Grassroots Groups Know How to Win This Campaign—Do They Have What They Need to Pull It Off?

The Harris-Walz campaign needs every vote it can get. But the groups that do best at reaching every voter have, until recently, been underfunded this cycle, and need more support.

With Election Day less than a week away, we face a stark choice between democracy and dictatorship. Polls in the seven battleground states—Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, North Carolina, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—remain extremely close. Who wins, and by how much, will come down to the strength of each campaign’s ground game. Unfortunately, while the Harris campaign has a great deal of money, the grassroots groups most effective in turning out voters for Democrats do not.

Given the stakes, campaigns can’t afford to overlook a single voter. Hillary Clinton lost Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin in 2016 in part by taking voters in those states for granted. As the number of registered Independents and crossover voters grows, campaigns have to do all they can to give lower propensity, disaffected, and new voters a good reason to show up for their candidate. But the campaigns themselves are often not best positioned to engage with specific communities, especially those that feel unseen. For instance, given legitimate fury over the Biden administration’s unmitigated support for Israel’s war on Gaza, the campaign is far less suited than trusted community leaders to argue that Muslim and Arab Americans should vote for Harris. And those leaders might well be inclined to see a vote for Harris as a “chess move,” in the words of Working Families Party National Director, Maurice Mitchell, “not a love letter”—an approach that underscores they will continue to press for change.

Money is a necessary but not sufficient condition for an effective ground game. The Harris-Walz campaign raised more than one billion dollars, (including funds raised by affiliated PACs) in the abbreviated first quarter of her campaign (the third quarter of this year). The Trump campaign, Republican National Committee, and PACs raised roughly $417 million. At the end of September, Harris had about $350 million left to spend to Trump’s $287 million. There’s a lot of money being spent.

For both major political parties, the ground game is focused on a transaction: Lay out your agenda and get people to vote for it, whether or not that agenda really speaks to the priorities or ambitions of a given community. Campaign staff are sent to states, local offices rented, and a tidal wave of ads, fliers, calls, texts, TikToks, and door-knocks are deployed to convince people to vote. After the election, the offices close, the staff leave, and the outreach is over. It’s not that these campaigns are superfluous; they are simply not enough.

While the amount of money spent does not per se determine the quality of a campaign’s ground game, several news reports (including those by CBS, the New York Times, The Guardian, and The American Prospect) agree that Harris’s ground operation seems far better than that of Trump-Vance. In late September, for example, several Republican strategists lamented Trump’s “paltry get-out-the-vote effort” and “untested strategy of leaning on outside groups to help do field work.” And reporting on America PAC, a separate field operation funded by Elon Musk, has found that it is beset by mismanagement and potential fraud.

Yet “better” does not necessarily mean good or effective. An analysis by Priorities USA of spending by Democrats in the 2020 election found that “while Democrats outspent Republicans, [they were] not spending smart enough to maximize our chances of winning elections moving forward.” The Democratic Party and the Biden campaign spent more on traditional media than on digital, even though Americans get much of their news—for better or worse—from numerous online sources. A lot of what campaigns raise is spent on TV, which is increasingly inefficient, a lot is spent too late in the campaign, and substantial sums are often spent targeting people who have already voted. Moreover, while there are some stellar state parties like Wisconsin Dems led by Ben Wikler, most state parties are underfunded and some very disorganized, which further undermines a campaign’s ground game.

If election campaigns are by their nature transactional, the work of organizers is intended to be transformational. These groups, deeply rooted in their communities, work year-round to build lasting relationships with, and, critically, the collective long-term power of their communities so they can advocate for their own priorities at the local, state, and national levels beyond any single election or any specific elected official. While they often work with the official party infrastructure, they can’t be compromised by becoming part of it because that would defeat the purpose of independence and compromise their later advocacy.

