Democrats Are Overdue for New Leadership

To mount an opposition under the coming Trump administration, the party needs new ideas—not the same establishment clinging to power.

Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) whispers to Representative Jamie Raskin (D-MD) during a press conference on February 28, 2024 in Washington, DC.

(Samuel Corum / Getty Images)

As the Democratic Party begins the long process of digging out from the 2024 electoral debacle, the list of prescriptions to reinvent the party’s core governing agenda and messaging complex grows longer and longer. But there’s one short-term pressure point in this battle that’s showing some heartening signs of change: the jockeying for leadership positions within the pending 119th Congress.

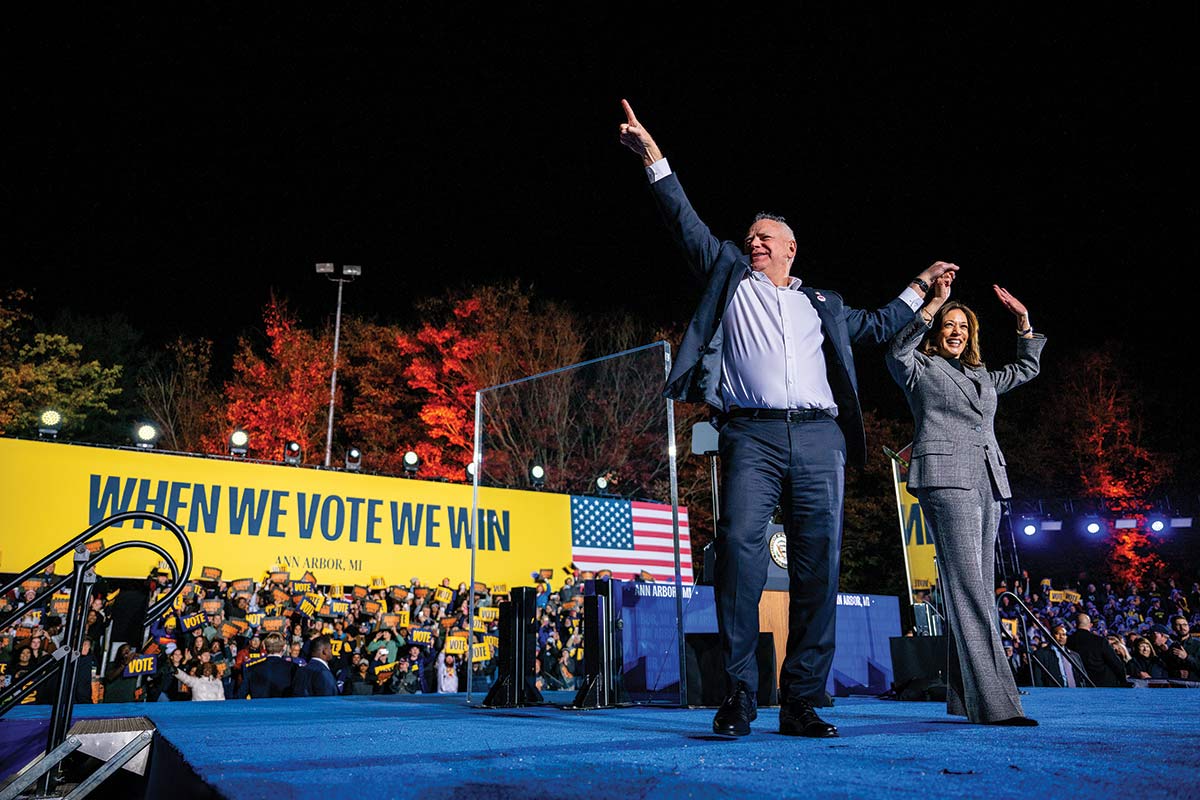

Congressional power struggles aren’t the stuff of marquee ideological showdowns, particularly when a party is continuing its tour in the minority. But as the next House session prepares to launch next month, some important generational and political shifts are already under way. Representative Jamie Raskin of Maryland, 61, has displaced 77-year-old Jerry Nadler as the ranking member on the House Judiciary Committee—and Raskin’s departure as ranking member on the House oversight panel has created another key leadership opening, after he’d leapfrogged the seniority system to become the ranking member there. Thirty-five-year-old Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is hoping to fill Raskin’s slot on Oversight, challenging nine-term Virginia Representative Gerry Connelly, 74, who is battling esophageal cancer. Other House committees, such as Agriculture and Natural Resources, are also poised to see younger members move into ranking positions ahead of leaders with traditional claims to seniority.

This proto-youth movement isn’t a stampede to wrest control of the party away from elder statesman types, but it is a salutary recognition of the need to reinvent the party in basic ways. The House GOP conference imposes term limits on committee leaders; they serve across three sessions, with the party’s Steering and Policy panel issuing waivers for a fourth term. It’s true that this system has produced a great deal of volatility for GOP initiatives in Congress—though it would seem that the party’s broader leadership challenges are ideological rather than structural, with hard-line anti-government groups like the Freedom Caucus exercising de facto veto power over the Republican congressional agenda.

Democrats, by contrast, have been rigidly dedicated to seniority as a key plank of power, both within the House and Senate and across all branches of government. As longtime House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi withstood a challenge to her tenure during the first Trump term, Democrats saw Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and President Joe Biden cleave to power well past their optimal effectiveness in office, with disastrous consequences. Against this backdrop, the present churn in congressional leadership is a welcome departure from form for a party that’s been steadily ossifying into a gerontocracy.

“Democrats have about the best numbers they can hope for as a minority party in the House,” says Matthew Green, a Catholic University political science professor and former Democratic congressional staffer. “They’ve got the ability, if they act as a team, to make things very hard for Donald Trump and his agenda. But it’s not just about numbers. It’s about who those folks in leadership are—what do they represent, and how they appear to voters, as well as the strategies and tactics they embrace.”

In this regard, Raskin and Ocasio-Cortez are particularly striking augurs of change. Raskin leveraged his Oversight post into a leadership role on the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6 Attack on the US Capitol—an investigative body whose members Trump has threatened with criminal prosecution. Ocasio-Cortez has already drawn speculation as a possible 2028 presidential candidate. It’s also worth remembering that her surprise 2018 primary victory represented another sort of blow at the Democratic seniority system, since she defeated incumbent New York Representative Joseph Crowley, whom Pelosi had been grooming as her eventual successor to party leadership.

There’s another broader political lesson worth heeding in a prospective leadership turnover: The modern GOP was similarly spinning its wheels thanks to its long-term minority status on the Hill until a new House leader named Newt Gingrich maneuvered it back into relevance in the early 1990s. Gingrich had used his perch on the House Ethics Committee to target then–Democratic Speaker Jim Wright, on charges relating to book-marketing and real estate deals; after the charges sparked Wright’s resignation, Gingrich was promoted to minority whip. His partisan campaign to unseat Wright served as the model for the 1994 Contract With America that propelled the party to its second majority in more than half a century. Gingrich’s ideological takeover also served as the template for the subsequent Tea Party and MAGA insurgencies on the right, while sanctioning a model of congressional governance that, in marked contrast to the Democratic opposition, frequently discards party leaders the minute they fall out of ideological favor.

Green, author of a study on Gingrich’s career as a party power broker, notes that the former speaker’s rise came about in a political environment a universe or so removed from today’s intensively partisan Congress. “At the time Gingrich was first in the House, in the ’70s and ’80s, it was becoming more partisan, but it was still heavily bipartisan,” he says. “There was this ethos that you don’t attack colleagues on the campaign trail, you don’t use speeches on the floor as a means to get attention. Gingrich described his plan, and I think accurately, as an effort to shift the culture of the party, if not the House, from being, ‘Well, we all work together on appropriations to get things done through compromise. We’re in the minority, after all.’ Yes, you want to win, but what are you going to do? Gingrich’s answer was ‘No, we’re the opposition. We fight for membership on committees, we fight for everything.’”

Raskin and Ocasio-Cortez aren’t likely to serve as the bomb-throwing arbiters of power that Gingrich was—and that’s a good thing. Gingrich’s ballyhooed Republican Revolution soon fell afoul of the GOP conference’s own bitter internal divisions, as well as Gingrich’s own ethical lapses; within four years, he was also forced to resign his speakership. But they can still be effective and innovative prophets of party renewal—even in the realm of media appeals. Green notes that the pair drew widespread social media attention for posting an Instagram live video mocking then–GOP leader Kevin McCarthy’s eight-hour speech before Congress to block passage of a climate bill. “That underscores how these newer incoming ranking members and likely future committee chairs are familiar, and comfortable, with messaging on new media,” Green says. “That might seem superficial and partisan, but it’s strategic in reaching out to new audiences.”

Of course, new message-savvy leaders in Congress won’t instantly resolve the Democrats’ longer-term electoral woes any more than the party’s self-congratulatory consulting class will. But a more nimble and aggressive body of House leaders can at least bring greater focus on a cohesive agenda for the incoming Congress ahead of the 2026 midterms—and a robust Democratic majority in the 119th Congress is an indispensable first step on the path to renewed political relevance. We can only hope that the broader movement-friendly logic behind this early committee maneuvering will extend to next month’s vote on a new chair for the Democratic National Committee—another key pressure point in the Democrats’ effort to rebuild the party from the ground up.