Into the Murk

The Hypocrisies of International Justice

A recent history revisits the Tokyo trial.

The Nazi war crimes tribunal in Nuremberg had already been underway for months by the time its counterpart in Tokyo began in March 1946. The staggered start to these investigations made the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, known colloquially as the “Tokyo trial,” heir to the legal milestones laid in Germany. These included the novel concepts of “crimes against humanity” and “crimes against peace,” as well as the idea that individuals could be held criminally responsible for what had previously been considered acts of state.

Yet the Tokyo trial still had its own legal ground to break. It was “more or less the touchstone for the possibility of organized international justice,” in the words of Dutch judge Bert Röling. Unlike the procedures in Nuremberg, the Tokyo trial could claim to represent a genuine internationalism, with judges and prosecutors not only from the United States, Europe, and the Soviet Union but also from China, India, and the Philippines. Together, the 11 judges overseeing the trial represented a majority of Earth’s population. The case before them would test whether international law, an instrument born out of European conquest and colonization, could become a vehicle for justice for the world at large.

In this respect, the Tokyo trial turned into a disaster. Problems were evident in the very first days. The president of the tribunal, an intemperate Australian named William Webb, never got a handle on the court. The American lead prosecutor, Joseph Keenan, was worse. Prolix and incompetent and visibly suffering from alcoholism, Keenan had a bad habit of running his mouth to the press, including letting it slip that Japan’s emperor had been spared indictment for the sake of political convenience. That was true enough, but it did not exactly help the tribunal’s already fragile claim to legitimacy. Neither was the air of hypocrisy that hung over the proceedings. This was, after all, a war crimes trial that wanted nothing to do with the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, let alone the US firebombing campaign that had killed around 200,000 to 300,000 Japanese civilians.

Less evident to the public but ultimately more damaging, the 11 judges at the trial found themselves irreconcilably divided on the most fundamental issues before them. When the defense challenged the court’s authority in an opening gambit, Webb was unable to wrangle a unified response from his colleagues. He opted instead to delay the court’s answer until it issued its final verdict—two and a half years later. By then, the situation had become so fractious that only six judges managed to pull together to form a majority. Webb, who had alienated almost everyone at that point, insisted on writing a concurring opinion. Three other judges dissented. That included India’s representative on the court, Radhabinod Pal. In a minority opinion that ran over 1,200 pages, Pal not only argued “that each and every one of the accused must be found not guilty” but condemned the Tokyo trial as an exercise in “formalized vengeance.”

Even before Pal’s dissent came in, many of those who wanted the Tokyo trial to succeed had resigned themselves to its failure. British judge William Patrick was calling it a “squalid farce” in communications with his government. In private, the head of the Allied occupation of Japan, Gen. Douglas MacArthur, confessed that he hoped the Tokyo trial might soon be forgotten. More or less, MacArthur got his wish. Nuremberg lives on in memory, print, and film as one of the crowning achievements of international law. Meanwhile, outside Asia, the Tokyo trial has slipped into oblivion.

Judgment at Tokyo: World War II on Trial and the Making of Modern Asia, a recent book by Princeton professor Gary Bass, seeks to recover the Tokyo trial from this memory hole. It is not the first time the trial has been written about in English. But for the first time, Bass—who has also written an award-winning book on how Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon condoned a genocide in East Pakistan—gives Tokyo the kind of epic treatment that Nuremberg has gotten many times over. In a volume with almost 900 pages of text and notes, Bass has assembled a sweeping narrative that moves fluidly from courtroom transcripts to capsule discussions of legal philosophy, to vignettes of judges and diplomats in the Imperial Hotel in central Tokyo, blowing off steam over drinks. The implications of this history are far less tidy than what Nuremberg has been made into. Bass calls the trial “a dive into the murk.” But it is in that murk that we find a much more honest expression of 20th-century international law and American hegemony at the moment of their birth.

Like Nuremberg, the Tokyo trial was conceived as a watershed legal event. Two decades earlier, after the First World War, the British had spearheaded an effort to put Germany’s Wilhelm II on trial, only to have the plan fall apart when the Netherlands, then harboring Wilhelm, refused to extradite him. That left Nuremberg and Tokyo on untrodden ground when it came to international criminal law. There was the novelty of trying high-profile leaders for the atrocities committed under their command. More important, as far as the Allied powers were concerned, there was also the charge that Japan and Germany had waged “aggressive” wars that could not be justified as self-defense, and so were criminal by their very nature.

On both counts, Japan presented a harder case than Germany. Brutality and sexual violence were endemic to Japan’s conquest of Asia. The scale of the atrocities and the uniformity of torture methods suggested some level of coordination. Yet in contrast to the bureaucratic rigor by which the Nazis documented their crimes, there was only a scant paper trail connecting Japanese atrocities to senior leadership. Japanese troops had torched as many records as they could in the last months of the war. In China, the site of some of Japan’s most heinous acts, a civil war between the Communists and the enfeebled Nationalist regime hindered the search for documentation. Decades later, it would come to light that the US government had also covered up its discovery of a biological weapons research center outside of Harbin. In exchange for the research data, the United States shielded the head scientist, Gen. Ishii Shiro, and his underlings from prosecution, thereby hiding evidence that Japan had conducted experiments on thousands of prisoners and intentionally spread plague, cholera, and anthrax through several Chinese cities.

In spite of these obstructions, the prosecutors in Tokyo were still able to make a compelling first pass at documenting some of Japan’s worst atrocities: the Nanjing Massacre, the slaughter of civilians during the Battle of Manila, the hell endured by Allied POWs, who died at a rate of 27 percent in Japanese custody. Bass relates a good portion of this evidence in detail. Conjured up are images of Chinese teenagers raped and murdered by Japanese soldiers; 22 Australian nurses shot in the back as they were marched into the sea; the scars of a former POW who somehow survived an attempted beheading; a diary entry from a Japanese private in the Philippines: “It was hard for me to kill them because they seemed to be good people. Frightful cries of the women and children were horrible. I myself stabbed and killed several persons.”

These accounts shocked the Japanese public. Diplomatic cables showed that several of the defendants in Tokyo, among them Japan’s most senior military and political figures, had known about these crimes and did almost nothing to stop them. Yet whether such complicity was a crime in itself was still an open question at the time of the trial.

More vexing was the charge that Japan had waged an aggressive war. This was the most revolutionary part of the indictments at both the Tokyo and Nuremberg trials, and easily the most contested. For decades, as Asians and Africans knew all too well, war and annexation had been considered perfectly legitimate acts of state under international law. It was true that the ground had shifted since the First World War. Under a new spirit of internationalism, Japan had joined other nations in signing a series of treaties proscribing warfare except in cases of self-defense. After the Covenant for the League of Nations, the most prominent of these treaties was the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact, which renounced war as “an instrument of national policy.” A lofty commitment, no doubt, but there was no consensus on what was or was not an act of aggression, whether these agreements added up to a legal obligation, or whether breaching them was a crime.

Doctrinal issues aside, what made aggressive war tricky to prosecute in Tokyo were the complexities of Japan’s war itself. The prosecution alleged a grand conspiracy for the domination of all of Asia, hatched by a small clique of ultranationalists in the 1920s and carried out over a period of almost 15 years. They could show on a map how, after Japanese troops invaded Manchuria in September 1931, Japan had steadily claimed new territory and widened its conflict. But Japan offered no analogue to the Nazis, let alone a political figure akin to Adolf Hitler. Instead, Japanese politics during these years were vexingly chaotic. Between the invasion of Manchuria and Japan’s surrender in August 1945, the country cycled through 12 different prime ministers; multiple coups were attempted; and Japan’s largest political parties acquiesced to forming a coalition government with the military, itself beset by infighting. In fact, the only leader who remained a constant across these years was Emperor Hirohito. Evidence read in court showed his significant role in the war. But by the time the Tokyo tribunal commenced, MacArthur had become convinced to spare the emperor from prosecution, largely because he seemed useful in selling the Allied occupation to the Japanese public.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The 28 defendants chosen to stand trial received no such clemency. Two-thirds of them were military leaders, the most notorious of whom was Tōjō Hideki. Politicians—a handful of former prime ministers and foreign ministers, along with Emperor Hirohito’s personal adviser, Kido Kōichi—made up the remainder. Originally, the pan-Asianist and Islamic scholar Ōkawa Shūmei had also been included in the indictment, but he was remanded to a psych ward after he started slapping Tōjō’s head during the first day of trial. These men were selected for a variety of reasons, whether because they represented a key moment in the prosecution’s conspiracy narrative or because they were implicated in major atrocities. Looked at as a whole, it was clear the most important criterion was involvement in the decision to attack Pearl Harbor in December 1941. This was the crux of the prosecution’s case and, not coincidentally, Japan’s gravest crime in the eyes of the Americans.

But Pearl Harbor—along with Japan’s near-simultaneous assault on the Philippines, Guam, Wake Island, Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong—also marked the point at which Japan’s war on the Asian mainland exploded into a clash of Pacific empires. Almost every place that Japanese forces attacked from then on was a colonial territory of one kind or another. It was a stretch to claim, as the defense did, that Japan was acting in self-defense and merely responding to the oil embargo the United States had placed on Japan for its occupation of Indochina. But all the denunciations of Japan’s war of conquest during the trial raised a question that the prosecution was not prepared to answer: What gave the United Kingdom, France, the Netherlands, and the United States any more right to control these lands and their people? From that perspective, the charge of “crimes against peace” could look a lot more like a rickety legal barrier erected to keep out newcomers from an imperial game that Western powers had already played to their own advantage.

Here, as in so many other instances throughout the trial, the Western powers wanted to have things both ways. They wanted to indict senior Japanese leaders for a criminal war while reserving the emperor for their own purposes. They wanted to condemn Japan’s assault on civilian populations without opening America’s scorched-earth bombing campaigns to scrutiny. They wanted to indict the defendants for waging a war of conquest while, at that same moment, France and the Netherlands were reasserting their colonial claims in Indochina and Indonesia at gunpoint. In a strictly legal sense, these contradictions may not have undermined the case against the defendants at the Tokyo trial. Crimes don’t cancel each other out, as Bass notes several times. But the cascading hypocrisies did diminish any moral authority the tribunal might have had, leaving the weaknesses of the prosecution’s case all the more evident.

In the end, a bare majority of six judges were able to find common ground in legal minimalism. The judges avoided any broader discussion of international law by upholding only the line established at Nuremberg. The authority for the court, they argued, came from the court’s charter. The Kellogg-Briand Pact established aggressive war as a crime. All of the accused were found guilty; seven would be hanged. Bert Röling of the Netherlands and Henri Bernard of France dissented, largely due to their unwillingness to accept that Japan’s war was a capital crime. The Filipino judge, Delfin Jaranilla, took the opposite approach to a similar outcome: In his concurring opinion, he railed against the excessive leniency of the majority of the sentences and the failure to arraign the emperor. The intemperate Webb also broke with the majority over his belief that the emperor should be held responsible for Japan’s war.

The only judge unfazed by the tumult of these 11th-hour negotiations was Radhabinod Pal. He had spent his entire judicial career working dutifully for the Raj, without any public sign of discontent; but for reasons that Bass can only speculate on (Pal’s family refused access to his personal papers), Pal showed up in Tokyo already preparing to issue a broadside against the tribunal. Having communicated this to his fellow judges at an early date, he passed the rest of the trial in a state of relative calm, writing his dissent at night and reciting Bengali love poetry to himself when he grew bored with the testimony.

The opinion Pal produced represented the most sustained effort among the judges to grapple with the major questions of the trial. That started with its legal validity, which he deftly picked apart before continuing to more consequential matters. As Bass observes, Pal was the only judge to directly confront racism and empire in his opinion. He was the only judge to fully take stock of the hypocrisy that ran through the trial and the new epoch of international law it was meant to inaugurate. In these passages, Pal was devastating. He insisted that the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the only war crimes in the Pacific war that deserved comparison to the horrors of Nazism. He dismissed the moralizing language invoked in the court’s verdict as nothing more than pretense. So long as the “international community” refused to concern itself with the injustice of imperialism, he wrote, “I cannot see how such a community can even pretend that its basis is humanity.”

Had Pal stopped there, his dissent might have been a principled counterpoint to the majority. But Pal went on, over hundreds of pages, to offer a strained apologia for Japan. Parroting Japanese wartime propaganda, he wondered whether Chinese troops might have provoked Japan’s invasion of Manchuria. (They did not.) Pal also went out of his way to impugn the evidence of Japanese atrocities, based on a gut feeling that Chinese witnesses had exaggerated the horrors they experienced in Nanjing. (Later in life, Pal would express similar doubts about the veracity of the accounts given by Holocaust survivors.) As the capstone on this idiosyncratic document, Pal concluded with a weepy passage from Confederate President Jefferson Davis. The gist of it was that, in time, justice “will require much of past censure and praise to change place.”

In a newly independent India, Jawaharlal Nehru was horrified by the position Pal took. Japanese nationalists, on the other hand, thrilled to Pal’s opinion. They took his words as proof that Japan had fought a just war and that the Tokyo trial was nothing but unjustified retribution. Until his death in 1967, Pal allowed himself to be doted on by these figures, who trotted him out to thunderous applause at their galas. The irony was that, by then, the same nationalists who were so passionate about Japanese victimhood had become America’s most stalwart allies in Asia. They took money from the CIA for their campaigns, and they kept the Japanese left and anti-war liberals from interfering too much with the network of bases that the US controlled across Japan. By October 1966, when Pal undertook his last tour of Japan, American bombers were already launching from these airfields, headed toward Vietnam.

Judgment at Tokyo is Bass’s fourth book, but it can be read as a mammoth coda to his first, Stay the Hand of Vengeance, which was published in 2002. In that book, Bass took a comparative approach to war crimes trials—from the unsuccessful attempt to indict Napoleon Bonaparte to what was then still the recent rebirth of international tribunals in the face of the Rwandan genocide and the atrocities committed after the breakup of the former Yugoslavia. All of these trials except for Nuremberg were marred by major failures. Even so, Bass concluded that these trials were the “least awful” option on the table. By shunting the desire for retribution into the confines of the legal process, they offered something better than unchecked cycles of vengeance.

In Judgment at Tokyo, Bass makes the same argument. A Gallup poll conducted just before the Tokyo trial showed that around 13 percent of Americans wanted to kill every Japanese person alive, while a full third believed the Japanese state should be destroyed. In comparison to what we’d now call genocide, Bass suggests that a trial that resulted in only seven men being hanged was not the worst outcome.

But the two decades since his first book seem to have dampened Bass’s satisfaction with his theodicy for international legalism. If the Tokyo trial was better than far more horrible acts of hypothetical retribution, Bass is now more inclined to linger on the trial’s failures: the bottomless hypocrisies, the horrors of the American bombing campaign that preceded it, the racism that loomed over everything. For Bass, the trial captures how the Allied powers, the United States first among them, failed to live up to their professed ideals. “The victorious powers made little effort to scrutinize their own wartime conduct, nor to subject themselves to the same legal standards that they had championed at Tokyo and Nuremberg,” he writes, adding a warning that these failures may come back to haunt us.

There is also a way to interpret the Tokyo trial as something other than the Allies falling short of their purported noble aims. It demonstrated the way that international law, when administered so lopsidedly, serves not only to punish atrocities but also to justify them. The morally inflected legalism on display at the Tokyo trial—the Allies’ insistence that they were fighting not just an enemy but a criminal power—helped convince them that any act committed against this enemy, no matter how heinous, was warranted.

