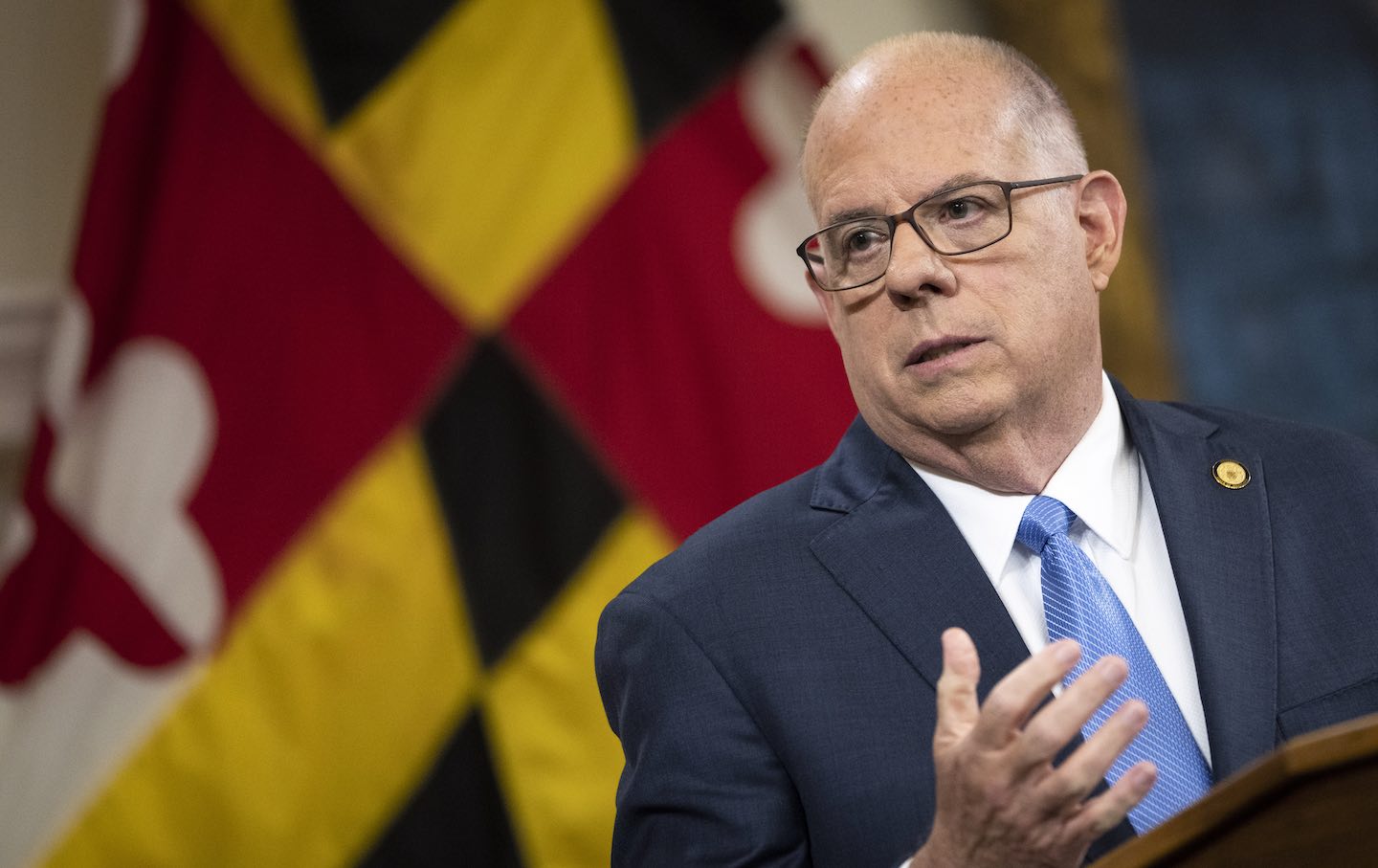

Maryland Governor Larry Hogan holds a news conference at the Maryland State Capitol on August 5, 2021.(Photo by Drew Angerer / Getty Images)

Former Maryland governor Larry Hogan says he still believes Republicans could win the presidency with an overwhelming majority if they would simply nominate a candidate like, well, Larry Hogan.

But the Republican who signaled in 2019 that he was giving “serious consideration” to challenging Trump for the 2020 GOP nomination—before finally deciding against doing so—once again won’t run. On Sunday, Hogan announced that he would skip the 2024 presidential race in which he had hoped to appeal to the party’s voters with an electability argument.

At least on paper, the case that Hogan had imagined himself making was credible. In a state that had not backed a Republican for president since 1988—and that gave Joe Biden 65 percent support in 2020—Hogan twice won the governorship by comfortable margins. In both of his bids, Hogan won a majority of the vote as an old-school conservative who avoided his party’s turn toward the hard right, openly broke with Donald Trump, and rejected “angry, divisive and performative politics.”

