RFK Jr. Is Scary. His Online Fans Might Be Scarier.

To understand RFK Jr.’s rightward shift, we need to examine the Internet culture that fostered his growth—and which the Harris campaign ignored.

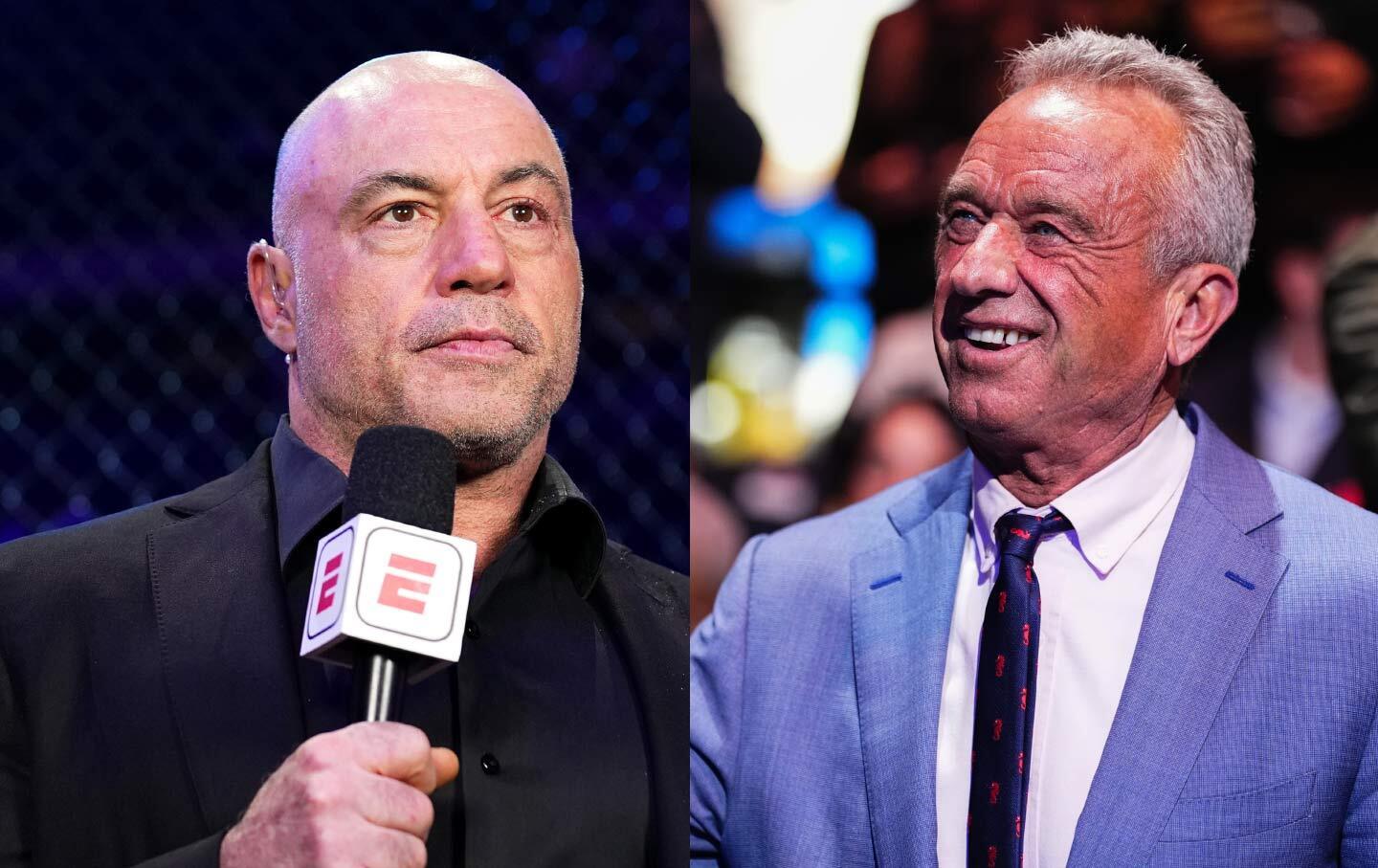

Joe Rogan and RFK Jr.

