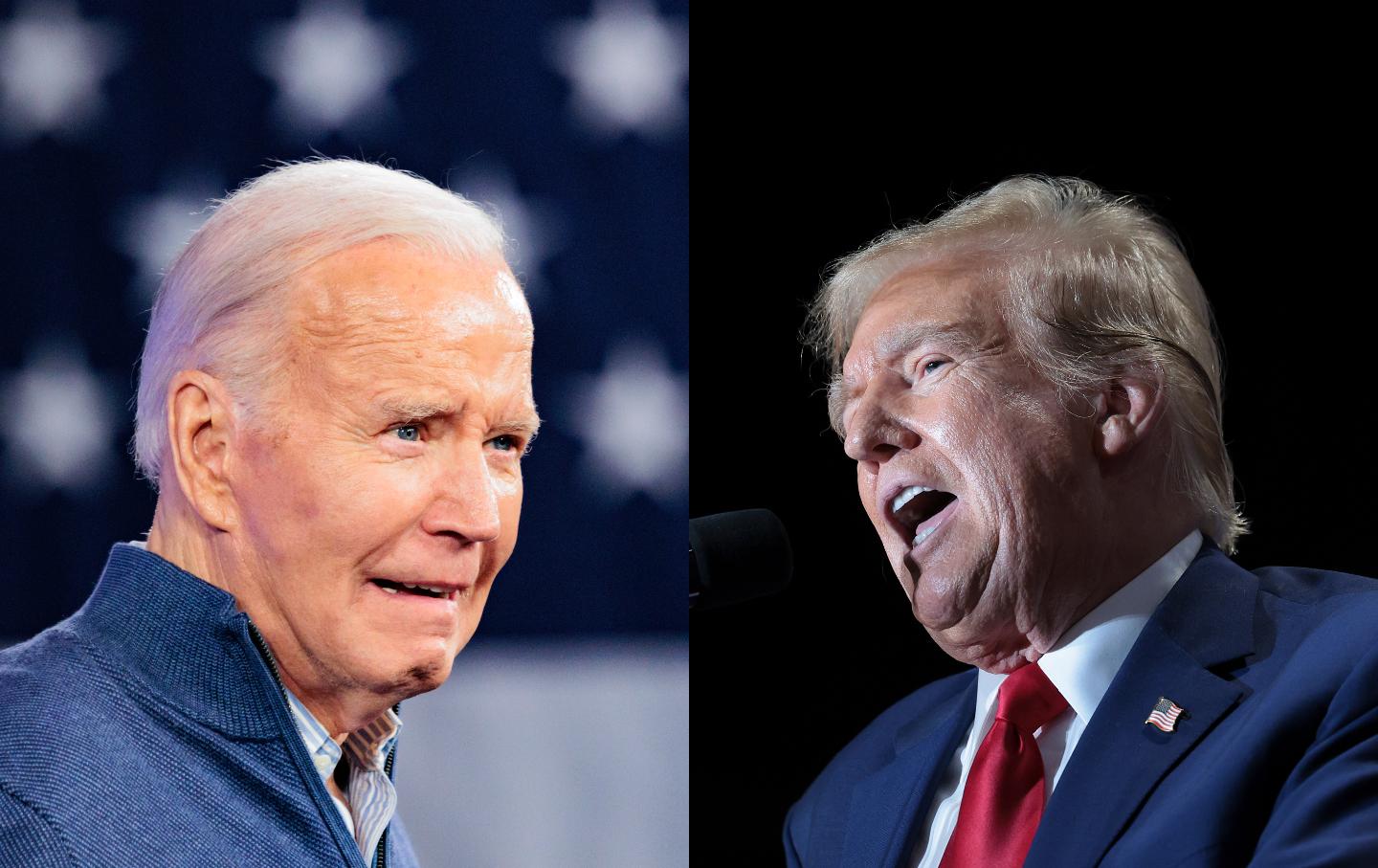

I won’t pretend that every South Park storyline has aged well, but the 2004 episode in which a Giant Douche and a Turd Sandwich ballot it out for school mascot is still spot-on when it comes to portraying the choices we’re typically given at election time. Twenty twenty-four finds us, yet again, with exactly the kind of lineup that South Park warned us about.

It’s no secret that Americans aren’t exactly excited about the prospect of another race between Joe Biden and Donald Trump. For the past year, polls have shown how little we want a rematch. In January, a Reuters/Ipsos poll showed that 67 percent of Americans in both parties were “tired of seeing the same candidates in the presidential election, and wanted someone new.” A recent Bloomberg poll found that the percentage of Americans who didn’t find one of the candidates either “dangerous” or “too old” is in the single digits; while Biden’s State of the Union address exceeded expectations, it’s unlikely to put the age question to bed forever. It’s not just polls, either; the steady presence of the “uncommitted” movement in primaries across the country shows the depth of dissatisfaction with Biden’s support for Israel’s bombardment of Gaza.

But all of this discontent can’t pull this flaming car over. We have our candidates, and one of them is deeply uninspiring, and the other one is Donald Trump. So, just like always, we are being exhorted to choose the “lesser of two evils” and hold our noses to keep Trump out of power.

If soaring rhetoric about democracy is the shiny surface of American politics, then “lesser of two evils” (or, as I’m dubbing it, LOTE) voting is the grubby underbelly—the bitter, toxic field on which the actual game is played. In theory, two qualified candidates have a dignified contest of ideas. In reality, someone is yelling at you on the website FKA Twitter about how America will die if you don’t vote for Joe Biden.

To an extent, LOTE voting is a consequence of a two-party system, which has existed in the US since its founding. “I think it’s inevitable that some of us (perhaps, often, many of us) will have to at least consider voting based on a ‘lesser of two evils’ rationale. Irrespective of whether or not we decide to vote in a way that’s guided by that rationale, the structure of the system forces us to contemplate it, even if only to ultimately have it outweighed by some other rationale/ideal,” says Dr. Robert Simpson, a professor of philosophy at University College London. It’s also a reaction to the choices we’re given within that system. Not to state the obvious, but believing you should be the one to lead the entire country is a negative personality trait. The primary process—which didn’t develop fully until the 1970s—gives voters some control over the nominees, but that doesn’t change the fact that, by and large, we get a small number of (likely) egomaniacal and unpalatable options.

I have no doubts that from the first time Americans voted, at least one person thought both the choices were bad (I would have loved to read lefty Twitter in 1796), but has it always been this bad? Has the idea that voting is just a choice between the LOTE always been the norm in American presidential elections? In many ways, yes, but the exact history is not only fascinating but also tells us something about this particular election.

The LOTE principle dates back at least as far as Aristotle, who wrote in Nicomachean Ethics: “For the lesser evil can be seen in comparison with the greater evil as a good, since this lesser evil is preferable to the greater one, and whatever preferable is good.” (Aristotle was a fan, it seems, but I’m pretty sure he never had to watch Trump and Biden face off twice.) LOTE voting has been around since the founding fathers, but, according to Jon Grinspan, curator of political history at the National Museum of American History, it really became notable about 60 years into our Republic. “The 1830s and 1840s are the period when we get a really strong two-party system, which supercharges the lesser of two evils thinking,” Grinspan says. “After the 1830s, the concept of two parties at war with each other puts a rigid scaffolding around ‘lesser of two evils’ logic for an individual candidate.”

LOTE voting is a mark of cultural dissatisfaction. For that reason, the 1840s and ’50s were big times for nose-holding, given that Americans were so divided that they would soon go to war with each other. It wasn’t just the parties that changed, though, according to historians. “Both parties fielded supremely unmemorable candidates, and the elections focused on who would do less harm,” says Dr. Lindsay Chernivsky, presidential historian and author of Making the Presidency: John Adams and the Precedents that Forged the Republic, describing the elections of the 1840s and ’50s. “While they didn’t necessarily use the language ‘lesser of two evils,’ many Northerners focused on who would either limit the spread of the evils of slavery, while Southerners looked for candidates that would not interfere in slavery, often using rhetoric about the evils of government interference.” (Some people, though, did use the LOTE language. Here’s Charles Sumner on the election in 1848, before he became a Radical Republican senator: “I hear the old saw that ‘we must take the least of two evils’…for myself, if two evils are presented to me, I will take neither.”)

These trends came to a head in the election of 1860. As Grinspan says, “It’s ironic, as he’s considered one of the best presidents in US history, but Abraham Lincoln was quite unpopular when he was elected. He was heavily criticized for being both not enough of an abolitionist and too much of an abolitionist; he won less than 40 percent of the vote in a four-way race. Still, enough voters did not want secession that Lincoln became the nose-holding choice for a qualifying number of voters.”

If the threat of secession pushed Lincoln across the line, then it was the threat of the losing candidates in 1884 and 1896 that compelled voters to hold their noses all the way to the polls.

In 1884, Democrat Grover Cleveland faced off against Republican James Blaine. Cleveland became embroiled in a sex scandal (he was accused of having a secret child out of wedlock—with a widow, no less) and Blaine was hit with allegations of financial corruption. According to Grinspan, the election was ultimately decided by a small number of New York voters who had to choose between these two improprieties, which in 2024 feels like a brag—OK, we get it, neither of your candidates had both.

In 1896, an election often compared to 2016’s, the country was in a financial depression and dissatisfied with its choices, but Democrat William Jennings Bryan was made out to be so radical that he threatened American democracy, so voters settled for Republican William McKinley. LOTE voting was encouraged in both elections, as evidenced by this 1884 report from The New York Times about a pastor who attacked both candidates but urged his congregation to vote for Cleveland (emphasis mine):

He denounced Blaine in the sharpest and severest language for the prostitution of his official position for corrupt purposes. He told the congregation that on the maintenance of honesty in public places and in high stations depended the salvation of the government.

To vote for a man convicted by his own testimony and by letters over his own signature as being corrupt was, the preacher said, beyond his comprehension. He also reviewed Blaine’s religious life and particularly denounced his renunciation of the Catholic religion. He then referred to the Democratic candidate, Grover Cleveland. As Mayor of Buffalo and Governor of the State of New York, he had shown himself to be the very embodiment of honesty, which was so earnestly desired in our public men. A man, he said, who had so successfully and honestly administered the affairs of a great state was the proper person to elect to the presidency of the United States.

He referred to the published scandal in reference to Cleveland, and in nowise mitigated the odium which should attach to it. He, however, advised the congregation to choose the lesser of two evils. Cleveland would secure an honest administration of the affairs of the nation, while Blaine was self convicted of corruption in high stations.

There are at least three alternatives to LOTE voting: A voter can abstain, find a third option, or (and I know this sounds weird) genuinely like one of the two candidates. The first two are similar—they’re a stand against one of the major parties. History has some lessons on when and which type of voters feel more comfortable risking it with a third party or abstention, and when they resort to the LOTE.

“Historically, a majority of African Americans voted the Republican ticket in the late 19th century, even after the Republican abandonment of Reconstruction, as the ‘lesser of two evils’ compared to the Democratic Party, which was then the party of the Jim Crow South,” says Dr. Manisha Sinha, Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut.

It stands to reason that a person who’s at risk of losing their rights is more likely to vote out of fear, rather than out of enthusiasm, which is when LOTE voting is most common. This lines up with what we’ve seen at the ballot box since Roe v Wade was overturned: Voters who haven’t otherwise participated in non-presidential elections have come out to protect their rights.

There’s limited data on the racial demographics of third-party voters, but some surveys do suggest that it’s more common among white voters, who are—despite what Chris Rufo will tell you—always at a lower risk of losing rights. Third-party voting and abstentionism also flare up when the economy is humming. “In good economic times, like the 1920s and the 1990s, partisanship is way weaker, as is turnout, and so it’s easier to feel safe taking a risk on someone outside of the two-party system,” says Grinspan, who added that this isn’t a hard-and-fast rule: The election of 1860 came at a precarious time in American history and still featured four parties.

That’s not to say third-party voting or abstention is only for the privileged; there are other times when neither party is offering enough on a key issue for the vote to even be worth it. But historically, we’ve seen LOTE voting in times of fear, not satisfaction.

There are also times when LOTE voting and third-party voting happen in conjunction, as they have the same cause. “I think the ‘lesser of two evils’ concept is a product of weak parties,” says Chervinsky. “Weak parties produce intense partisanship because they cannot control their members and protect officials who have different opinions. As a result, moderate positions and compromise are more difficult because moderates are attacked as ‘squishy’ or ‘weak.’ In order to shore up support, weak parties have to point to the other side as dangerous.”

In Naomi Klein’s book Doppelganger, she writes of how the doppelgânger emerges throughout history and literature to warn us that something is amiss. In this sense, a popular third-party candidate is a doppelgânger of both major parties: a person whose support reflects the failures of the front-runners. The relationship between the two is tricky to understand, because, as Grinspan says, “third-party voting is measurable, and LOTE voting is not.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The historians pointed out a few elections with strong third-party candidates. Nineteen twelve, 1924, and 2000 all featured robust third-party challengers and a deeply dissatisfied electorate. “All three come at times of historically low turnout—1924 is the lowest since popular voting began—which is a useful indicator that something’s not connecting with most voters,” says Grinspan. In 1924, the Progressive Party candidate Robert La Follette had made a career of fighting corporate and political dishonesty, which made him an ideal choice for those tired of DC corruption. In 2000, the Green Party’s Ralph Nader didn’t earn any electoral votes, but he did have an influential role because of how close the election was.

Perhaps the third-party-dominated election with the most to teach us about 2024 is 1968. It’s been cited many times in recent weeks as evidence that it’s not too late for Biden to step down: In 1968, incumbent Lyndon B Johnson opted out of the race at the end of March. The general election became a race between Johnson’s vice president, Hubert Humphrey, and Richard Nixon, who pitched himself as the anti-establishment candidate. “Democrats weren’t going to vote for the Republican, but their party broke the system with Vietnam,” says Zelizer. In a similar way that younger, left-leaning voters are growing more disenchanted by Biden’s support for Israel, these voters turned against Humphrey because of his support for the war in Vietnam (though there are some differences—Humphrey was not an incumbent, for example, and American soldiers aren’t fighting in Gaza). The other huge factor was the candidacy of arch-segregationist George Wallace, who took millions of votes from Humphrey. (The most prominent third-party candidate in 2024, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., is a buffoonish anti-vax conspiracy theorist, and it remains to be seen how many votes he gets.)

The third alternative to LOTE voting is the most basic—an election in which voters are excited by their choices, or overwhelmingly in favor of one. As Zelizer explains, “The opposite of a lesser of two evils election is a landslide. Take 1964 —Lyndon Johnson was seen as a traditional Democrat, while Barry Goldwater was considered an extreme figure.” According to Zelizer, the same was true in 1980, with the parties reversed—a charismatic Ronald Reagan defeated incumbent Jimmy Carter (widely perceived as weak) by about 10 points. Multiple historians I spoke to cited FDR’s popularity in the 1932 and 1936 elections, as well as Barack Obama’s positive “hope and change” messages in the 2008 campaign.

So, has it always been this bad? Grinspan described our current moment as the worst of the 19th and 20th centuries—ultra-competitive, intensely personal, and with weak candidates. Perhaps it’s for that reason that it feels like there’s more pressure around LOTE voting than ever.

“The ‘lesser of two evils’ argument has become more common on the left because of the rightward drift of the Republican Party, which has become worse in recent years,” says Sinha. “With many Republicans unwilling to denounce Trump’s authoritarianism, many people on the left, including myself, would rather vote Democratic despite our reservations about certain aspects of the Biden administration’s foreign policy.” Additionally, Biden’s advanced age makes him a worse candidate than he is a president: A voter can support the job he’s done and still not think he should be reelected.

But here’s perhaps the most relevant question of all: Does it matter? An enthusiastic vote counts the same as a fearful or defeated one. And although low voter turnout has been linked to dissatisfaction, 2020’s turnout was the highest we’ve seen since 1960. Fear and disgust are powerful motivators.

This is a contrarian opinion, but I’ve always been surprised by how many people vote. Almost 67 percent of eligible voters did so in 2020, even though only about a third of Americans live in swing states. An issue that’s endorsed by 67 percent of the country is wildly popular, which is to say, Americans are aligned on at least one thing: the importance of voting. Voting isn’t paid, and there’s no free childcare on Election Day. And yet, we vote. We vote no matter how busy we are or how pathetic our choices are. I haven’t been to the dentist in three years, and I’ve made the time to vote for Andrew Cuomo twice. Something’s not right.

I started digging into this because I thought analyzing the history might make me feel better. I did not find comfort—never making that mistake again! Almost every historian I spoke to noted that we’ve had a historically long string of nose-holding elections; the most comparable time in American history was the 1850s and ’60s, right before the Civil War. I intend to vote for Biden again, but I understand why people abstain or vote third-party. After all, the lesser of two evils is still evil.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

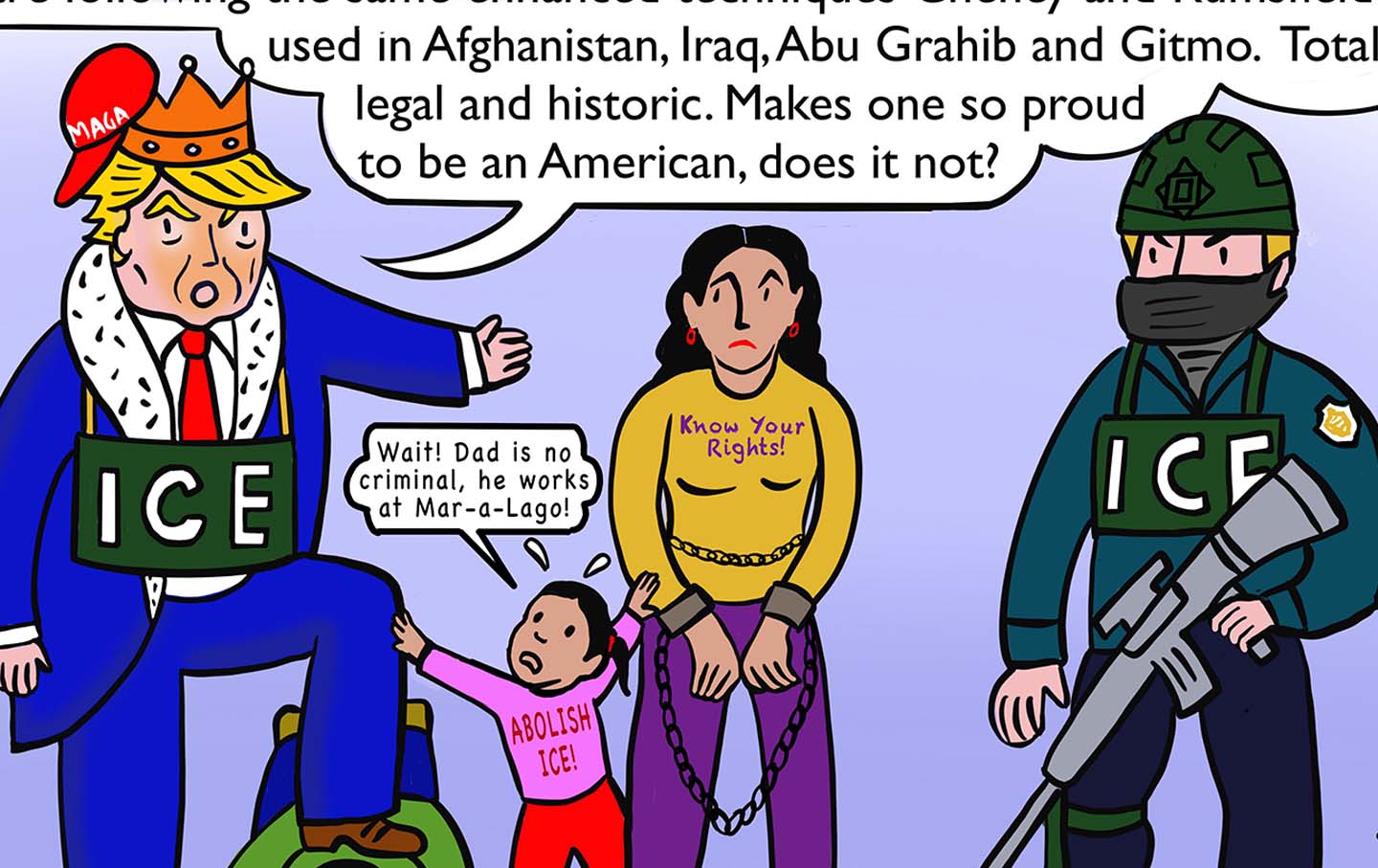

The King of Deportations The King of Deportations

ICE’s illegal tactics and extreme force put immigrants in danger.

How Rob Reiner Tipped the Balance Against Donald Trump How Rob Reiner Tipped the Balance Against Donald Trump

Trump’s crude disdain for the slain filmmaker was undoubtedly rooted in the fact that Reiner so ably used his talents to help dethrone him in 2020.

The Economy Is Flatlining—and So Is Trump The Economy Is Flatlining—and So Is Trump

The president’s usual tricks are no match for a weakening jobs market and persistent inflation.

Trump’s Vile Rob Reiner Comments Show How Much He Has Debased His Office Trump’s Vile Rob Reiner Comments Show How Much He Has Debased His Office

Every day, Trump is saying and doing things that would get most elementary school children suspended.