used to have a lot more noncommercial spaces online. They’ve all been taken over by commercial spaces: the platforms. But actually the Internet that I first came to love was a largely noncommercial Internet. It was an Internet in which people could connect to each other through open protocols that were facilitated in a cooperative setting. That’s not to say there was no commerce online; there was tons. But the fundamental networks of connection were not owned by anyone.

And the fact that it was built once before means that it genuinely can be built again, in the same way that in physical life we moved between public and private spaces, between commercial spaces and noncommercial spaces all the time. Even in hyper-capitalist American society, we have noncommercial spaces.

And then I think we’re going to start to see much more forcible regulation of attention and the platforms.

JW: What would that look like, regulating the market for our attention?

CH: One place we’re seeing it is with children, with attempts to regulate the age minimums for kids online. That’s a contested policy area. There are people on the left who think it’s a bad idea, particularly because of young teenagers having access to information about forms of human sexuality that are not heteronormative—for folks that are queer and trans. And I totally understand those concerns. I don’t think they’re ridiculous.

But the principle that we shouldn’t be monetizing the attention of minors seems obviously true to me. The question is how we implement that. It’s like, ‘Well, the only way to get information if I am trans or queer and I’m starting to learn about myself is through the platforms,’ which is a perfectly legitimate argument. But that speaks to the poverty of these noncommercial alternatives that we really have to build—in fact, rebuild, because they once existed.

JW: You end your book by saying that, for the attention economy, we need something like the slogan of the campaign for the eight-hour workday. What was that slogan?

CH: It was, “Eight hours of rest, eight hours of work, eight hours for what we will.” And I think that “what we will” is so profound. It’s so beautiful. “What we will.” What do we want to do with our lives in the third of the day that we’re not sleeping and we’re not working?

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation