A conversation with the first woman speaker of the House about battling Republican extremists and making it possible for Democratic presidents to achieve epic victories.

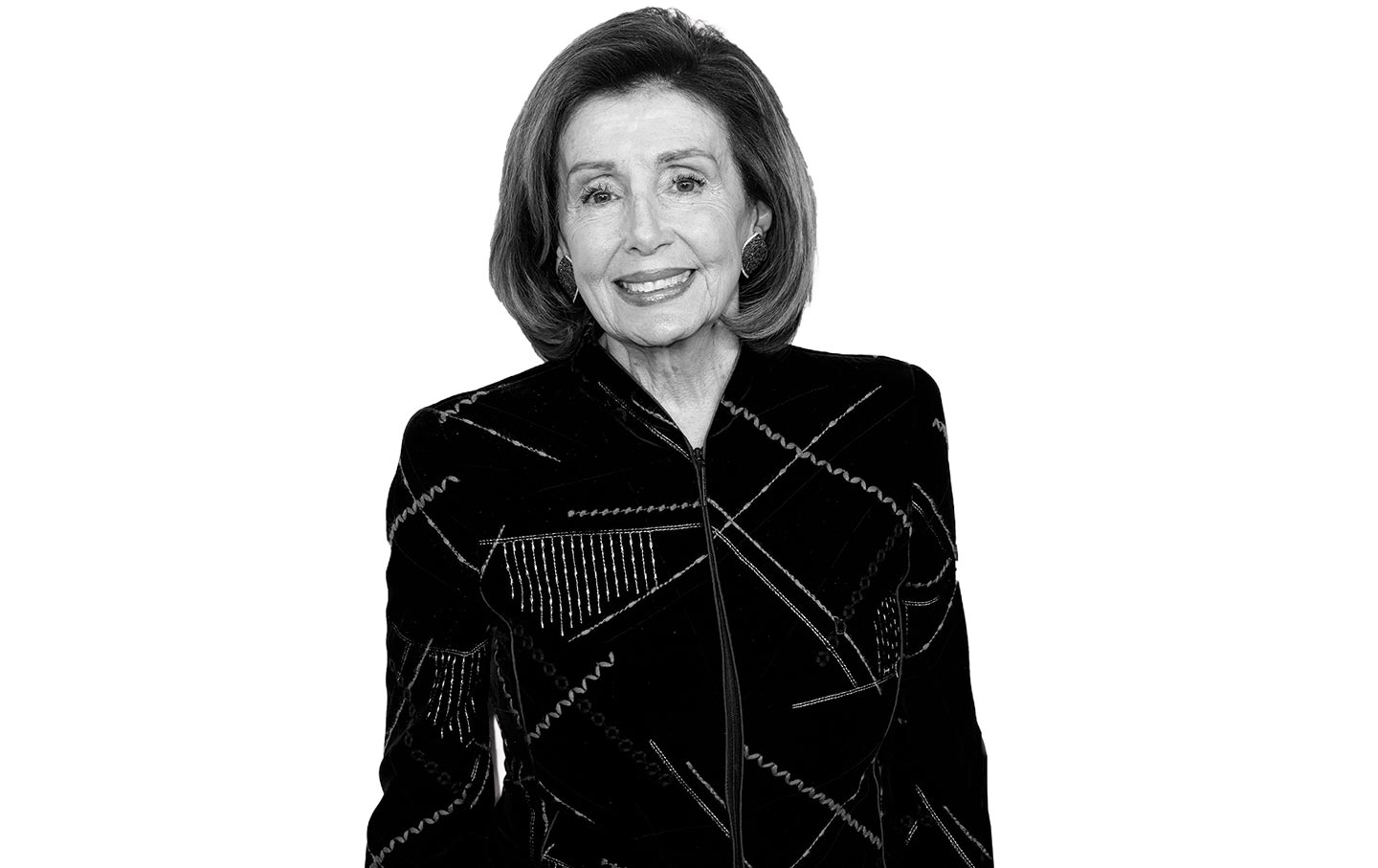

Nancy Pelosi, according to National Public Radio, is “arguably the most powerful woman in American political history.” The Urban League describes her as “the most successful and effective Speaker of the House in U.S. history.” The Associated Press employs no qualifiers, simply referring to the Democrat, who has represented San Francisco in the US House of Representatives since 1987, as the “dominant figure for the ages.”

Pelosi was a prime mover in the passage of the Affordable Care Act during Barack Obama’s presidency. She was the face of congressional opposition to former president Donald Trump. When Joe Biden defeated Trump in 2020, she united House Democrats to support the new president’s agenda. Even after handing off the leadership of the House Democratic Caucus to Hakeem Jeffries of New York, the “speaker emerita” remained so influential that she was widely seen as having nudged Biden to give up his reelection bid in a move that reenergized the party’s prospects by positioning a longtime Pelosi ally, Kamala Harris, as the Democratic standard-bearer.

In late September, when Pelosi sat down with The Nation for an exclusive interview to discuss her career and her best-selling book, The Art of Power: My Story as America’s First Woman Speaker of the House (Simon & Schuster), she remained coy about just how much of a role she had played in remaking the 2024 Democratic ticket. But she had plenty to say about battling Republican extremists—including Trump—and making it possible for Democratic presidents to achieve epic victories on Capitol Hill. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

—John Nichols

JN: For the better part of 20 years, Republicans have run against you—not against the Democratic Party, but against you personally. Why do you think that is?

NP: Because I am effective. I always say that if I were not an effective legislator, an effective fundraiser, effective politically, it wouldn’t matter to them.

JN: But it has mattered. And the attacks have often been strikingly crude.

NP: Unfortunately for my children, they saw that demonization, because [the Republicans] didn’t just say, ‘We disagree on this issue’ or not. That’s part of our democracy… to express that [disagreement]. But the cloven feet and the witch hair and the demonization was something that my kids think contributed to the attack on my husband [Paul Pelosi, who in 2022 was beaten by an intruder at their San Francisco home].

JN: Is it fair to say campaigning and governing have grown far crueler and more dangerous in the years since you were first elected to Congress?

NP: Well, what happened was that, in the 1990s, Newt Gingrich initiated the politics of personal destruction when he went after the Clintons. The people that were our friends across the aisle all of a sudden were calling us “treasonous” and “traitors” and all the rest—because that was [Gingrich’s] lingo that helped keep him in power, and that elected some of those people with the money he raised with that message.

So it’s very different, and it’s so sad, because to disagree is part of a democracy. We have different points of view. We do not have a monarchy. We have a beautiful diversity of opinions in our country. And the wonderful challenge of coming to Congress was to be able to debate your point of view, to listen to others, to understand the leverage you had to either win the day or to come out with a high split on it, and to recognize that tomorrow is another day, and there’ll be other fights to fight. So we were all a resource to each other on both sides of the aisle, and we didn’t want to weaken anybody. That’s what [changed] in the ’90s. But then it was exacerbated, of course, in the 2000s.

JN: Elections took on a win-at-any-cost character.

NP: Yes, it’s most unfortunate, because we want people to have confidence in government—to respect the differences of opinion that we have and how we debate them. But if all they know about government is what they see in campaigns, and they see what you just described, it’s very disconcerting to the public.

We are a democracy, and that confidence that the public has in the process is very important. That’s why we have to try to unify the country again.

Look, Donald Trump did not invent some of the negativism that is out there due to insecurities that some people have—being afraid of the progress of women and minorities and LGBTQ people and the rest of that. But he certainly exploited it, normalized it, and blew it up. He’s incompetent in every way when it comes to governance, but he is a capable snake oil salesman.

JN: When did you first realize that President Trump was going to be not just a difficult or a complicated opponent, but a dangerously dishonest opponent?

NP: We saw it in the very first meeting that we had with him—the meeting of the bipartisan leadership of the House and Senate with the president of the United States…. The meeting [began] with the president leaning on the table, with his arms on the table, and his first words…were, “You know, I won the popular vote.”

JN: When, in fact, he didn’t.