In deciding against entering the 2024 competition, Hogan purported to be optimistic about the prospects for a Republican politics that would do as well nationally as he did in Maryland.

“I still believe in a Republican Party that can win not just the electoral college or the popular vote but sweep landslide elections with an inclusive, broad coalition of Americans and a hopeful, optimistic vision for America’s future,” the former governor explained in a short essay that ended his exploration of a 2024 bid. “Some say this Republican Party is a relic of the past, but I disagree.”

The fact is that the United States is so deeply divided along lines of partisanship and ideology that it’s unlikely either party will—at least in the near future—run up big popular vote and Electoral College majorities. And if one side does figure out how to build the numbers, it’s likely to be the Democrats, especially if they end up running against the candidate who has already lost the popular vote twice and the electoral vote once: Donald Trump.

But if Hogan really believes in the prospect of a majoritarian Republicanism, why didn’t he test the theory with a bid against angry, divisive, and performative politicians such as Trump and Florida Governor Ron DeSantis?

The answer to that question is pretty clear. At the national level, the broad-base politics that Hogan proposes has been treated as suspect by Republican primary voters for decades. Ten years ago, Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein of the Brookings Institution and American Enterprise Institute wrote a book, It’s Even Worse than It Looks: How the American Constitutional System Collided With the New Politics of Extremism. In it, they argued that the GOP is “ideologically extreme; scornful of compromise; unmoved by conventional understanding of facts, evidence and science; and dismissive of the legitimacy of its political opposition.”

The conversion of the Republican Party into a rigid ideological vehicle occurred long before Trump entered politics, and it has cost what was once referred to as “the Party of Lincoln” the prospect of anything akin to a big win.

The GOP lost the House in 2018, lost the presidency and the Senate in 2020, and finished far worse than had been expected in 2022. But those are just the most recent measurements of its declining fortunes. Republicans have failed to win a majority of the vote in seven of the last eight presidential elections. The last Republican president to secure a majority of the vote in two consecutive presidential elections was Ronald Reagan, in 1980 and 1984. And the last to win the sort of overwhelming majorities that Hogan describes was Dwight Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956.

Eisenhower openly rejected and mocked extremists within his own party and on its fringe, arguing, “It is only common sense to recognize that the great bulk of Americans, whether Republican or Democrat, face many common problems and agree on a number of basic objectives.” In a letter to his brother, penned at a time when he was wrestling with the conservatives in the GOP, Ike wrote,

Should any political party attempt to abolish Social Security, unemployment insurance, and eliminate labor laws and farm programs, you would not hear of that party again in our political history. There is a tiny splinter group, of course, that believes you can do these things. Among them are H.L Hunt [and] a few other Texas oil millionaires, and an occasional politician or businessman from other areas. Their number is negligible and they are stupid.

Hogan isn’t as blunt as Eisenhower. But he twice supported Trump’s impeachment and once called for the Republican president’s resignation, a set of stances that positioned him more squarely in the accountability camp even than former US representatives Liz Cheney (R-Wyo.) or Adam Kinzinger (R-Ill.). Had he run for president in 2024, Hogan would have been the clearest alternative to Trump. It’s possible that, among the myriad potential contenders for the party’s 2024 nod, Hogan will find someone to back. But the likelihood that Hogan’s pick will be the nominee is roughly parallel to what it was in 2016, when he backed former New Jersey governor Chris Christie.

The harsh reality of the contemporary Republican Party is that, for all intents and purposes, it is no longer aiming to build broad coalitions and winning big majorities. This is a party that is ready and willing to win by the narrowest of margins. It has poured immense energy into projects at the state level to mangle election processes—with assaults on voting rights, gerrymandering schemes, and challenges to the legitimacy of results—so that it can keep on claiming “victories” without winning actual majorities. That’s what happened with George W. Bush in 2000 and Trump in 2016—both of whom lost the popular vote but secured Electoral College wins. Instead of treating those popular vote losses as cautionary signals, Bush and Trump governed as if they’d won big, by supporting massive tax breaks for the rich, appointing right-wing jurists, and claiming mandates that they never received.

For today’s GOP, the pursuit of a genuine mandate has, in fact, become a relic of the past. Larry Hogan may insist, “A cult of personality is no substitute for a party of principle.” But the current Republican Party operates differently. It nominated Trump in 2016 and 2020—and may do so again in 2024. If it doesn’t go with Trump again, it’s likely to go with a similarly extreme and bombastic “cult of personality” prospect such as Ron DeSantis. Hogan or someone who shares his values is not going to be the party’s nominee in 2024, or anytime soon.

John NicholsTwitterJohn Nichols is a national affairs correspondent for The Nation. He has written, cowritten, or edited over a dozen books on topics ranging from histories of American socialism and the Democratic Party to analyses of US and global media systems. His latest, cowritten with Senator Bernie Sanders, is the New York Times bestseller It's OK to Be Angry About Capitalism.