Still, progressive organizing absolutely benefits Democrats, even when the party is far behind the movement in terms of its policy positions. In 2020, progressive groups left it all on the field to elect Biden despite being wary of his past positions on issues like abortion. A decade-plus of investments in movement-building, civic education, and turnout work of independent, progressive grassroots organizations, also led to wins in numerous states. One example was the election of Democratic Governor Tony Evers in 2018, and the successful first step toward taking back the Wisconsin Supreme Court in April 2020.

Concerted efforts by both national groups, such as Asian Americans Advancing Justice, and state-level organizations, like Arizona Asian American Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Advocates (AZ AANHPI Advocates) in Phoenix, led to a dramatic increase of more than 20 percent in AANHPI voting in 2020 over 2016, especially in key states like Arizona and Georgia, where the Asian American share of the total population is growing quickly. A coalition of Georgia groups representing everyone from domestic workers to Black farmers to college students to Asian and Muslim Americans and everyone in between not only won Georgia for Biden but turned around to face a runoff and send two Democratic senators to Washington.

Emgage, an umbrella group that works to increase political literacy and civic participation of the Muslim community, turned out a million Muslim voters across the country in 2020. Milwaukee-based Leaders Igniting Transformation used their ongoing connections to and deep work with high school and college students over several years to turn out record numbers of young voters in Wisconsin, while Voces de la Frontera galvanized Latino communities. During the pandemic, the Hmong American Women’s Association provided pho and other food and supplies to Hmong, Chin, and Karen populations in Madison and Milwaukee while using culturally and linguistically relevant materials to conduct civic education and register voters. These efforts, replicated across the country, increased voter registration and turnout among many new and infrequent voters rarely ever touched by campaigns, which in any case are not trusted in the same way as deeply familiar community organizers. And they made the difference in states like Georgia and Wisconsin that Democrats won by only several thousand votes.

Community groups are trusted sources of civic education, which has declined precipitously in the United States. Angela Lang, Executive Director of Black Leaders Organizing Communities (BLOC) in Milwaukee, Wisconsin told me that they are in the community all year long, to ensure that community members know what’s going on in their city and county budget process, how to lobby the school board or the county council, how to ask for meetings, which ballot initiatives are critical and why, and, critically, what these mean for their own families. “Because we build year-round relationships, even people who are tapped out or disengaged for whatever reason will open the door for us. And among the things we do is civic education, like ‘what does a U.S. Senator do and why should you care?’ If we want people to really start to be engaged, we need to build that civic muscle to vote on a more regular basis, by doing the work that is required year-round.” In fact, she told me, “people often tell our organizers they were looking forward to seeing them.”

These local groups also are first on the scene in disasters. Hurricane Helene devasted communities across North Carolina, a state that is also critical to both presidential campaigns. One organizer who asked not to be named told me that not only were plans for voter outreach conducted by and for food service workers in the greater Asheville area completely dashed by the hurricane, so were their jobs. “October is, or was, a big money month for restaurant workers [because] tourists [normally] flock into Asheville for leaf season,” the organizer told me. But since Hurricane Helene left the region without water and restaurants were demolished, the workers had no income until disaster relief checks started to flow. All these workers could count on was “some FEMA relief.” Unsurprisingly, the organizer expected that voting and organizing other voters would be a lower priority for these already economically vulnerable workers without a good deal of help. Community groups like Down Home Carolina, an organization focused on organizing poor and working-class rural communities, were the first to step in with help and to make sure people can vote.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Down Home and partner groups across the state are also best poised to address the conspiracy theories about FEMA and federal assistance spread by the Trump campaign. “In general, people here don’t have a lot of trust,” Jillian Johnson, Southern Regional Field Director at Movement Voter Project (MVP), told me recently in a phone call. “There’s an anti-institutional feeling and lots of misinformation and disinformation floating out there. So having an organization like Down Home that they already know and has been in the community for years or decades makes a huge difference in connecting people with what they need and later working on getting them to vote.” Movement Voter Project channels donor funds into local organizing groups to build political power and transform policy.

