Democrats Have Backed Off of the Culture War. Why Isn’t It Making a Difference?

Only a strong economic message can restore the party’s credibility with the working class.

The Democratic Party is suffering from an image problem. Too many voters, especially among the working class, see the party’s values as out of step with their own.

In an October 2022 poll by Impact Research, 55 percent of likely voters said the Democrats were too extreme or preachy. According to a July 2023 Pew poll, only 32 percent of adults, and fewer of those without a college degree, see the party as uniquely representing their interests. In a Gallup poll conducted in June 2022, just after the US Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade was leaked, nearly half of adults saw the Democrats as too extreme—a 7 percentage point increase over the previous year, and 3 percentage points worse than the Republicans’ score.

Unpopularity with the working class is an especially grave problem; Democrats had already been losing these voters, regardless of their race or ethnicity—a trend that continues to spell electoral doom. It also stands in puzzling contrast to voters’ apparent policy preferences: Medicaid expansion and minimum-wage increases have been widely successful through state referenda, and polling generally finds broad support for left economic policies.

How is it possible that with Dobbs, a far-right president, and blatant Republican attacks on democracy barely in the rearview mirror, it is Democrats who are viewed as the extreme party? So-called “popularist” pundits have claimed that the progressive wing of the party is responsible for this, through its push for radical goals like defunding the police and its use of language they find alienating, like “Latinx”—and that the party would be in the clear if it would simply distance itself from such things.

Progressives, for their part, insist these talking points are not the problem, and that indeed the party could move further left, if only it were willing to do so forcefully and unapologetically.

Resolving this debate over what Democratic politicians should talk about inevitably leads to a basic empirical question: What is it that Democratic politicians actually talk about? To get at this, we at the Center for Working-Class Politics (CWCP) conducted a comprehensive quantitative analysis of Democratic candidates’ messaging in the 2022 midterm elections. What we found was that, while Democrats have unquestionably backed off of polarizing culture-war issues, they have also failed to put forward a strong economic platform to replace them. The result is that Republicans have gotten to fill this void with an image of Democrats as out-of-touch cultural extremists.

Put another way, it is not enough for Democrats to simply avoid controversial issues; they cannot fix their reputation unless they signal a real identification with working-class economic grievances, and a commitment to addressing them.

To analyze Democratic messaging, the CWCP, along with a team of research assistants, scraped the website text of nearly 1,000 Democrats running for House or Senate in the primary or general election in 2022. We documented each candidate’s policy platform, the issues they mentioned, various aspects of their rhetoric, as well as their demographic characteristics and socioeconomic background. We combined all of this with data on their district’s characteristics and electoral outcomes, in order to assess how a candidate’s rhetorical style, policy stances, and class background help or hurt their chances of winning.

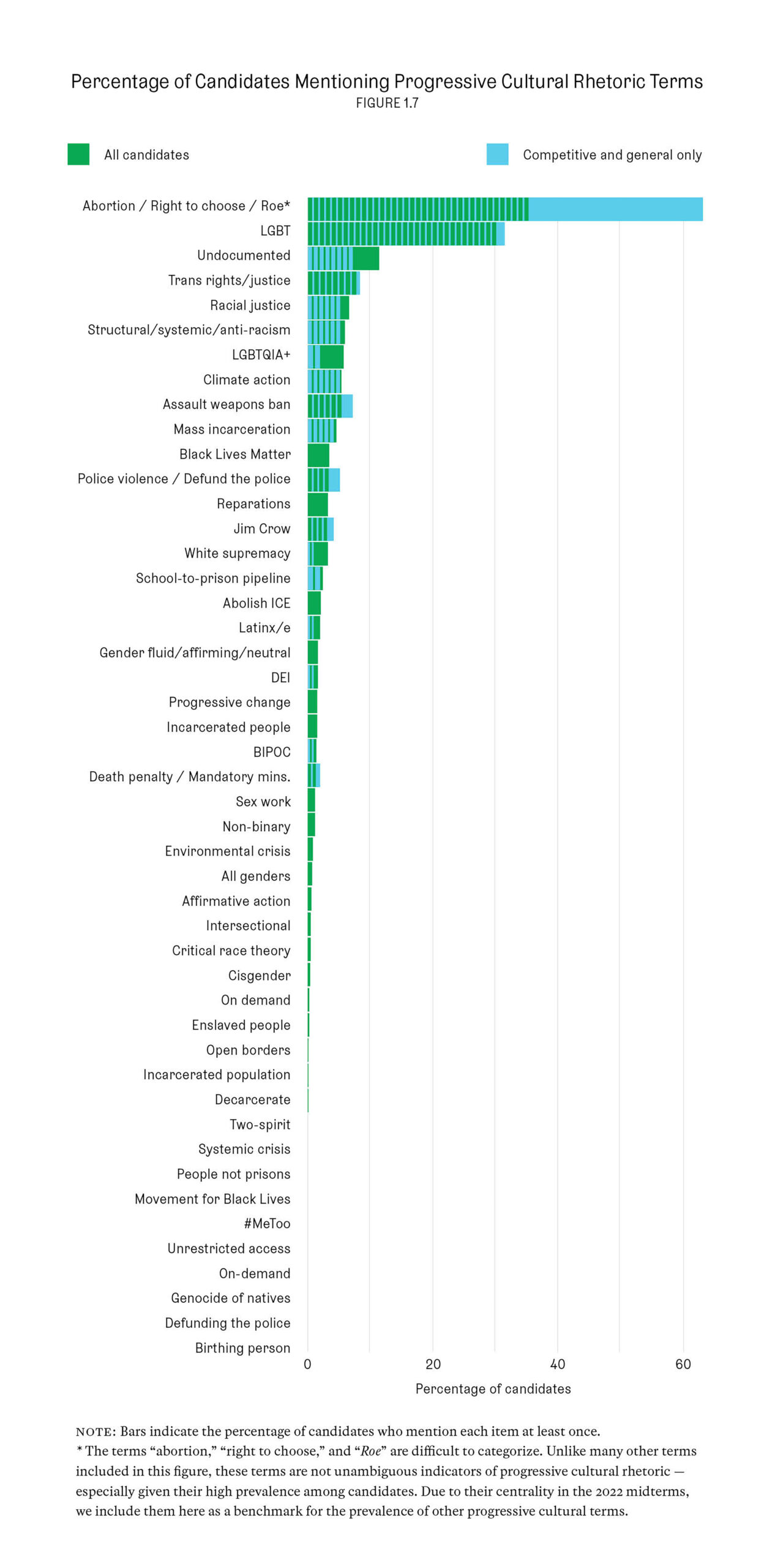

Our study offers many insights, but a few findings on Democratic messaging are particularly salient. To get a sense of what cultural issues Democrats campaigned on, we compiled a list of terms relating to those issues, and tabulated how many Democrats mentioned them. The graph below displays the percentage of Democratic candidates—again, in primaries or generals—who mentioned each term at least once:

A couple facts jump out. For one, Democrats are a far cry from the hopelessly woke political party depicted by so much of the commentariat. Policies and terminology like “abolish ICE,” “Latinx,” and “birthing person” have all but vanished from the Democratic lexicon. “LGBT” came up somewhat frequently, but it is hardly the marker of leftism it might’ve been a decade ago. Simply put, there’s no there there: The progressive wing, such as it is, has mostly fallen into line, and everyone else had never adopted such rhetoric to begin with. The one (arguably) cultural issue that came up frequently, dwarfing all others, was, not surprisingly, abortion rights.

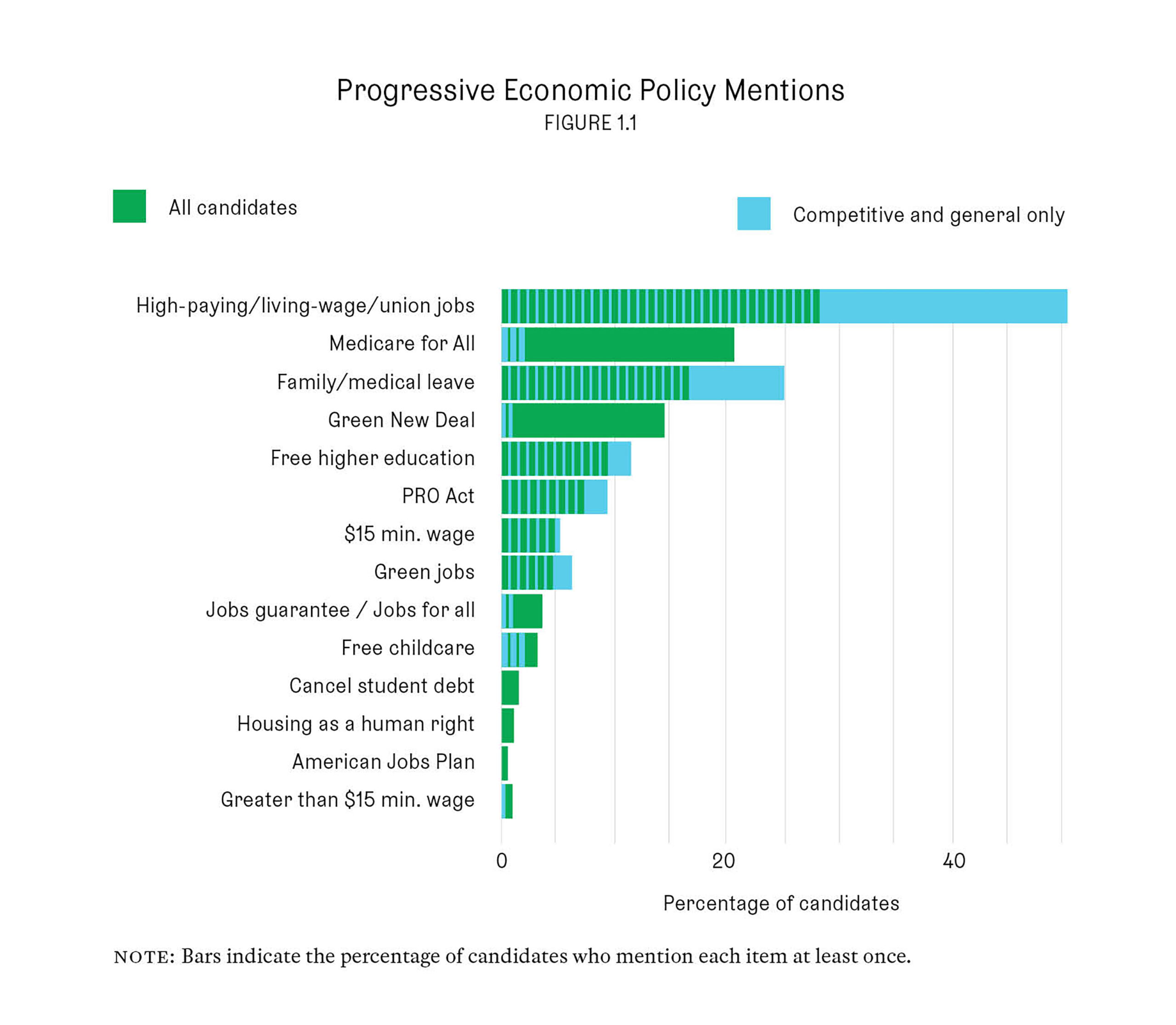

But if it wasn’t these issues, what did Democrats talk about in 2022? We compiled another list of terms, relating to economic issues, to examine what positions Democrats took in that sphere. The graph below displays the results:

As it turns out, on the economy, no policy emerged particularly strongly. Though almost 70 percent of candidates mentioned jobs in at least a generic way, and about half mentioned infrastructure investment, far fewer articulated any sort of bold economic agenda beyond that. Less than a quarter of Democratic candidates talked about Medicare for All, universal free college or childcare, or paid family or medical leave. Only about 5 percent mentioned a $15 minimum wage—one that, in any case, would buy far less at this point than when the Fight for 15 began. Few candidates touted the Democratic Congress’s economic achievements, with only a quarter mentioning the IRA. (A similar analysis that we conducted of candidates’ television ads revealed similar patterns.)

