Today's Republicans aren’t isolationists; they are hawks targeting Latin America and Asia.

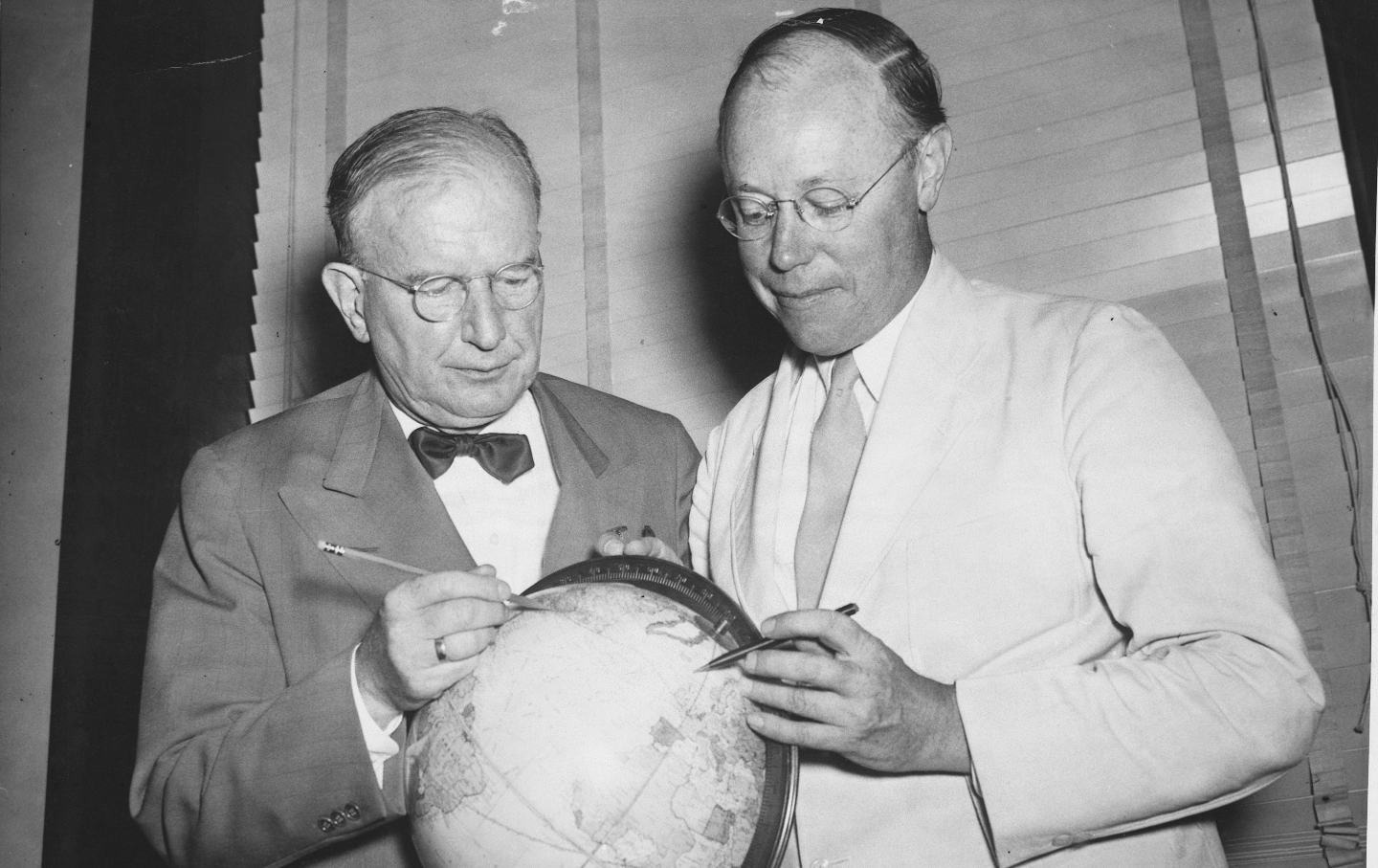

Senators Burton K. Wheeler of Montana and Robert Taft of Ohio study a globe.(Hulton-Deutsch Collection / Corbis via Getty Images)

Speaking to Sky News last month, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen expressed confidence that the United States could “certainly” afford to finance two ongoing military conflicts involving Ukraine and Israel. Yellen was speaking on behalf of the Biden administration, which has yet to see a foreign policy crisis that it doesn’t think can’t be solved with a transfusion of military hardware to allies. As Michael Hirsh noted in Foreign Policy, we are witnessing Joe Biden’s “ambitious—and somewhat scary—attempts to project military strength on three major international fronts: supplying, all at once, Ukraine’s stand against Russia, Israel’s war on Hamas, and Taiwan’s defense against China.”

Biden’s hawkishness is provoking a backlash across the political spectrum. On Israel/Palestine, he is faced with a rising chorus of voices within his own party appalled at the massive scale of civilian death in Gaza caused by Israel’s bombing campaign (which has been underwritten by the financial, military, and diplomatic support of the United States). Not just the familiar left voices like Representatives Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib but even more centrist figures such as Senators Tim Kaine and Dick Durbin are calling for more restraint, with Durbin advocating a cease-fire. In the coming days and weeks, as more and more horrific images from Gaza continue to circulate on the media, Democratic anger at Biden, already evident in massive protest rallies across the country, will increase.

But Biden is also facing intensifying opposition to his strong support for Ukraine from Republicans. Hirsh observes,

The Republican Party, which has been a font of isolationist sentiment for more than a century, is once again splintering over U.S. commitments abroad. Even before Hamas started another war on Oct. 7, the GOP was backing away from Ukraine. Now the new House speaker, Mike Johnson, has opened up a fresh fissure by insisting on sending aid only to Israel for the moment—and making it contingent on domestic budget cuts—while Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell still wants to link that bill to Ukraine aid. But even McConnell now wants to tie this money to new funds for domestic border security.”

Hirsh isn’t the only observer fretting about so-called isolationism among Republicans. Washington Post columnist George Will is also anxious over the GOP’s growing skepticism about supporting Ukraine and worries that if Donald Trump becomes the Republican presidential nominee in 2024, “one of our two major parties will be more isolationist than either party was during the 1930s high tide of ‘America First’ isolationism.” Like Hirsh, Will recognizes that this is a return to an old pattern, citing the pivotal battle in the 1952 Republican primary when the internationalist Dwight Eisenhower vanquished Ohio Senator Robert Taft, the GOP’s leading critic of NATO and the Marshall Plan.

A recent Economist editorial told the same story of the GOP going from the isolationism of the 1930s and ’40s to a long internationalist phase that ran from Eisenhower to George W. Bush and now taking up the cry of “America First!” again. According to the British newsweekly, “In place of a foreign policy that saw America as a protector of freedom and democracy is a new doctrine of America First that shuns allies (barring Israel) and would give up on the Ukrainians fighting off a Russian invasion, even when no American soldiers are at risk.”

This narrative of isolationism as the return to the repressed is broadly accurate. Donald Trump’s wariness of NATO and entangling alliances certainly puts him closer in spirit to Charles Lindbergh and Robert Taft than to Republican presidents from Eisenhower to Bush Jr.

The problem with this narrative is that the phrase “isolationist” obscures the actual politics of America First, both past and present. The parenthetical “(barring Israel)” used by The Economist is an important clue. The proviso is inadequate. It’s true that very few Republicans are isolationist when it comes to Israel (although Kentucky Senator Rand Paul warned that the Israeli response risked creating “blowback” and “moral chaos”). Rather, Republicans are even more likely to back full-throttle support of Israeli militarism. Further, Trump and other MAGA Republicans are increasingly advocating a militarized approach to American-Mexican relations, with calls to invade Mexico in order to deal with the supposed threat of drug cartels. Further, America First Republicans are not isolationists when it comes to the second-largest country in the world, China. Rather, under Trump, hawkishness about China has become the norm, with not just trade wars but also the threat of regime change (voiced in 2020 by then–Secretary of State Mike Pompeo).

So Republicans can be fairly called isolationist—except when it comes to Israel, Mexico, and China. Those are massive provisos and make the very term “isolationism” seem ridiculous.

In fact, isolationist has never been a good description of America First foreign policy, whether in the 1930s, the ’40s, or the 21st century. As Hirsh acknowledges in citing scholar Stephen Wertheim’s work, isolationism was “a pejorative invented by internationalists to shame the America Firsters into silence.… the United States has always sought some engagement abroad, at least through trade.” It should also be noted that isolationist is often a pejorative used by centrists and establishment liberals to discredit anti-war left-wing voices like George McGovern, Jesse Jackson, and Bernie Sanders. The term is so loaded with false assumptions that it should be discarded.

Rather than being isolationist, the Republican formula is disengagement from Europe and focusing on dominating Latin America and Asia.

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation

As it happens, this foreign policy profile is very similar to the geopolitics of the America First Republicans of the 1930s and ‘19’40s such as Herbert Hoover, Douglas MacArthur, Charles Lindbergh and Robert Taft.

In their 1951 book The General and the President, about the struggles between Douglas MacArthur and Harry Truman, journalist Richard Rovere and historian Arthur Schlesinger noted:

The Pacific Ocean has become in this century the Republican ocean; the Atlantic, the Democratic ocean. When the Republicans have had a foreign policy at all, it has generally been something to do with Japan and China; they are the party of the eastward orientation. The Democratic presidents in the twentieth century, on the other hand, have stood for an affirmative policy toward Europe (as they have also stood—from the Republican viewpoint—for the application of subversive European theories to the American economy).

In the 21st century as well, this division of the parties along oceanic lines has returned, with Republicans looking toward Asia, and Democrats oriented toward Europe.