And community groups are often more willing and able to quickly tackle misinformation than the Democratic Party has proven to be. For example, when Trump and Vance launched their vile attacks on Haitian residents in Springfield, Ohio, many in the community assumed the Democratic Party would respond quickly and forcefully. But neither Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown nor Vice President Harris spoke out initially (although President Biden did later condemn the hate campaign). The initial silence led to anger, and then action, said Movement Voter Project’s Senior State Strategy Director, Javier Morillo on a briefing call for supporters. A coalition of Ohio organizers including Ohio Voice, Red Wine and Blue, and Ohio Organizing Collaborative worked with MVP to create the “Oh, No You Don’t” campaign, forcefully pushing back on the Republican conspiracies and bringing community members together well before any Democrat took action.

Powerful organizing groups exist in every state, from Maine, to Montana, Mississippi, Alabama, Texas, and Utah, working daily, often with little visibility, to build power and produce wins. In addition to organizing, they are critical to curing ballots, fighting efforts to purge voters, informing communities about last-minute changes in voting locations, providing childcare, and giving people rides.

But for a variety of reasons, with just a week to go in an election that may prove to be more violent than the last, these groups face a funding shortfall which, as of October 1, stood at over $100 million. Why the gap in this election cycle? Unfortunately, too many donors seem to have been swayed by attacks on DEI and the backlash to campaigns to end police violence in vulnerable communities, along with efforts to slander groups concerned for the human rights of Palestinians as terrorists. Islamophobia seems to be the last form of acceptable racism, and this has led to reduced outside support for Muslim organizing across the country. Several leaders of organizations working in Black and Brown communities have told me off the record that they lost funding because their support for the human rights of Palestinians has been equated with terrorism. And inasmuch as the work these groups do every day is essential to free and fair elections and our democracy itself, they can’t operate if they don’t have freedom of speech.

More money has flowed to these groups since the beginning of October, but it’s coming in very late in the cycle, the gaps are still not closed, and some of the most critical deeper canvassing work has had to be put aside or supported by non-partisan dollars, which undermines the groups’ ability to advocate for Democrats in these last weeks. Win or lose, these trends and the relatively modest support for organizing in vulnerable communities is not good for this election nor for democracy itself. My hope is that next time we see a spate of huge fundraising calls for a candidate, at least one quarter of that money goes straight to the grassroots.

Democracy is an everyday practice and is about far more than voting. If we truly want to strengthen and expand our democracy and rescue this country from fascism, we need to invest in the organizing we don’t see, the less glamorous but crucial work done in every state by organizations with deep ties to communities. These groups need money for their work all year and even more so in an election cycle.

It’s not too late to get funds to them now. You can help immediately by donating to MVP’s PAC, which will get money directly to groups where needed.

More from The Nation

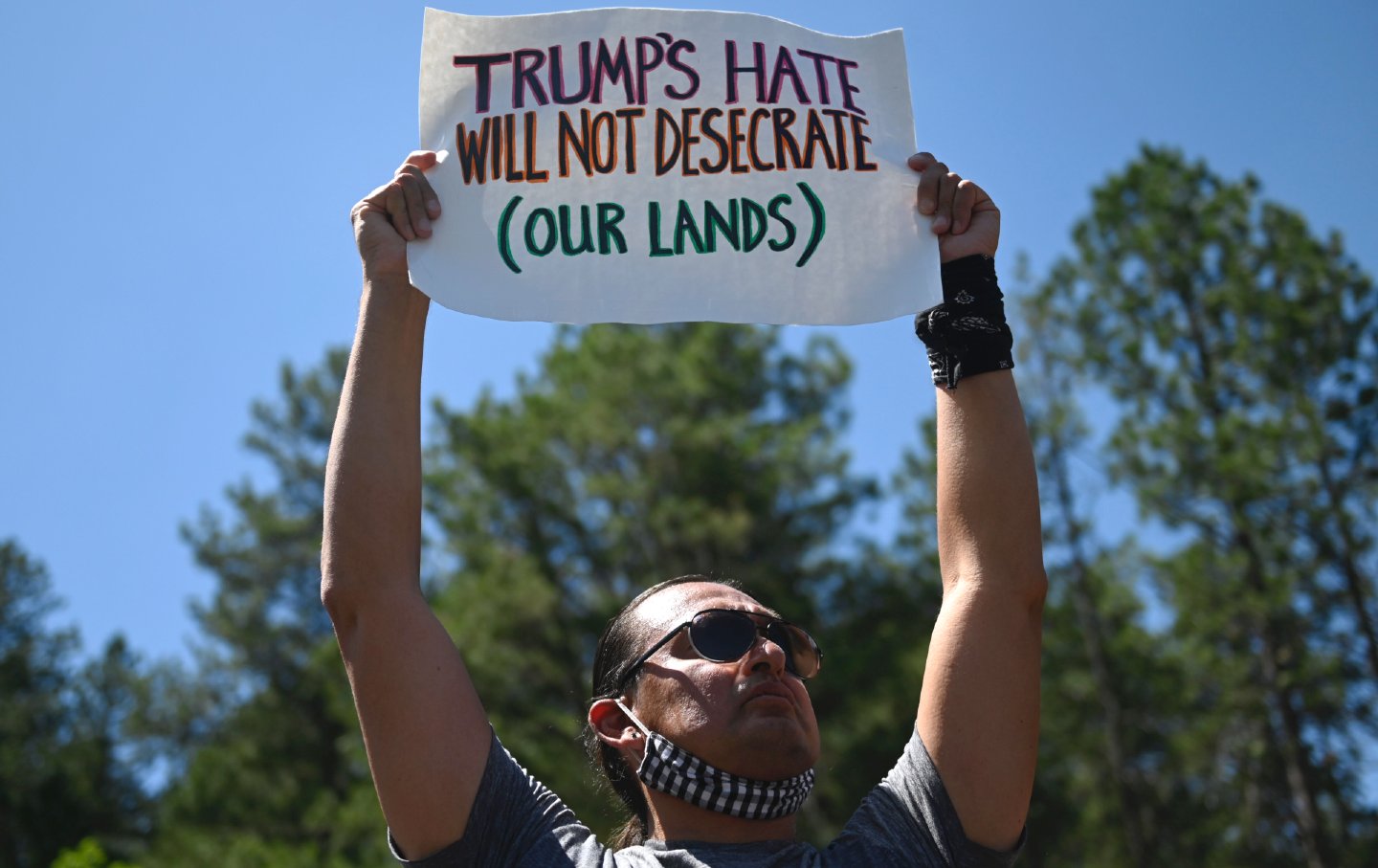

Trump Can’t Strip Natives of Our US Citizenship, but He Will Try to Take Our Lands Trump Can’t Strip Natives of Our US Citizenship, but He Will Try to Take Our Lands

The Department of Justice recently argued that birthright citizenship does not apply to Native Americans. The administration will likely take aim at Native sovereignty next.

Nazis and Racists and “Big Balls,” Oh My! Nazis and Racists and “Big Balls,” Oh My!

Elon Musk’s DOGE-boys are hacking our government. The misogynist bros of the 2014 Gamergate travesty have won. For now.

It’s Time for the Democrats to Throw Off the Dead Hand of Clintonism It’s Time for the Democrats to Throw Off the Dead Hand of Clintonism

More than 20 years after Bill Clinton left office, Democrats remain in the grips of his New Democrat politics. That’s a serious problem.

How Trump Could Remake the Supreme Court for a Generation How Trump Could Remake the Supreme Court for a Generation

Donald Trump is poised to become the first president since FDR to have appointed the majority of high-court justices. His potential picks are terrifying.

The Democrats’ Choice: Fight Trump’s Oligarchy or Keep Groveling to Billionaire Donors The Democrats’ Choice: Fight Trump’s Oligarchy or Keep Groveling to Billionaire Donors

Elon Musk’s power grab is finally energizing a resistance. But it’s already being undermined by the party elite’s dependency on Silicon Valley.