President Harry Truman certainly thought so. In his diary, 20 days before the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, he congratulated himself for not targeting Kyoto. “Even if the Japs are savages, ruthless, merciless and fanatic, we as the leader of the world for the common welfare cannot drop this terrible bomb on the old capital.” Bass zeroes in on the slur “Japs” in this passage, remarking how Truman’s racism blurred the lines between Japanese leaders and civilians. But just as striking are Truman’s invocations of Japan’s ruthlessness and the magnanimity of America’s cause. Seen in this light, the Tokyo trial looks much less antiseptic than Bass portrays it. To the seven men who were sentenced to death, one could add some portion of the hundreds of thousands of people incinerated by US bombs in the final months of the war and the tens of thousands who suffered from radiation exposure long after the war was over.

By the same token, the United States’ unwillingness to reckon with the shambles of the Tokyo trial and the horrors that the US had inflicted on Japan is more than simply a failure to atone. It does its own work: It holds the door open for the United States to do these things again, just as we did in Korea, Vietnam, and Cambodia. And it offers a grim model to the world, not of legalism but of an unspoken right to massacre. Israeli diplomats argued something along these lines when, in the early days after October 7, they pointed to America’s bombing campaign against Japan as a precedent for the kind of mass civilian casualties that Israel had already started to inflict in Gaza. Senator Lindsey Graham picked up on that cue this spring: While discussing US military aid to Israel on Meet the Press, he observed, “We decided to end the war by the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with nuclear weapons, and that was the right decision. Give Israel the bombs they need to end the war.” However crude these analogies are, they are not coincidental. They point to the source of the impunity they invoke—born out of US atrocities in Japan and sanctioned by omission at the Tokyo trial.

What to make of the legal framework that emerged in tandem with this impunity is, it turns out, a more intricate question. For several decades after the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials, it was a nonissue. The vision that inspired these tribunals—of a world in which interstate violence would be regulated by law—was left by the wayside during the Cold War. It was only in the 1990s that the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials were recalled as legal events, to be hammered into precedents for an international justice system based in The Hague. Almost 30 years on, warfare today has become absolutely entangled in law, although in many respects the Tokyo trial is only a distant relative to our current regime. The notion of a criminal war, so central in the wake of World War II, has largely been abandoned in favor of a legal framework that focuses on regulating battlefield conduct and punishing atrocities.

In other ways, however, our international justice system is still mired in the same pretenses and inequities on display at the Tokyo trial. It far more resembles that trial, in any case, than anything that transpired at Nuremberg. International criminal law may speak in a language of universal commands and precepts, but there is still no such thing as equality before it. It has mostly been enforced against Africans, while the United States, China, India, and Russia—each represented on the bench in Tokyo—have either refused to sign or to ratify the 1998 treaty that established the International Criminal Court. The United States has gone furthest of all with its 2002 American Service Members’ Protection Act, pointedly nicknamed the Hague Invasion Act, which allows the use of any means “necessary and appropriate” to free American service members or those of our allies from detention at the behest of the ICC.

Yet this US law, as well as Congress’s June vote to sanction the ICC, also underlines a more heartening feature of international justice. No matter how much pull great power exerts, international law has grown big enough that it still exceeds that power’s control—even if that power is the United States. Moments where the law breaks from the status quo are rare, but they are compelling for that reason. They lay bare, in an exacting and clinical language, the prejudices and hypocrisies of the so-called liberal international order. The fissures that open at these times may suggest to us visions of a different and more just world. But we still entertain those thoughts from down here in the murk.

Support independent journalism that exposes oligarchs and profiteers

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Chuck Schumer’s Flight-Over-Fight Instinct Is Leaving Democrats in the Lurch Chuck Schumer’s Flight-Over-Fight Instinct Is Leaving Democrats in the Lurch

The Senate minority leader appears to think the way to resist the Trump administration is by voting for the GOP’s spending bill.

Ilhan Omar’s American Dream Is Strong Enough for These Times Ilhan Omar’s American Dream Is Strong Enough for These Times

Thirty years after she came to the US, the Minnesota representative keeps the faith in an America that will ultimately reject the divisive politics of Trump and his minions.