The Republican lean towards Asia has many roots: the evangelical missionary zeal for new converts, the business class’s desire for new markets, the racist view that the supposed Yellow Peril needs to be subdued, and long-held geopolitical theories about the need to dominate the Pacific.

Elizabeth N. Saunders, an international relations scholar at Georgetown University, takes up the continuity of America First from the 1930s to the present in her forthcoming book The Insiders’ Game: How Elites Make War and Peace. In a recent interview with me, she brought up an arcane word from the 1950s: asialationist. As Saunders told me, it’s a word that is “very hard to say.” An editor at Princeton University press even asked Saunders if that was a real word.

But strange as it sounds, asialationist describes the actual politics of Robert Taft and his cohort. They were wary of European wars and were even willing to let Hitler rule as overlord of Europe. But they wanted the United States to dominate the Western Hemisphere and expand its sphere of power into Asia. According to Saunders, some asialationists, notably Taft, had a sincere ideology. Others, like Louis Johnson, Harry Truman’s secretary of defense from 1949 to ’50, were “cost cutters” who opportunistically used the Korean war as a “cudgel” to push for their real policy goal, less spending on European defense. Another subset of America Firsters was hybrid figures like Joseph McCarthy who had some sincere convictions but also used the alleged failures of Truman in Asia as a way to outflank the Democrats on anti-communism.

Saunders believes the same mixture of true believers and opportunists can be seen today. Trump does seem genuinely committed to some form of America First, going back in decades. Once Trump won the GOP nomination and election in 2016, he was able to remake the party in his image because countless opportunists wanted to emulate him. Saunders observes, “Trump showed what power the presidency has to completely change the direction of a party.” Prior to Trump, America First was a minority tradition that showed up in the odd protest candidate, notably Ross Perot and Pat Buchanan. Now, it’s the dominant strand of the GOP, although a position often only cynically held.

The America First tradition has often been treated with scorn by establishment critics. Much in this tradition, notably the unwillingness to fight fascism in the 1930s and early ’40s, is indefensible. Like many other traditions, however, it has gradations and unexpected pertinence.

Get unlimited access: $9.50 for six months.

Robert Taft was, to put it as mildly as possible, a far more serious thinker and political actor than Donald Trump.

In 1949, Taft warned that the formation of NATO violated the principles of the United Nations Charter. According to Taft:

An undertaking by the most powerful nation in the world to arm half the world against the other half goes far beyond any “right of collective defense if an armed attacked occurs.” It violates the whole spirit of the United Nation’s Charter.… The Atlantic Pact moves in exactly the opposite direction from the purposes of the charter and makes a farce of further efforts to secure international justice through law and justice. It necessarily divides the world into two armed camps.… This treaty, therefore, means inevitably an armament race, and armament races in the past have led to war.

These words are remarkable prescient and apply with force to the NATO expansion undertaken after the end of the Cold War by both Democrats and Republicans.

An America First politics that was as thoughtful as Taft’s would be welcome—particularly when centrists Democrats like Joe Biden are supporting conflicts around the world. But a Taftian America First policy is not in the cards for many reasons. The 21st-century Republican Party has no figures who possesses anything comparable to the intellectual rigor of Taft. In his writing on foreign policy, Taft displayed an instinctive distrust of militarism, a respect for global public opinion, and a desire for the United States to live by the rules of prudence and moderation. Trumpian America First—seen in not just the former president but also figures like Mike Pompeo, Ron DeSantis, and Vivek Ramaswamy—offers jingoism, a disdain for diplomacy, a contempt for the concept of international law, and openly unabashed militarism.

What Trump offers is the worst side of America First—a politics of xenophobia underwritten by settler colonialist assumptions. Trumpian America First believes it’s wrong for white nations to fight each other when the goal should be to dominate other races.

But even if the Taftian America First could somehow be revived, it still wouldn’t be a good fit for the 21st century. We live in a much more interdependent world than the early 20th century. The problems that we face in this century —climate change most of all, but also global pandemics, mass migration of refugees, and the need to maintain international supply chains—require international cooperation on a scale we’ve never seen before.

We desperately need an alternative to the militaristic centrism of Joe Biden. But Trump’s America First is just a recipe for more wars. Whatever wisdom we can glean from the writings of Robert Taft have to be offset by the realization that even the best version of America First has little to say about our most crucial problems. The only real alternative is left-wing internationalism.

Jeet HeerTwitterJeet Heer is a national affairs correspondent for The Nation and host of the weekly Nation podcast, The Time of Monsters. He also pens the monthly column “Morbid Symptoms.” The author of In Love with Art: Francoise Mouly’s Adventures in Comics with Art Spiegelman (2013) and Sweet Lechery: Reviews, Essays and Profiles (2014), Heer has written for numerous publications, including The New Yorker, The Paris Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, The American Prospect, The Guardian, The New Republic, and The Boston Globe.