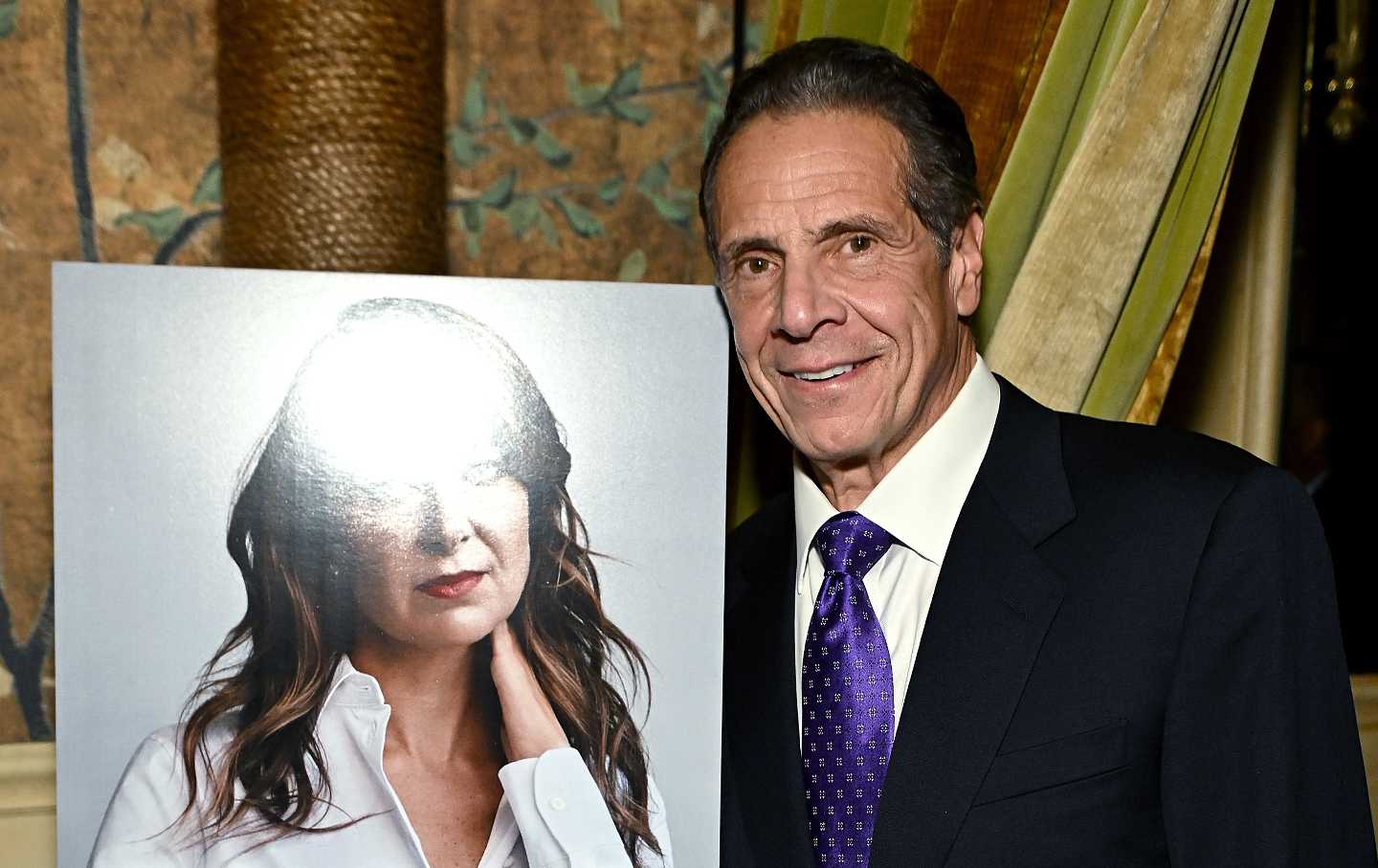

Cuomo’s Top Defender Inadvertently Validates Victims of Sexual Harassment

Melissa DeRosa’s new memoir attacks the women her former employer preyed on. Why can’t she see what she has in common with them?

What’s Left Unsaid—a new memoir by former Governor Andrew Cuomo’s top aide and continued defender Melissa DeRosa—is not a book that anyone should buy. It’s not well-written or particularly insightful and I can’t imagine who, beyond exactly five people in Albany, the publisher thinks will pay money to read it. Like many other vanity projects pitched as setting the record straight, it’s more of a patchwork of journal entries that spin out into such detailed (and deranged) conspiracies that it reveals more about the depths of the author’s personal misery than anything else.

So why am I bothering to write about DeRosa’s “life at the center of power, politics, and crisis”?

Because while attempting to debunk the entire #MeToo case against Cuomo—the book’s evidence-free theory is that a single woman organized the others to lie because haters gonna hate—DeRosa shares her own story of sexual harassment. In doing so, she validates the 11 women who occupy so much of her mindshare. I’m not even sure she realizes it.

About a third of the way into the book, DeRosa recalls a 2020 incident involving the former Albany bureau chief of The New York Times, Jesse McKinley. As she tells it, they were sitting in his backyard at a kind of peace summit after a particularly adversarial press conference during the pandemic. She had two glasses of wine; he had two bottles. That’s when the tenor of the conversation veered away from the professional: He asked her about her eye color, then grabbed her by the wrist and begged her to stay when she attempted to leave. She describes being understandably “unsettled” and immediately called a colleague and even her soon-to-be-ex-husband to recount what happened. She then told a bunch of other co-workers and learned of two other incidents a few years earlier. She also told her friend Nick Confessore, another Times reporter, who revealed to her 10 months later that he’d relayed the incident to the managing editor of the Times, to no avail. Shocked that the company knew and seemingly did nothing—and even allowed McKinley to report on the subsequent #MeToo allegations against Cuomo—DeRosa formally filed a complaint with the Times.

She writes, “There was a clear conflict of interest—one that was known at the highest levels at the Times. I also believed that I wasn’t alone in experiencing his behavior. And I wasn’t going to be ignored any longer.”

Sound familiar? A woman is sexually harassed, there are no witnesses to it, but in her distress she immediately tells other people and soon learns that her experience isn’t an isolated one. She does not file a report, but learns months later that the institution her harasser worked for knew about it. Said woman becomes incensed and finally decides to take action on behalf of herself and others. If we are to believe DeRosa—and I do—why shouldn’t we believe the many women who reported being harassed by Cuomo? Why shouldn’t we take their—and their outcry witnesses’—word for it, when DeRosa offers nothing more herself? Why should we question their timing, as she does repeatedly, when she doesn’t even report what happened to her for nearly a year? And if the Times is guilty of inaction, why shouldn’t we hold DeRosa responsible for her failure to follow state law or the executive chamber’s own administrative procedure for sexual harassment?

It’s clear that the Times’s response was lacking and that DeRosa has every right to be irate. But none of that undoes the verified allegations against Cuomo, thanks to the attorney general’s independent investigation, which pored over hours of testimony and meticulously corroborated every public report that appeared in the Times (and the many other publications DeRosa spares). Nor does it absolve her of her own misdeeds, which she never takes any responsibility for. Far from it. She’s currently suing a young woman named Kaitlin—a former Cuomo aide and relatively minor character in the whole saga—to strip her of her privacy by forcing the courts to reveal her full name for no other reason than to torture her. For more details on the extent of her campaign of legal terror against various 20-something young women, see this incredible profile by Rebecca Traister—whom DeRosa has also, as if on cue, threatened to sue.

DeRosa’s justifiable anger over McKinley does nothing for her book’s main thesis: that Cuomo is the victim of a lying cabal of women who’ve “weaponized” #MeToo just to take him down. She never for a moment entertains the possibility that the thing they have in common—rather than an unexplained motive to make him suffer—is that they were all victims of his predation. This boggles the mind considering that she expects the reader to just take her account about McKinley at face value (which, again, I do). To some extent, her incredulity makes sense. After all, DeRosa weaponized her own experience to try and get back at the Times for their reporting on Cuomo. She wasn’t acting on her own behalf. And that’s what’s so tragic about this woman, who spends the entire book insisting she’s not a nepo-baby who got where she is because her father is a big-time lobbyist: Her identity is entirely defined by the man she’s bound her fate to. Wealthy, educated, and well-connected, DeRosa could easily move on. Former Cuomo strategist Lis Smith did. Instead, she spends her time seeking vengeance on Cuomo’s supposed enemies. I was genuinely torn between feeling compassion for her obvious unhappiness, rationalized as the self-sacrificing price of public service, and total disgust at the viciousness with which she tries to discredit (and litigate against) the women Cuomo harassed, to their great financial and emotional distress. DeRosa is indemnified by the state, so taxpayers are subsidizing her legal bills, currently at $1.3 million per New York magazine.

The political theorist Judith Shklar analyzed this kind of character disfigurement in her 1982 essay “Putting Cruelty First,” which identified opposition to cruelty as liberalism’s most foundational feature. She concluded that “Valour is generous; it is the obverse of cruelty, which is the expression of cowardice,” and that cruelty “is made easier by hypocrisy and self-deception.” That’s DeRosa in a nutshell.

She may have spent her career preaching a live-by-the-sword, die-by-the-sword ethos. But in What’s Left Unsaid, she just whines about it.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation