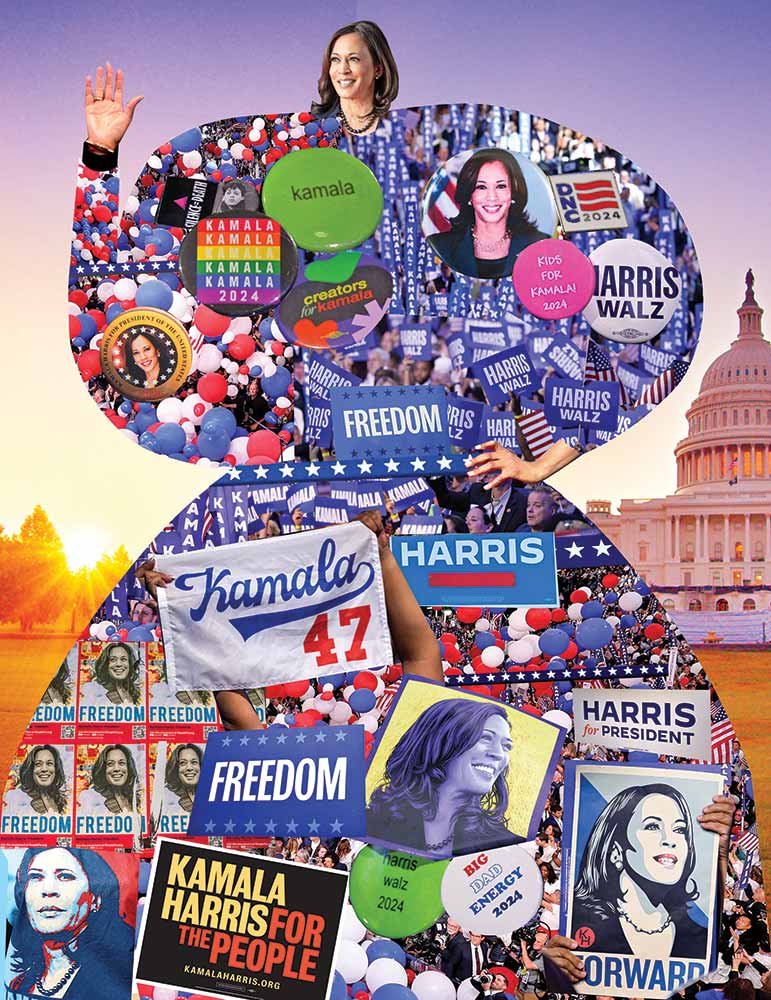

Can Kamala Harris “Win It All”?

The Democrats could win control of Congress and the White House—if they run a truly national campaign.

It was a few days after President Joe Biden halted his 2024 reelection campaign and endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris as his replacement at the top of the Democratic ticket. On Main Street in Platteville, Wisconsin, the Grant County Democratic Party headquarters was abuzz with activity. Volunteers were assembling yard signs for US Senator Tammy Baldwin, whose tough race for a second term suddenly seemed easier now that the party’s embattled president had dropped his flagging reelection bid. There was talk of flipping western Wisconsin’s congressional seat back into the party column. Folks were delivering plates of food “to keep everyone’s energy up!” Someone brought a radio so the volunteers could listen to the anticipated announcement of Harris’s VP pick.

“It’s just so good now,” said Sue Leamy Kies, a retired high school English teacher who, like many Democrats in rural America, had spent much of the summer fretting about Biden’s chances of beating Trump in November. “The vibe is different. It feels like we can turn this corner of Wisconsin blue, win it for Kamala, win it for Tammy, win the congressional seat. Everything seems possible.”

That’s a pretty enthusiastic take on the political zeitgeist from a town of just under 12,000 that is far from the urban centers where Democrats usually win votes. Southwestern Wisconsin’s Grant County is a stretch of rural America where Democrats garnered only 41 percent of the presidential vote in 2016 and just 43 percent in 2020, where a historically Democratic US House seat flipped to the Republicans in 2022, and where all the local legislators and county officers are Republicans. Yet it wasn’t so long ago that Democrats dominated in Grant County.

Not much more than a decade has passed since counties up and down the Mississippi River backed a young Democratic presidential candidate named Barack Obama. In Grant County, Obama won 61 percent of the vote in 2008 and 56 percent in 2012; the county also backed Baldwin in her 2012 and 2018 Senate races, and it supported the reelection bids of Ron Kind, the Democrat who represented the county in Congress for 26 years. The last few years have been tough, Kies tells me, but, she adds, “there are a lot of Democrats here. We have to get their confidence back, so they believe they can win and so they’ll turn out on Election Day. I think Kamala Harris does that.”

Kies is not alone in this sentiment. Ben Wikler, the energetic chair of the Wisconsin Democratic Party, said, “There’s a real possibility, if everyone works their heart out every second until the polls close, that we flip the House, hold the Senate majority, and win the White House. When that happens, we have an opportunity to send President Harris the bill to restore Roe v. Wade and the voting rights laws that Americans are clamoring for. This is a history-shaping moment. That’s what people [should be] fighting for now. It’s not just stopping a disaster,” he continued, referring to the real possibility that Biden’s declining fortunes might have caused the Democrats to lose the Senate and perhaps even the House. “It’s also the sense that we might really be able to expand American freedom in the next year.”

While Republicans and even some Democrats dismiss that scenario as wishful thinking, I wanted to explore the prospect that the ticket of Harris and a Midwestern vice presidential nominee, Minnesota Governor Tim Walz, might win big this November—and consider what such an outcome might mean for Democrats in 2024 and beyond. So, in August, I embarked on a series of drives across regions of the country where Democrats once held their own, but where Republicans have been on the march over the past decade. In addition to western Wisconsin, I went to Iowa and Nebraska, to central and western Illinois, to Indiana, and to Kentucky in search of answers to the questions raised by the new dynamics of the 2024 election.

I wanted to talk to the volunteers who opened campaign offices on small town Main Streets, the union leaders working to mobilize their members, the party chairs based in swing states, and the policy wonks and issue advocates whose on-the-ground work has taught them that winning the presidency will never be enough to change the course of US politics. Might the energy of the Harris-Walz ticket—so much on display at the Democratic National Convention in August—transform the party and the nation’s political discourse for the better?

The issue I set out to explore goes beyond esoteric discussions about vote totals and party positioning. It speaks to the bigger question of whether, having faced down Trump and Trumpism, Democrats could govern in a way that might markedly improve the lives of working-class Americans—as Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society did in the last century.

To do that, Democrats must win the presidency with an even bigger popular vote and Electoral College margin than in 2020, increase their narrow hold on the Senate, flip control of the House, and make substantial progress in the fights for control of statehouses across the country. A tall order, to be sure, but an essential one for changing the politics of a country that can’t afford another two decades of directionless policies. For far too long, we’ve witnessed a pair of behemoth parties trading their grips on the White House and the Capitol, while corporate interests play the margins to their inevitable advantage, an indefensible foreign policy consensus prevents meaningful action to address even a genocide in Gaza, and a corrupt Supreme Court governs from the bench on issues as consequential as maternal healthcare and the bestowal of kingly powers to presidents.

When a political party builds the right sort of momentum, as the Democrats did under FDR in 1932, under LBJ in 1964, and under Obama in 2008, it can gain what is referred to as “trifecta control”—control of the presidency, the House, and the Senate. And if the president enjoys broad popular support, it becomes possible to make platform promises real and to heed the calls for change from marchers in the streets.

Grassroots activists and policy advocates know this.

“We need a trifecta. We really, really need a trifecta,” Ai-jen Poo told me. The Chicago-based president of the National Domestic Workers Alliance explained that the goals of this fall’s suddenly supercharged campaign must go beyond simply holding on to what Democrats already have. “We need the big win so that Kamala Harris has the power to do big things: secure our democracy and enact legislation that saves lives, that improves lives, and that proves government can make a difference.”

But is that possible in a country that is said to be irreparably divided, where we are told by pollsters that the red and blue states are locked into their voting patterns and that everything comes down to a handful of swing states—and, within those states, a handful of counties?

I started to ask people on the ground—in places where Democrats have been losing elections, but where they might start winning again—what might happen if a party that’s known for its caution decided to go big. What about a scenario in which Democrats were able not only to hold their majority in the Senate but to expand it? Could red Missouri, where populist Democrat Lucas Kunce is mounting a spirited challenge to Republican incumbent Josh Hawley, actually go blue? Or could states like Nebraska and Iowa and the rural regions of Wisconsin and Minnesota elect Democrats to the House as they did in the none-too-distant past? Wins in those places, in combination with expected Democratic advances in California and New York, could restore a robust Democratic majority in the House and make bold governance possible.

What I heard was a mix of “Dare we dream?” enthusiasm tempered by knowing skepticism about whether Democratic Party leaders will recognize the full extent of the political earthquake that took place after Biden withdrew from the race.

“Everything changed when Harris took over as the nominee, and everything changed again when she picked Walz for her running mate. In, like, a day, Democrats went from saying ‘We’re fucked’ to saying ‘You know, maybe Trump is fucked,’” said Lori Wallach, who, long before she became the director of the Rethink Trade program at the American Economic Liberties Project, was a local television reporter and campaign aide in the upper Midwest. “The question now is whether the Democrats, who are really good at missing opportunities, will miss the chance to run a bigger race that might win it all.”

Democrats have a history of running well at the top of the ticket but failing to pull together governing coalitions. That happened to President Biden, whose first-term accomplishments were more impressive than those of his recent predecessors, but who fell far short of implementing his initial Build Back Better plan and advancing ambitious initiatives to reform policing, reduce carbon emissions on a timeline that addresses the climate crisis, and remove barriers to union organizing. It wasn’t that Biden didn’t want to do more; he couldn’t. During his first two years as president, the refusal of Democratic leaders to upend filibuster rules and the failure of Senate Democrats to unite around the boldest elements of his agenda led to compromises that prevented an increase in the minimum wage, the expansion of Medicare, and the extension of child tax credits. During the last two years of Biden’s term, the Republican majority in the House stalled agenda items that weren’t approved by Speaker Mike Johnson.

The 2024 race was shaping up as a repeat of 2020. Then Biden stood down.

The journalist and author David Sirota, who served as a senior strategist for Montana Democrat Brian Schweitzer’s unsuccessful Senate campaign in 2000 and his successful gubernatorial campaign in 2004, said that 2024 is ripe with opportunity and fraught with peril for Democrats: “With Trump, there’s a point where he could just run out of gas. If he starts to collapse, or just fall apart like Jimmy Carter in 1980, Democrats will have all the resources they need. There will be an overage. The question is: Where do you put the overage? Do you sit on your lead? Or do you use the resources you’ve got to expand the map in a way that wins more states for the presidential candidate and elects Senate and House candidates in what we are told are red states?”

The notion that Democrats might “expand the map” and “win it all” was unthinkable during much of 2024. Biden never fell so far behind Trump that he was certain to lose the presidency. But he never got so far ahead that he was certain to win, and it was hard to see where he could help Democrats win the House and Senate seats that would be needed to govern in a second Biden term.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →While the prospects for retaking the narrowly divided House were encouraging initially, setbacks in efforts to redraw district lines in key states had made the competition a close call. And the race for control of the Senate looked like a lost cause.

For the past two years, Democrats have maintained a tenuous 51–49 advantage in the Senate that has relied on a pair of uncooperative caucus members, West Virginia’s Joe Manchin and Arizona’s Kyrsten Sinema. But with Manchin and Sinema leaving, it looked like it could be tough for Democrats to hold their seats and the seats of several embattled incumbents who were seeking reelection. That’s because the 2024 election cycle comes six years after the 2018 cycle, when Democrats ran exceptionally well, boosted by a backlash against Trump’s presidency. In the Senate, they won previously Republican-held seats in Nevada and Arizona, and they held Democratic seats in the battleground states of Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania (all of which had backed Trump in 2016). Remarkably, they also reelected Jon Tester in Montana, Sherrod Brown in Ohio, and Manchin in West Virginia—states that gave Trump solid wins in 2016.

After Biden’s miserable performance in his June 27 debate with Trump, Democrats panicked. They feared that Trump could retake the White House while surfing a Republican wave that would hold the House for the GOP and give the Senate a pro-Trump majority.

As Harris transitioned with ease to the top of the ticket, Democrats nationwide breathed an immediate sigh of relief. “We love Joe Biden, hands down. But it was hard this year,” Nebraska Democrat Precious McKesson told me when we met at Johnny T’s, a bar on the north side of Omaha. In 2020, under her state’s distinctive system for distributing electoral votes, McKesson had cast a lonely Electoral College vote for Biden. “It’s not hard anymore,” she said with a huge smile. “With Kamala, the momentum has arrived.” As Harris started to tick upward in the polls and hold huge rallies in battleground states, it became clear that a seismic shift was taking place.

I asked Randi Weingarten, the president of the 1.8-million-member American Federation of Teachers, if the hype was real. Weingarten, who talked to me after Harris spoke at the AFT convention in Houston, said, “Oh, it’s real. Our members—urban, rural, East Coast, West Coast, in the middle of the country—are into this campaign. They’re into Kamala Harris. This goes way beyond battleground states. It’s everywhere!” A few days before Walz addressed the annual convention of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) in mid-August, I spoke with Lee Saunders, the president of the 1.4-million-member union. “Folks are really engaged,” Saunders said. “There is a level of excitement that I haven’t seen for a long time.”

In a coffee shop on the north side of Omaha, Jane Kleeb, the chair of the Nebraska Democratic Party, confirmed that impression. “We had to hire part-time workers in our Lincoln and Omaha offices just to handle the volume of calls,” she said. “Our regular staff couldn’t get anything done, because there were so many people calling from all over the state, asking, ‘When can I get a barn sign? When do we start doing doors?’ We’ve got young people coming into the office to volunteer. We have people literally knitting Kamala dolls. It really does feel like Obama in 2008.” A few weeks later, when Kleeb sat with the Nebraska delegation at the Democratic National Convention, she heard an echo of her assertion from former first lady Michelle Obama, who recalled the one-word theme of the 2008 Democratic campaign and linked it to the party’s 2024 campaign with the line “Hope is making a comeback.” And when former president Barack Obama appeared, chants of his old battle cry—“Yes, we can!”—rocked the convention.

But will it actually be anything like Obama in 2008? That year, the Democratic presidential ticket won 365–173 in the Electoral College, carrying states such as Ohio, Iowa, and Indiana, which pundits now imagine to be irretrievably Republican. Even in the states where Obama lost, the Democrats won enough Senate and House races to build the big majorities that passed the Affordable Care Act. Four years later, as Obama held on to Ohio and carried roughly two-fifths of the vote in Montana, North Dakota, and Indiana, Democrats won the Senate seats in those states. Democratic strength at the top of the ticket assured that the party would hold House seats in places like eastern Iowa and flip them in suburbs around the country.

So much has changed that it is probably unrealistic to imagine a renewal of Democratic fortunes parallel to 2008. The Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United ruling, along with a series of other judicial rulings that benefit big money, has mangled the financing of campaigns in ways that allow the billionaire class and its political front groups to flood the zone with unprecedented levels of spending. In 2024, that’s likely to help Republicans in Senate races whose winners will decide on the nominees who, in turn, will determine whether the Supreme Court remains in the service of corporate power. Sophisticated gerrymandering schemes have also crushed competition in much of America, while Trump’s tenure drove wedges of division into regions of the country where swing voters are now almost impossible to find.

These changes inject a measure of realism into all the talk of renewed hope. But they don’t overwhelm it.

Democrats don’t need an Obama-style victory to govern boldly. But they do need to maximize their numbers at the top of the ticket if they hope to govern effectively in 2025. Running a truly national campaign makes all the difference.

What might that look like? Start with Kamala Harris and Tim Walz touching down not only in states that they expect to win but also in some states that they’re unlikely to win. Then the party and its allies should distribute resources with an eye toward expanding the map of districts and states where Democrats can win House and Senate seats.

