The Harris Campaign Needs to Name Other Culprits Besides Donald Trump

By not naming those responsible for the economic woes that still plague working Americans, Democrats lack a credible story about what they’re going to change—and who is to blame.

When I was a criminal defense attorney, I learned that if you’re trying to overturn a conviction, it’s good to have a strong argument about why your client didn’t do it. But the strongest argument by far—if it’s even remotely possible—is to make the case that someone else actually did do it. Having another culprit is ten times better than an alibi.

Who caused this calamity? Who knifed that man we see splayed out on the car? Who stole the money? The human desire for blame when horrific things happen is so hardwired that when my first-grader stumbles and falls, he’ll sometimes turn accusingly and yell that I tripped him on purpose. Truly bad things, the human brain wants to tell us, cannot be random—since that implies they could happen again, and we’re not safe. Better even to have a parent purposely harm you, apparently, than to live in a world filled with random terror.

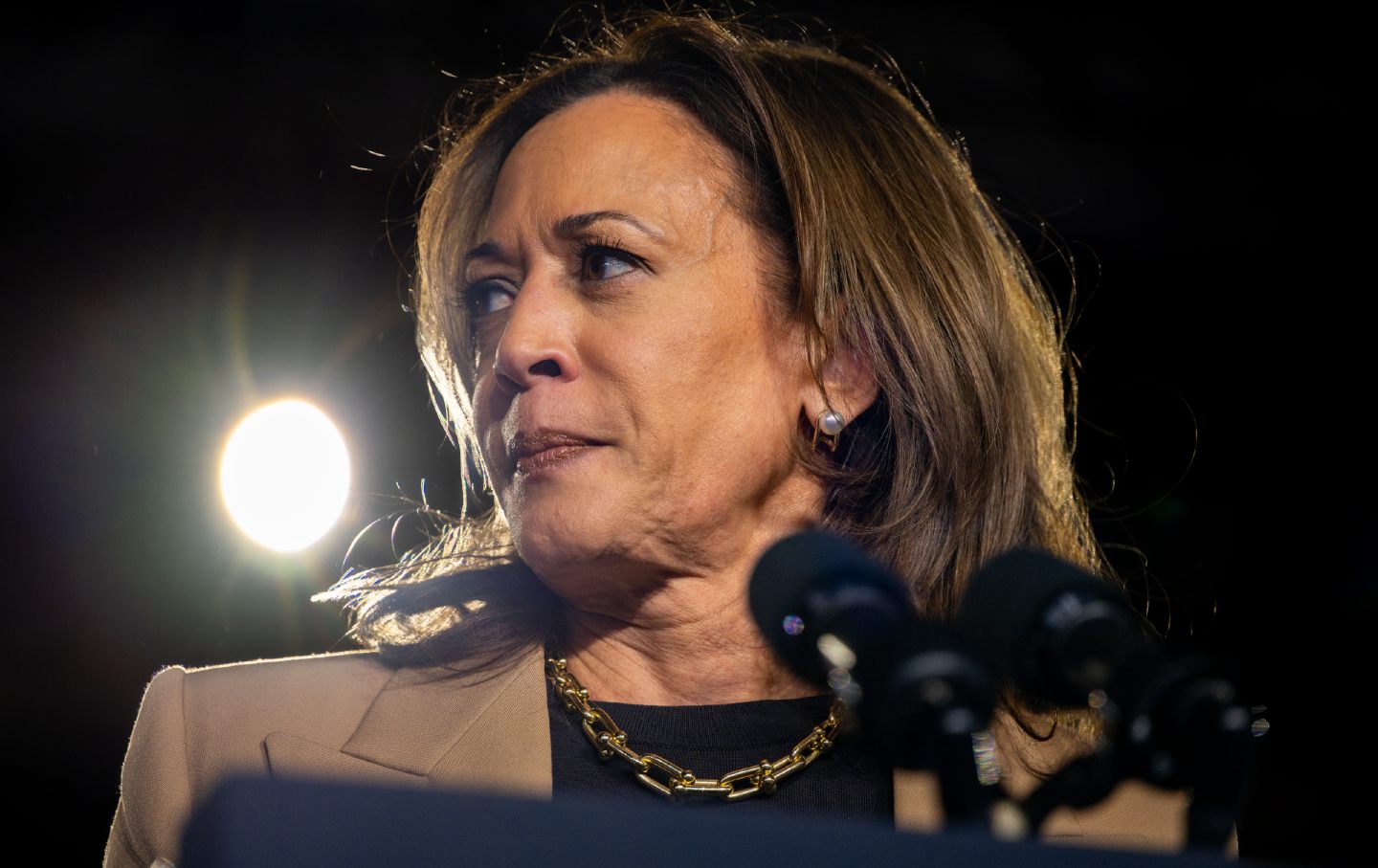

When I try to understand why, despite her many appealing characteristics, Kamala Harris is still struggling to decisively break through to uncertain voters against such a flawed opponent, this basic human need for identifying a culprit helps explain it.

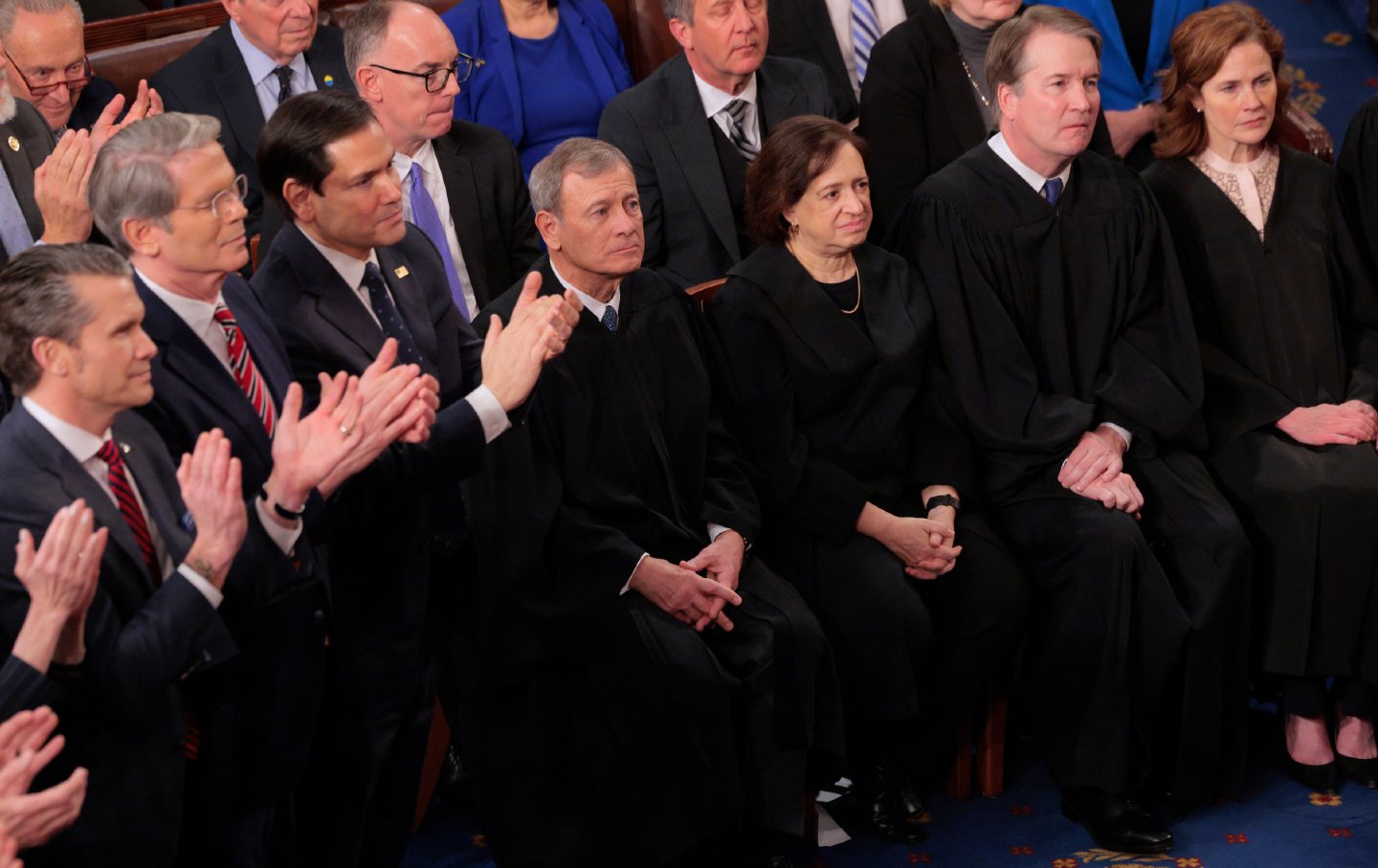

Harris does well on abortion, for instance, where she has a crystal clear story about who caused women’s current loss of access to health care: the Supreme Court and Donald Trump. It was Trump who caused that woman to bleed out in the back seat of her car because he appointed justices who made abortion unsafe. That Harris doesn’t actually have a clear path to reinstate abortion rights—given the composition of the Supreme Court and the likely makeup of Congress—turns out to be less important to people than the way her account allows them to make sense of the recent past.

But on the economy, Harris is in the opposite position. She offers policy after policy in big speeches—many of them both progressive and practical—without ever telling the story of who caused the problem that made such policies so desperately needed. And when she does try to blame Trump for people’s economic distress, her story doesn’t fit with people’s experience, because the 2016 election or Covid didn’t feel like the start of the problem.

The recent Harris-Walz rural policy rollout exemplified this problem to me. It included some excellent elements (like supporting local pharmacies, protecting against land consolidation), but the whole story lacked a villain. “Here’s some good ideas!” the policy suggests, “for a problem no one caused!” Which means it doesn’t speak directly to rural rage at the Big Agriculture monopolists who stole farmers’ wealth, and the CVS and Walgreens chains who destroyed locally owned pharmacies. Those same policies, wrapped in righteous—and accurately targeted—anger, would go much further, because that would tell rural voters that Harris understood where their suffering came from—and therefore understood what it would take to help.

The campaign’s evident desire to win this election on their plans for the future—without ever telling a story about why many people’s lives are so crummy—seems ill-advised. Trump’s bigotry and racism and mean-spiritedness is rooted in a cancerous approach toward blame, of course, but the best rejoinder is not to ignore his travesty of the past but to tell a true story about it, instead of a false one.

This lack of clarity about culprits is one of the key reasons, when it comes to the economy, a lot of voters prefer Trump. Orwell was right about political language—there is a tendency to deploy “phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated hen-house.” When you leave out who did what to whom, you lose the building blocks of politics. The language of “We will fight for you” just sounds confusing if you don’t name the opponent. We will fight [somebody] for you? We will strike our swords into the fog and hope it hits “he who shall not be named”?

The good news is that Harris still has time to add villains who are not Trump to her final closing arguments. She can talk about NAFTA and Chinese rule-breaking on trade. She can talk about Big Ag and Big Oil. She can talk about how big donors and dark money have taken over too much of our democracy. She can tell the public that stagnant wages and high housing prices were not just an act of nature, but the result of greedy profiteering corporations.

Such a narrative may sound depressing, but actually acknowledging cause and effect offers a far deeper source of hope than failing to do so. According to academic research on optimism and “explanatory style,” people who identify “external, temporary, and specific causes” are far more likely to be hopeful than those who think a problem is permanent, or can’t make sense of why they are hurt. Or, to put it in Harris language, identifying non-Trump villains can be a source of joy.

On the other hand, if Harris doesn’t identify the culprits, she’ll have a hard time winning more trust on the economy—the issue voters care most about. That fact might be frustrating to those of us who can recognize all the economic progress made by the last administration. For my money, Joe Biden is the best president on the economy in 50 years, and I can rattle off his numbers on jobs and small businesses and labor as if I worked in his press shop. But “things are inching toward a little better” is not a winning argument, because it still doesn’t address 40 years of stagnant wages (thanks to ultra-globalization and monopoly power), the spiking price of eggs (caused by corporate concentration and greed), and the collapse of small businesses (a consequence of what I call the “chickenization” of retail, food production and more). Yes, these are starting to turn around—look at the 18 million-plus new small businesses since Biden took office—but we aren’t ready to stop pointing fingers yet!

I was at a conference about a decade ago with a very fancy, well-respected Democratic strategist, and someone in the crowd asked him why wages were bad. He said that was the wrong question; the question is what we were going to do about it versus what the Republicans were going to do about it.

That attitude is precisely why what should be a landslide election is currently too close to call. There are bad questions in our political life, to be sure, but “whodunnit?” is not one of them.

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation