On the Front Lines of Florida’s Abortion Wars

With reproductive rights on the ballot, tensions are higher than ever in abortion-clinic parking lots.

On the Front Lines of Florida’s Abortion Wars

With reproductive rights on the ballot, tensions are higher than ever in abortion-clinic parking lots.

This story is part of States of Our Union, a series presented in collaboration between The Nation, Magnum Photos, and the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

This story was co-published with Le Temps.

For years, the same scene had played out outside the small Woman’s World Medical Center every Saturday and Monday, the clinic’s appointment days. The facility, which opened in 1991 more than an hour north of major urban centers on the Florida coast, is the last abortion provider in the area. And it cannot afford a permanent physician.

In the Florida heat, pro-lifers waited for the small black car that had left a few hours earlier from a medical center in Fort Pierce, a city of 47,000 on the Atlantic coast. There it was, at last. The driver had gone to pick up a doctor at an undisclosed location. The mysterious passenger wore a false beard and hat to avoid being recognized, a strategy justified by the murder of several abortionists in the United States since the 1990s. “Murderer! Butcher!” a pro-life activist shouted before the car disappeared into the narrow garage of the green mansion that houses the clinic.

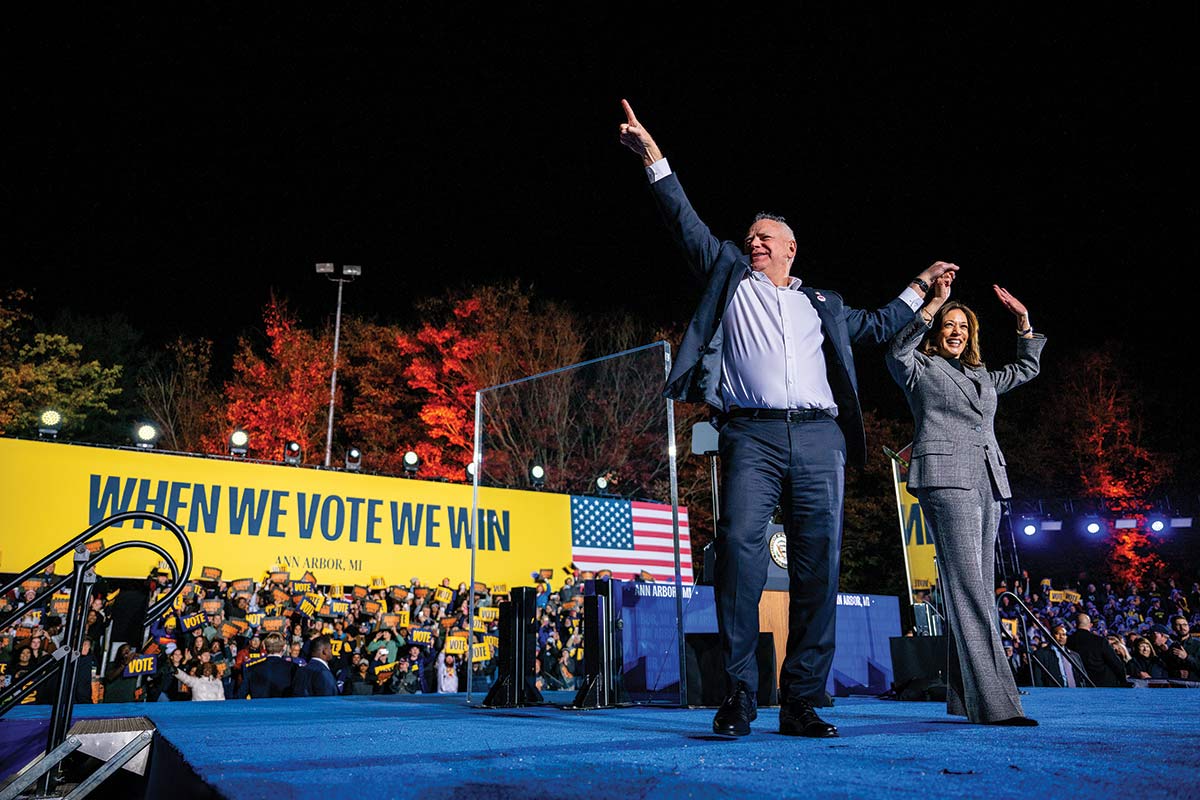

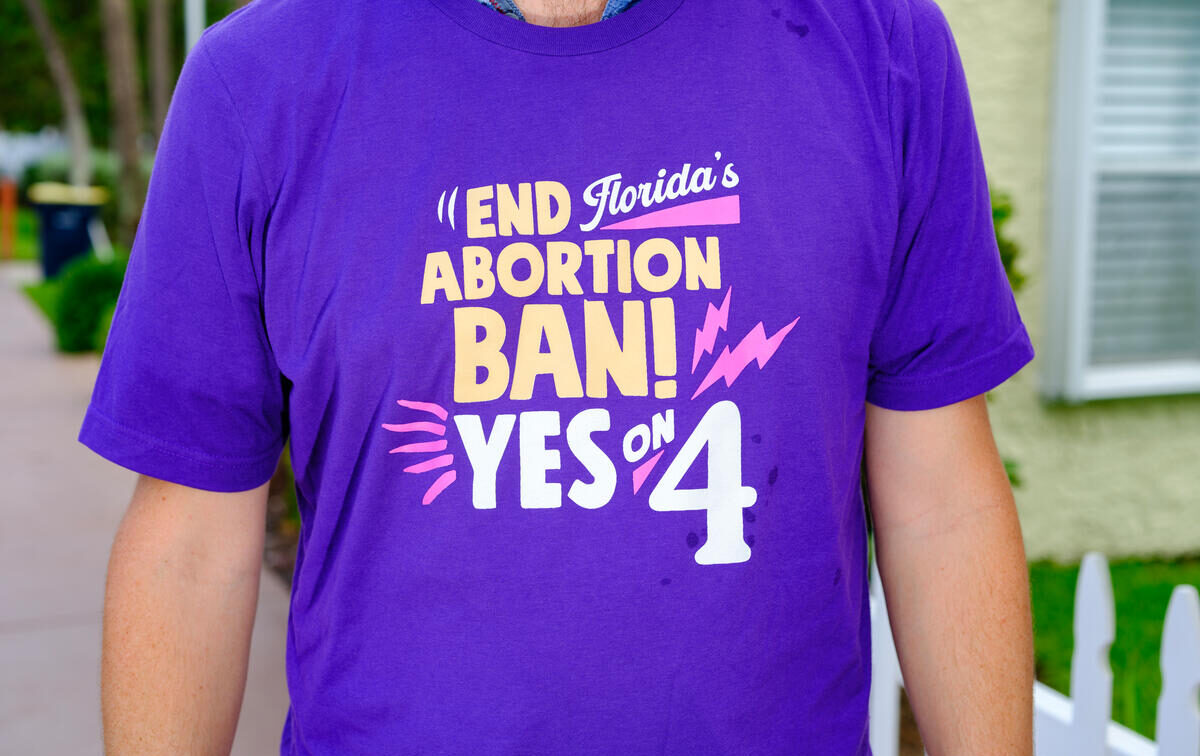

On May 1, Florida made abortion illegal after only six weeks of pregnancy, half the time allowed in Switzerland. At that early stage, many women do not even realize they are pregnant. But a coalition has gathered enough signatures to change the law, which was passed at the urging of Florida’s ultraconservative governor, Ron DeSantis. Amendment 4 aims to restore abortion rights up to 24 weeks and will be on the ballot on November 5, the same day Floridians will choose between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris. Nine other states will vote on the issue that same month. Since the Supreme Court struck down the federal right to abortion in June 2022, votes have systematically gone in favor of the defenders of free choice.

Since the new law went into effect, the clinic has seen half as many patients. Abortions in Florida dropped by more than 30 percent in May and June, according to early figures from the Guttmacher Institute, a research center specializing in reproductive health.

