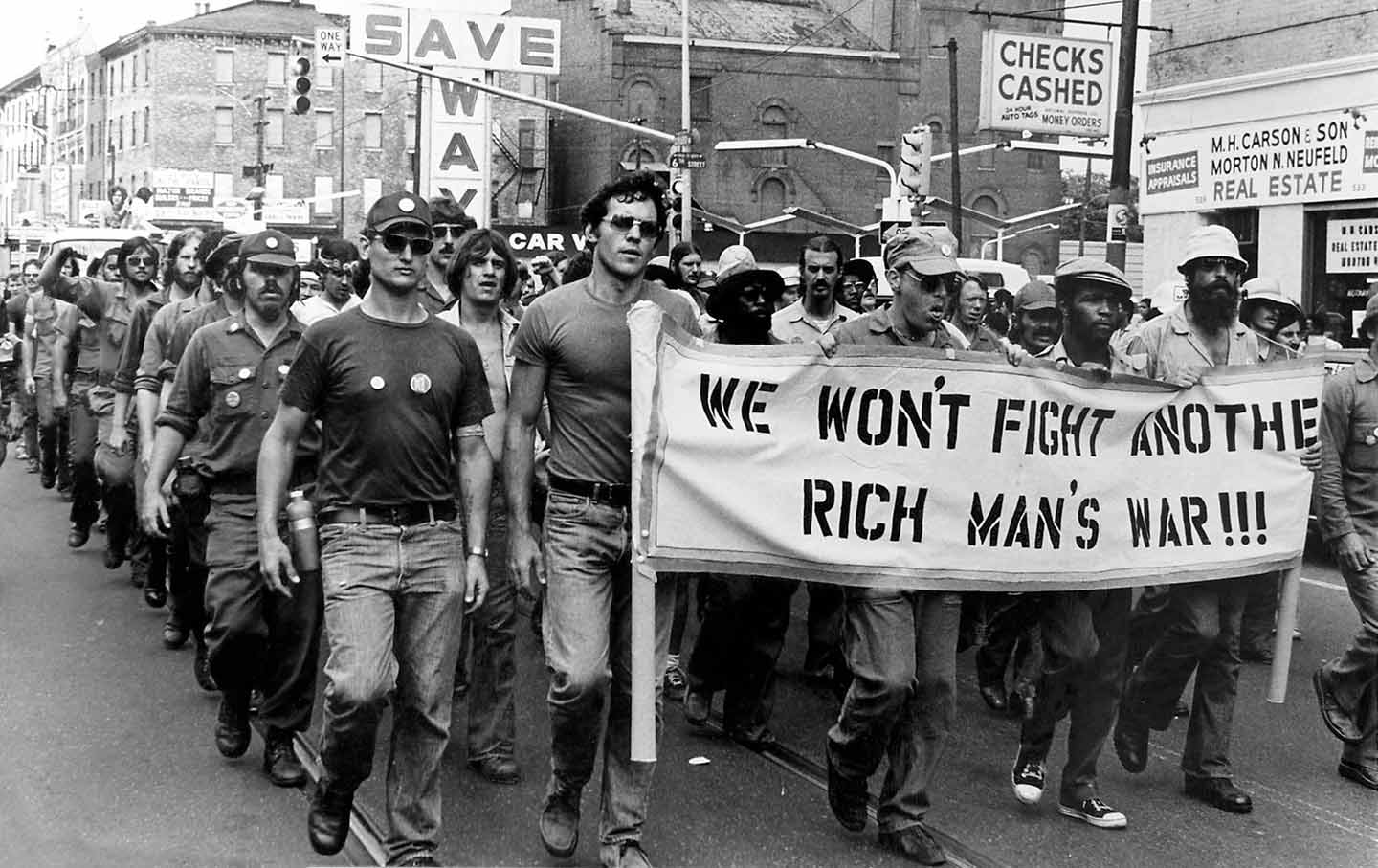

“WE WON’T FIGHT ANOTHER RICH MAN’S WAR”—an anti–Vietnam War protest in the 1970s. (Public Domain, via Zinn Education Project)

When Representative Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) speaks of the need for “a president who will fight against Western imperialism and fight for a just world,” she is crudely dismissed by her right-wing critics as “clueless.” When Representatives Mark Pocan (D-Wis.) and Barbara Lee (D-Calif.) call for making deep cuts in the Pentagon budget so that resources are not squandered on military interventions abroad, they are described as “admittedly extreme.” When Representative Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) speaks of breaking from “the colonial model of the world,” and of the vital importance of “prioritizing human rights,” he is portrayed as an idealist who is perhaps pushing the limits of the debate about foreign policy.

But these members of Congress, and others like them in an emerging generation of progressive leaders, are not expounding some new and radical faith that is delinked from US history.

Rather, they are reconnecting with the long-neglected and often-abandoned ideals that once animated honorable—if often lonely—advocates of the highest and best goals of the American experiment.

Two hundred years ago, on July 4, 1821, the nation’s eighth secretary of state, John Quincy Adams, spoke to the US House of Representatives on the role that the United States should play in the world.

“Wherever the standard of freedom and Independence has been or shall be unfurled, there will her heart, her benedictions and her prayers, shall be,” Adams declared. “But she goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy.”

That statement remains the finest expression of the unique balance that a republic must strike if it wishes to avoid paying the morally and politically unaffordable wages of empire.

In his address Adams reminded Americans that, while they have a responsibility to speak up for global democracy clearly and without apology, they have an equal responsibility to avoid entangling themselves in the turmoil of other lands. The most well-traveled and engaged American diplomat of his time, Adams was no isolationist. Yet he warned that these entanglements would ultimately undermine liberty in the United States—as they would require of America economic and political compromises that were inconsistent with domestic democracy.

“The fundamental maxims of her policy would insensibly change from liberty to force,” he said. “The frontlet upon her brows would no longer beam with the ineffable splendor of freedom and independence; but in its stead would soon be substituted an imperial diadem, flashing in false and tarnished luster the murky radiance of dominion and power. She might become the dictatress of the world: she would be no longer the ruler of her own spirit.”

This worldview, which inspired the organizers of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, has had a profound influence on Khanna, who says, “The United States foreign policy should be about exporting science, technology, and innovation—not endless, unconstitutional wars and weapons to regimes that don’t respect human rights. We need to return to the ideals of John Quincy Adams: Restraint in foreign policy.”

Yet Adams is a frequently forgotten figure in an American history that is almost always told too narrowly—and that the critics of Critical Race Theory would now like to tell even more narrowly.

When he is remembered at all, Adams is usually recalled as the one-term president who opposed the excesses of Andrew Jackson and who, after a turbulent tenure in the Oval Office, returned to the Congress. There, he fought to repeal the rule that prevented debate about slavery on the House floor; and eventually, as “Old Man Eloquent,” appeared before the Supreme Court to plead the case for freeing kidnapped Africans in the Amistad trial.

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

But it was as a diplomat that Adams was best known before his election as president. And his July 4, 1821, address to the Congress as President James Monroe’s secretary of state provided Adams with an opportunity to outline an anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist worldview.

After reading aloud from the Declaration of Independence—a document signed by his still-living father, John Adams, and authored by his father’s former rival Thomas Jefferson, who was also still alive—John Quincy Adams used his address to frame a vision of the United States as a country that rejected a career of empire.

“[America’s] glory is not dominion, but liberty,” he announced. “Her march is the march of the mind. She has a spear and a shield: but the motto upon her shield is, Freedom, Independence, Peace. This has been her Declaration: this has been, as far as her necessary intercourse with the rest of mankind would permit, her practice.”

In the critical passage of his address, Adams said of America: “Wherever the standard of freedom and independence has been or shall be unfurled, there will her heart, her benedictions and her prayers be. But she goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own. She will recommend the general cause, by the countenance of her voice, and the benignant sympathy of her example. [But] she well knows that by once enlisting under other banners than her own, were they even the banners of foreign independence, she would involve herself, beyond the power of extrication, in all the wars of interest and intrigue, of individual avarice, envy, and ambition, which assume the colors and usurp the standard of freedom.”

The genius of the American experiment, said Adams, was found in the revolutionary spirit of 1776, which rejected the corruptions of empire—the worst of which stem from the impulse to meddle in the affairs of other countries.

Adams concluded his address by urging Americans to renew their acquaintance with the revolutionaries against colonial meddling and empire who founded the American experiment, to celebrate their example, and to “Go thou and do likewise!”

Too few America leaders have followed this wise counsel. But there is an emerging class of leaders who recognize that, as Khanna says, “Adam[s]’s wisdom still applies as we seek to lead in the 21st century.”

John NicholsTwitterJohn Nichols is a national affairs correspondent for The Nation. He has written, cowritten, or edited over a dozen books on topics ranging from histories of American socialism and the Democratic Party to analyses of US and global media systems. His latest, cowritten with Senator Bernie Sanders, is the New York Times bestseller It's OK to Be Angry About Capitalism.