Vance could have been a key player in addressing the roots of the opioid crisis. Instead, he went in another direction.

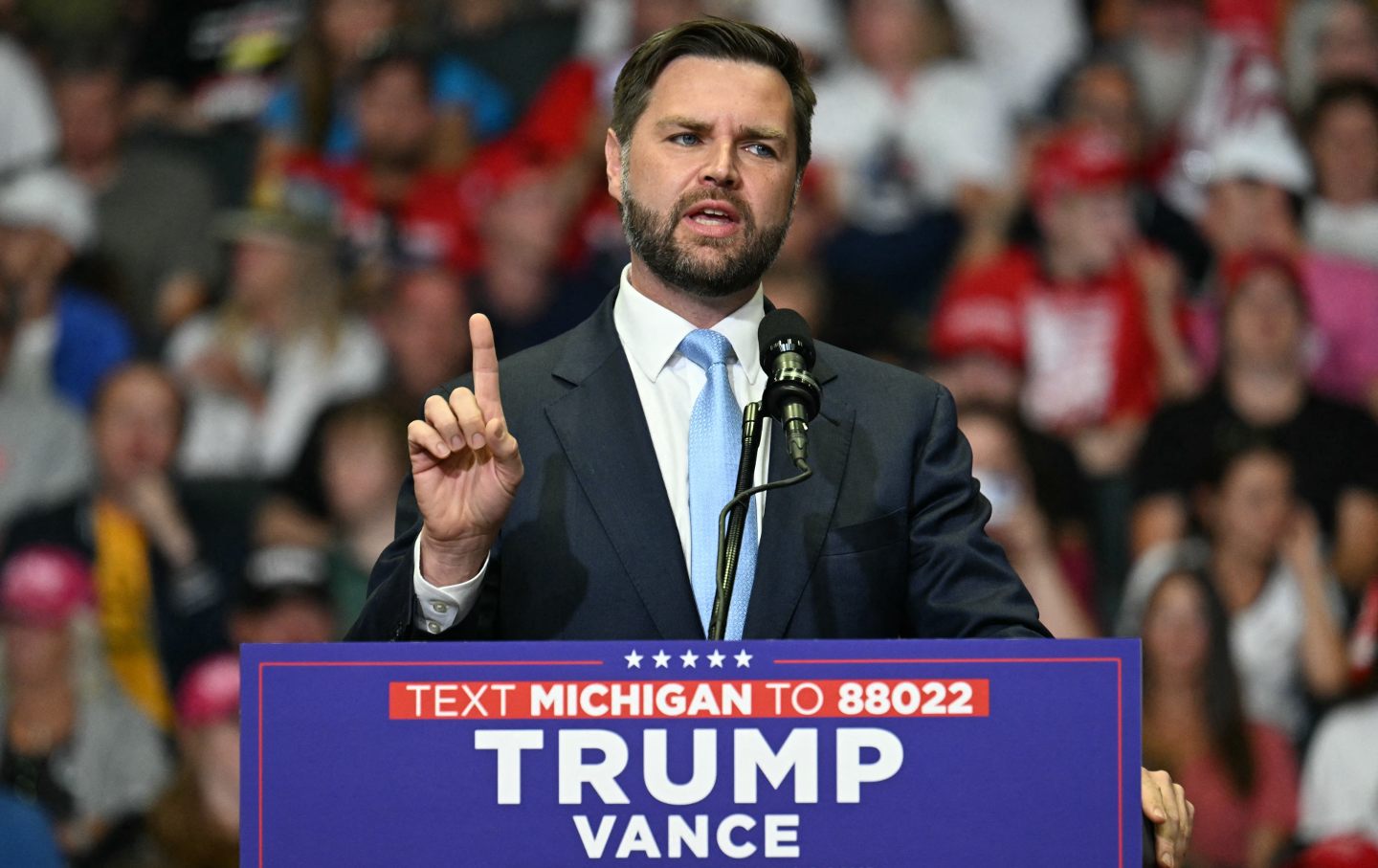

Republican vice presidential nominee Senator J.D. Vance speaks at a campaign rally in Van Andel Arena in Grand Rapids, Michigan, on July 20, 2024.(Jim Watson / AFP via Getty Images)

When I am not writing for The Nation, I have a day job researching substance use and infectious diseases. Every day, I am confronted with the weight of a set of interlocking national tragedies. For instance, the overdose crisis, which takes a life nearly every five minutes in the United States. But that crisis is also connected to infections, to diseases like HIV, to various forms of hepatitis, and to bacterial invasions of the inner lining of the heart’s chambers and valves—all of which take more lives, leave more families in grief, and cost our nation billions of dollars in lost productivity. This converging public health crisis is deadly serious. Some of the hardest-hit states in the nation are the poorest in the country—West Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky—in a region that is popularly known as Appalachia.

Last week, Ohio Senator J.D. Vance was selected as the Republican vice presidential nominee for the 2024 election. Of course, many people know that Vance came to fame in the memoir Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis, which he wrote about his upbringing in the midst of addiction. The book has been heralded by many and criticized by others.

I am not here to offer a book review. I am here to mourn missed opportunities.

The opioid crisis unites America in tragedy. Yes, Appalachia is hard hit, but so are urban communities all over the country. And so much of the prelude to the current moment has been driven by the history of race and drugs in the United States. As Helena Hansen, Jules Netherland, and David Herzberg have written in their book Whiteout: How Racial Capitalism Changed the Color of Opioids in America (and in the pages of this magazine), the crisis came out of a “breach of an implicit promise to uphold a safe, affluent white zone of clinical narcotic consumption, segregated from illegalized and hazardous racially ‘other’ street markets,” where instead of arresting young, white people, authorities went after the supply of prescription drugs, driving these same white users towards heroin and then synthetic opioids.

In Hansen, Netherland, and Herzberg’s analysis, the fates of white, Black and brown communities are inextricably linked together even if it is people of color who will always bear the brunt of punitive policies, left behind in access to care and prevention services. I urge you to read their book.

This could have been a moment, then, where we realized that unless we face the racial logic of American drug policy head-on, the lives of all people who use drugs will remain in jeopardy. And this is where we get back to J.D. Vance.

After the 2016 presidential election, Vance returned to his home state to start a charity called Our Ohio Renewal, in part to confront Ohio’s opioid epidemic. Imagine this Yale Law School grad, celebrated author, flush with cash from his stint in Silicon Valley, investing locally in the fight against this public health crisis. A man with these kinds of connections and resources—one whose own life was shaped by addiction—could do a whole lot of good. And Ohio’s opioid epidemic, as he would have learned, was not just about its Appalachian counties but its cities, and its impact on communities of color was growing to overtake that among white Ohioans.

But this wasn’t to be. Our Ohio Renewal turned out to be a sham, as covered by Business Insider, The New York Times, and The Columbus Dispatch among others. It raised little money and spent most of it on payments to Vance’s political consultant. The cynicism of Vance’s not-for-profit foray isn’t especially noteworthy. But still, it’s a kick in the teeth to those dealing with addiction in his state, as he wraps himself in the mantle of being their champion. Perhaps this kind of betrayal was also to be expected; as Gabriel Winant, a historian at the University of Chicago has written in n+1, Vance doesn’t see the crisis in Appalachia as one of systemic causes that have weighed the region down. Instead, he sees the failures in the poor themselves, starting with his own mother. (Winant’s essay needs to be read and reread for the most astute psychological and political profile of a man who would be king.)

But back to the plight of people who use drugs. Whither US drug policy under Trump and Vance? One could easily see the opioid crisis coming under the vice-president’s portfolio should he be elected in November and the narrative of personal weakness to be overcome, as described by Winant, being central to what comes next in the US:

Whatever else changes in his public commitments, the ethic of culpability persists. He represents the poisonous idea that the very real traumas suffered by the American working class over the past two generations are without structural cause and therefore can be overcome by willpower and self-discipline; that those who fail to do so have themselves, or otherwise malicious phantasms, to blame.

Add this to the general antipathy towards sensible substance use policy among politicians in both parties and I shudder at the possibilities for things to get worse.

Yet, despite all this I think there is room for hope.

At the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, my colleague Forrest Crawford and I wrote a piece suggesting that putting then–Vice President Mike Pence in charge of the response to this new disease was a mistake given his disastrous response to the outbreak of HIV among people who use drugs in Indiana in 2014. That 2014–15 response was coordinated by then-Governor Pence’s health commissioner Jerome Adams, who became surgeon general under President Trump. Since his departure from the administration, Dr. Adams has displayed a new independence from his party on drug policy—coming to the defense of needle exchange programs across the country. We’ve even written together on the subject. Sensible drug policy need not be a partisan issue. There are other roads to take in the face of so much suffering, sickness and death.

I can and do surely mourn the missed opportunities for addressing one of our gravest national crises, but we can organize for something better, even when, in fact, particularly when, things look the bleakest.

Gregg GonsalvesTwitterNation public health correspondent Gregg Gonsalves is the codirector of the Global Health Justice Partnership and an associate professor of epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health.