In 2023, more than 84,000 abortions were performed in Florida, and nearly 10 percent of those women came from other states. Today, Floridian women are forced to travel if they want to terminate their pregnancy after six weeks, with the nearest destination being North Carolina, about 621 miles away. But the state, where abortion is legal for up to 12 weeks, requires two consultations and a 72-hour waiting period, which increases the cost of a stay there.

When we rang the doorbell of the clinic, the driver who picked up the doctor carefully opened the door. His wife, who runs the center, could not see us until the next day, which was less busy than Monday. Three young African American women had been waiting for the doctor since the morning in the waiting room, which was too small to accommodate the patients’ families.

Behind a window in the medical center, a poster of Kamala Harris greeted visitors. The vice president has made defending women’s rights one of her campaign priorities, as Democrats hope that local votes on abortion will mobilize voters behind the vice president and swing Florida, which has been solidly Republican since the advent of Donald Trump.

In the clinic’s four-car parking lot, two retirees stood guard on folding chairs in the shade of a tree, wearing pink vests that read “Pro-Choice Escort Clinic.” “We have been coming every Monday for five years to escort women to the door and protect them from demonstrators,” said Pat Gaede, a local resident. A few feet away, pro-life activists faced them with placards showing fetuses or dramatizing the consequences of abortion.

Rosary in hand, Marc Richard, a devout Catholic and US Army veteran, walked around the clinic praying. He knew he was not allowed to cross the sidewalk to enter the clinic. “We’re not going to convince a woman by yelling at her,” he said to show his good faith. Next to him, Jim, who refused to give his full identity, waved flowers at a young woman who had just parked her car. Sometimes they accept these symbols of life. Then I take the opportunity to give them information about alternatives to abortion,” he said, his hands full of pamphlets. While one outlined the stages of fetal development and claimed that the heart begins to beat at 21 days, the other accused the pro-life organization Planned Parenthood of “racism” against African Americans.

On that Monday in September, the protesters did not reach their end. The first young woman to arrive in the afternoon rushed into the clinic, her ear glued to her cell phone so as not to hear their screams. She was followed by the two volunteers in pink vests. In the early afternoon, Karen Chappell, another volunteer escort, replaced the retired couple. She immediately planted pro–Amendment 4 signs to mark the clinic’s territory.

Over the years, the part-time nurse had come to know all the protesters. “I call the little Hispanic girl Mother Teresa, because she sprinkles holy water all over the place. The taller one calls me ‘devil bitch’ in Spanish,” she said, pointing to the two women pulling signs out of their car.

The new arrivals were louder than in the morning. “The worst is on Saturdays, Chappell added. Young men usually come from an evangelical church not far away. The clinic opens at 5 am, and the protesters arrive just as early. Sometimes the neighbors call the police because there are people shouting under the clinic windows,” added the slender woman in her 60s. “When I was young, my sister got pregnant, but she would not have been able to support the child. My parents supported her having an abortion, which was very progressive in the 1980s.”

A few other women entered the clinic, one with a young man who quickly left. As if it were a flea market, the Hispanic protester yelled at them, “Shelter, adoption! Everything is free!” With long strides, the activist chased after the car of a patient who had quickly closed the door, her eyes buried under a cap. When approached, the activist angrily told us to talk to her husband. The man, his head bowed toward the clinic’s windows, held up a loudspeaker and recited passages from the Bible. Freddy Castillo, a Venezuelan immigrant who arrived in the 1980s, loathed women who “spread their legs without taking responsibility for the consequences,” he said. “Since I’ve been here, I’ve managed to stop two women from having abortions. I’ve saved two lives, which is priceless, but since they’ve started being escorted, we can no longer talk to them,” Castillo added.

As he grumbled, a young blond girl stepped out into the parking lot. She looked anxiously around for the car that would pick her up and take her home. The shouts of the demonstrators doubled. “This is insane,” she said. “As if having an abortion is easy.”