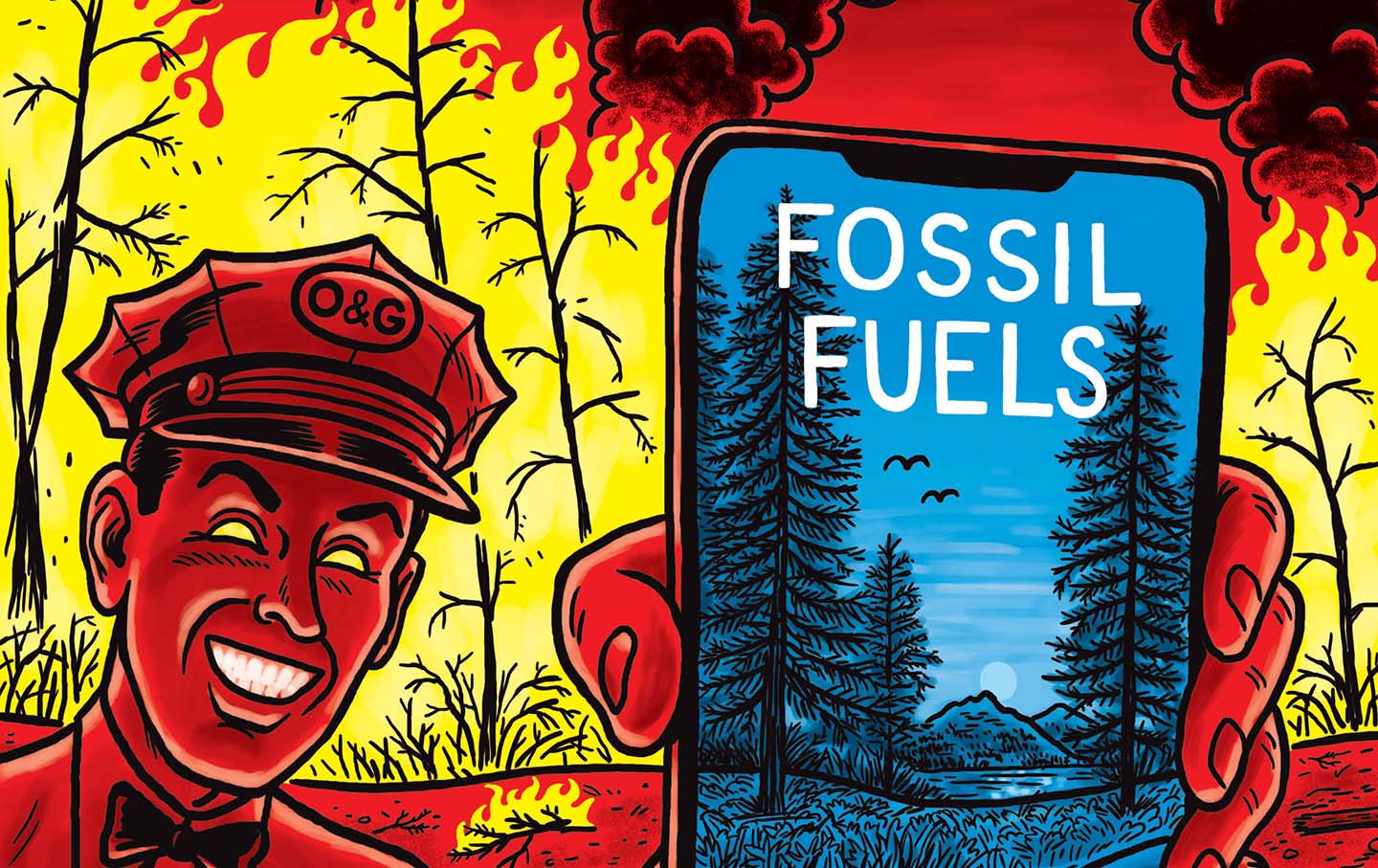

Denying Reality as We Burn Denying Reality as We Burn

Check out all installments in the OppArt series.

Can the Free Press Be Saved? Can the Free Press Be Saved?

It will take a new movement of responsible readers and benefactors to protect independent media.

Is Political Violence Ever Acceptable? Is Political Violence Ever Acceptable?

Natasha Lennard argues that it’s harmful to acquiesce to the state’s determinations of violence, while David Cortright writes that violent acts prevent mass resistance movements.