For the Democrats in Nebraska, that’s vital. The chair of the state party wants Harris and Walz to keep campaigning in Omaha to help secure an available electoral vote and the US House seat where the union-backed state legislator Tony Vargas is mounting a spirited challenge to the vulnerable Republican incumbent, Don Bacon. “There is so much more ground that Democrats can now potentially win,” Kleeb said. “There are so many downballot races that looked impossible. Now, if the Democrats make the right moves, it’s possible.”

In neighboring Iowa, where I saw people putting up homemade “Harris for President” signs in small towns like Newton, Harris and Walz will struggle to overturn voting patterns that gave Trump an eight-point win in 2020. But if adding a Minnesota neighbor with rural values does “energize [Democratic] voters across Iowa,” as Iowa State Senator Pam Jochum said in an August statement, the boosted turnout in the eastern part of the state and around Des Moines could allow the party to retake a pair of House seats formerly held by Democrats.

That’s the key to understanding Democratic prospects in 2024.

Of course, winning the White House is the top priority. But obtaining governing majorities on Capitol Hill will decide just how much that win matters.

To get those governing majorities, Democrats have to move beyond a narrow swing state strategy; they’ve got to boost Democratic turnout in red states. That’s critical for Democratic senators such as Tester in Montana and Brown in Ohio. It’s also critical for Democratic Senate candidates like Debbie Mucarsel-Powell in Florida, where the appeal of the Harris-Walz ticket and an abortion rights referendum could significantly increase progressive turnout, and for Colin Allred in Texas, where incumbent Republican Ted Cruz has very high disapproval ratings. And it’s especially true in Missouri, where a spike in Democratic turnout in St. Louis and Kansas City really could lift Lucas Kunce into serious competition with Josh Hawley.

That spike won’t come without a wide view of the 2024 race that avoids the mistakes the party has made in the past. Democrats in red states must be given the space to win on their own terms, said David Sirota. But a strong Democratic push at the top of the ticket, along with willingness to invest the party’s resources in red regions that might someday become purple, can make all the difference.

“The key is for the top of the ticket to get 45 percent—as opposed to 35 percent—in non-Democratic areas,” Sirota explained. “Then the local Democratic candidates do the rest.”

That’s something Democrats understand in places like Platteville. In western Wisconsin’s Third Congressional District, there was a contest in 2022 for an open seat that a Democrat had held for 26 years. National Democratic strategists wrote off the party’s nominee, imagining that the party couldn’t compete in rural regions. They underestimated the broad appeal of the pro-choice, pro-democracy, pro-labor message that state Senator Brad Pfaff was delivering. DC party strategists canceled television ads that were supposed to boost Pfaff, who was outspent four to one by his opponent. Yet on election night, Pfaff came agonizingly close to winning, grabbing 48 percent of the vote. “I firmly believe if there would have been greater resources…provided,” he told Wisconsin Public Radio after the election, “we would’ve won this race.”

This year, the prospects for winning the Third—and a lot of other districts like it—are real. Harris and Walz drew almost 12,000 people when they campaigned there on August 7. Democrats in Washington say there will be more resources for Rebecca Cooke, the party’s nominee this time. Kleeb, the Nebraska Democratic Party chair, says this is a moment for party leaders to recognize that there are suddenly more districts and states that could swing to the Democrats. “Kamala Harris and Tim Walz have an appeal that gives Democrats a chance to win in places that have been hard to win,” Kleeb said. “The national party has to recognize that possibility—and grab it!”

More from The Nation

How Democrats Can Fight Back How Democrats Can Fight Back

Jamie Raskin lays out the legal strategy to oppose Trump but says, “We’re not going to sue our way out of a political crisis”—Democrats need a political organizing strategy.

Donald Trump Is Stealing the Kennedy Brand Donald Trump Is Stealing the Kennedy Brand

Does the Kennedy name stand for liberalism—or oligarchy?

A Profoundly Un-American Moment A Profoundly Un-American Moment

Trump and his enablers have launched an unprecedented assault on American society and values.

Mitch McConnell’s Desperate Bid for an Honorable Political Legacy Mitch McConnell’s Desperate Bid for an Honorable Political Legacy

Lately McConnell has been a rare GOP vote against Trump’s worst cabinet nominees. But he’s the main reason Trump is back in power.