This weakness of policy ambition was reflected in weakness of rhetoric. We tabulated instances in which candidates spoke positively of the working class, and conversely, when they criticized economic elites—together, what we refer to as economic populist rhetoric. While over 70 percent of Democrats praised workers, less than 20 percent called out elites as responsible for economic woes. This is particularly unfortunate, as our analysis found that, consistent with our previous research, anti-economic-elite rhetoric was associated with a larger vote share in highly working-class districts—even after controlling for a variety of important district and candidate characteristics, and across a range of statistical specifications. All told, it appears Democrats have successfully shifted away from the sort of cultural rhetoric that generally turns off working-class voters.

The problem is, no cohesive economic agenda has filled the vacuum left by it—and where there have been wins, they haven’t been emphasized. The party’s failure to call out elites weakens its narrative further, especially against a Republican opponent who can readily (if dishonestly) tap into class-based grievances. Finally, we also found that barely any of the Democrats running in 2022 were working-class themselves. In the face of all this—not to mention a media apparatus champing at the bit for culture-war content, and a right-wing apparatus adept at feeding it—it is all too easy for the popular image of the Democratic Party to remain one of socially distant well-to-dos.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The past several years of intra-Democratic politics have centered on a debate between progressives and popularists. The former, led by the Squad and various advocacy groups, have passionately espoused maximalist left-wing positions on economic and cultural questions. The latter, spearheaded by David Shor and various wonks in the Democratic sphere, have urged the party to abstain from polarizing cultural questions and instead push for low-hanging, incremental improvements to economic policy, in order to win back working-class, non-college-educated voters of all backgrounds. Our study can help to weigh in on this debate—but ultimately, it supports neither and both positions.

The popularists have made an apt diagnosis for what ails Democratic politics: A wealth of evidence supports the view that class dealignment, or education-based polarization, has been exacerbated by Democrats’ emphasis on culture-war debates, that this has cost Democrats working-class voters, and that losing these voters has cost Democrats key elections. That said, the popularist prescription is woefully inadequate. To see why, examine the popularists’ own reading of the situation.

Per their narrative, class dealignment is a deep-seated phenomenon afflicting virtually every industrialized country—the product of decades-long structural transformations in the socioeconomic makeups of electorates worldwide. But if this is so, how are we to believe it will be reversed by a platform whose star attractions are drug-pricing reform and infrastructure spending? The policies in the popularist package are perfectly good, but they are simply not sufficient to transform the image of the Democratic Party from one of socially alien technocrats to workers’ champions. If the popularists have identified an internal hemorrhage, their solution is a Band-Aid.

Nor will it suffice for Democrats to rely on Republican extremism on abortion (or on January 6, and so on) to save us electorally. Dobbs was a powerful cudgel for Democrats in 2022. And in all likelihood, it will be again in 2024. But we should not underestimate the speed with which the political public can become acclimated to a new, worse normal. The sad truth is, the electoral penalties that Republicans will pay for these offenses will inevitably diminish with time.

Democrats can revive their collective image as the defender of workers, but it will take a bolder vision and more aggressive style than they’ve deployed in recent years. This study, together with our previous work, shows that the way to win back working-class voters is through forceful appeals to their economic concerns, in the form of both an ambitious policy agenda and a sharp rhetorical narrative. We hope Democrats take these lessons to heart—or four more years of right-wing destruction may not be far off.