NP: I said, “No, you didn’t, Mr. President—that’s not true. You did not win the popular vote.” So that was our first meeting with the president, and that was so disappointing…. And then it was just one disappointment after another. As you know, [Republicans] had the majority at that time, and the only thing they did was pass a tax bill that [was projected to give] 83 percent of the benefits to the top 1 percent, adding 2 trillion—that’s trillion—dollars to the national debt. And then saying we couldn’t afford things like feeding the children and the rest.

JN: You have said that it “became clearer and clearer that his patriotism was in doubt.” But you still had to deal with him. When you ripped up the State of the Union address after he finished speaking in 2020, what was going through your head?

NP: Well, here’s the thing, I certainly had no intention when I went to that [joint session of Congress] to do that…. But on the first page, he was lying. So I just tore the page [to mark where the lies were], so I could go back to this page to see where he was lying. And then I realized he was lying on every page. Every page had a tear where he had lied. And it was so disrespectful of the Congress. It was horrible.

So that’s what was going through my mind. It was a manifesto of lies, and that’s why I tore it up.

JN: After Biden was elected, you were able to pass a great deal of legislation—even though the House Democratic majority was small. How did you hold the caucus together?

NP: We know why we’re there. We know whose purpose we were serving, and that is America’s working families…. So that’s why it was possible—not easy, but possible—to get these things done. And I’m a legislator; I love doing that. I just… I just love doing that.

JN: What’s been your proudest accomplishment as a member of Congress?

NP: There’s no question: It will be the Affordable Care Act—just springing from Martin Luther King Jr. saying, of all the inequality that is out there, the most [widespread] and inhuman is the inequality to [health]. For 100 years, presidents had tried to provide access to quality healthcare for Americans, for many more Americans, without success. We came in [in 2009, as a Congress with solid Democratic majorities and a Democratic president] with this as a priority, with it as an aspiration and a determination to get the job done…. The insurance companies ruled the roost. They called the shots on all that had happened before, and we changed the leverage to be for the people.

JN: San Francisco, your political base, has in the last quarter-century produced one woman leader after another: Dianne Feinstein, Barbara Boxer, yourself, and now Kamala Harris. What is it about San Francisco?

NP: We have respect for people. We’re not afraid of diversity…. We believe that women in politics is not a zero-sum game; if one person succeeds, it doesn’t mean “OK, that’s it, we have one woman.” It doesn’t mean that at all. It means every woman’s success is every woman’s success, and that just keeps opening doors to more success.

Kamala, I know her personally. She’s a person of great faith, deep faith, which is manifested in her love of community, her public service, her civic involvement from early on…. She’s politically astute. If she were not that, she would not be where she is today…. She’s wonderful. We’re so thrilled. I almost can get emotional talking about it.

But I’m glad she’s not running a campaign that says, [“Vote for me] because I’m a woman.” When I ran for speaker, it was “Don’t vote for me because I’m a woman. Don’t vote against me because I’m a woman. Listen to what I have to say.” And I think that she’s taking that path in her own right, very successfully.

Just because she’s not running [a campaign that focuses on the fact that she’s] as a woman, but as one who is for the whole country, she has great appeal to women for all that we want for women in the workplace—women to have access to quality, affordable child care, child tax credit, universal pre-K, family and medical leave, home health care—so women and men who are caregivers can have more success in the workplace. And she recognizes that women are entrepreneurs too. Her economic approach is about recognizing that if women are going to reach their full fulfillment, we need to help.

JN: There is much talk about the role you played, or may have played, in working with President Biden in this transition that saw him end his reelection bid and clear the way for Kamala Harris. How do you see what happened?

NP: The president made his own decision. He made a decision, and he said it so eloquently: “I love being president. I love this job, but I love America, our country, more.” That’s why he passed the torch. His legacy is a great one. I don’t think it’s fully appreciated, and we want to make sure that it is—because it’s not only his legacy; it’s our legacy as congressional Democrats as well. His decision is one that was selfless, patriotic, and courageous.

John NicholsTwitterJohn Nichols is a national affairs correspondent for The Nation. He has written, cowritten, or edited over a dozen books on topics ranging from histories of American socialism and the Democratic Party to analyses of US and global media systems. His latest, cowritten with Senator Bernie Sanders, is the New York Times bestseller It's OK to Be Angry About Capitalism.