(Getty Images)

On November 8, three days after the election, the tech millionaire and human longevity influencer Bryan Johnson tweeted a photo of himself with his arm draped around Robert F. Kennedy Jr. It was captioned “MAHA,” or “Make America Healthy Again,” the slogan Kennedy adopted when he joined forces with Donald Trump in August after ending his own presidential bid. Six days later, President-elect Trump, announced Robert F. Kennedy Jr. as his pick for secretary of health and human services.

At this point, it should not be surprising that the man who may soon oversee Medicare would pose with a niche wellness influencer. Johnson, who made his millions on payment-processing apps, has become notorious for spending millions of dollars a year on interventions like young-blood transfusions, 100 daily supplements, and something called “penis rejuvenation” in a quest to become 18 again. He may lack Kennedy’s name recognition across generations and demographics, but the two men share key values: a commitment to personal health “optimization” and a skepticism toward mainstream medicine and Big Pharma. Most importantly, both exist within an ecosystem of New Age influencers that has for years drifted steadily rightward.

In 2016, Trump’s electoral success was famously boosted by an alt-right “meme army” of disaffected young men drawn from poorly moderated message boards like 4Chan and Reddit’s r/The_Donald. Through incessant posting, these anonymous online warriors helped drum up conservative and reactionary support for Trump. Since that time, his online base has only expanded and diversified: Young men, 56 percent of whom voted for Trump in 2024, have proven especially susceptible to the pull of right-wing Internet influencers. Many of their heroes are enmeshed in health-and-wellness discourse, even if their main brand is misogyny (Andrew Tate), tech (Elon Musk), or even “Judeo-Christian” family values (Ben Shapiro).

RFK Jr. began his career as an environmental lawyer committed to fighting large corporate polluters, and only recently defected from the Democratic Party. Over time, he has steadily raised his profile in online wellness circles, many of which are now overtly pro-Trump. In 2023, for instance, he convened a panel with some of the loudest anti-vax conspiracists on the Internet, including Dr. Sherri Tenpenny, Dr. Joseph Mercola, and Sayer Yi. Meanwhile, Kennedy’s MAHA slogan is directly pulled from the alternative health industry, originating with wellness magnates Calley and Casey Means. Right-leaning libertarian health influencers like Christian Van Camp frequently parrot Kennedy’s positions on “clean eating” and “sunshine”—although, when RFK Jr. appeared alongside a pile of McDonald’s hamburgers on Trump’s private jet, Van Camp joined those calling him out for hypocrisy. “This is why i don’t dive deep into politics,” Vamp Camp captioned his post.

In August, Kennedy drew praise from higher-profile figures like Joe Rogan after appearing on his show, which has upwards of 18.6 million subscribers. Rogan is not only a superstar podcaster but also a wellness guru who regularly recommends unregulated supplements, weight-lifting regimens, and intermittent fasting. Health influencers’ general regard for Kennedy is so great that, when he endorsed Trump, many of them did, too. In this context, the Bryan Johnson–RFK pairing—and indeed, Trump’s selection of Kennedy to head up HHS—is neither “weird” nor “out there.” It merely makes the connection between right-wing politics and seemingly apolitical lifestyle choices (avoiding seed oils, taking vitamins) to a new, more explicit level.

Kennedy’s rise is one symptom of a cultural realignment that has merged hippie-coded New Age wellness fads with right-wing conspiracy thinking. Whether we call it the “crunchy-to-alt-right-pipeline” or, as I have, “lifestyle fascism,” the politicization of consumer health choices has had dangerous knock-on effects, from lowering rates of vaccination to decreasing public trust in medical expertise. The tension between innocuous (if misguided) personal preference and potential public harm—and the blending of right, left, and centrist political commitments—comes through in Kennedy’s health policy “wish list,” which he tweeted shortly before the election. Some of his agenda items are recognizably right-coded, especially his endorsement of ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine, medications the Trump administration promoted as off-label “treatments” for Covid. Others, like “vitamins, clean foods, sunshine, and exercise,” might sound politically unaffiliated and even commonsensical. Yet, like so many once-neutral words, from “snowflake” to “liberal” to “patriot,” these terms have taken on new valences online. “Vitamins” now refers not just to supplements with proven effects, like zinc or Vitamin D, but to more exotic compounds like selenium and glucosamine. “Sunshine” sounds innocuous, but signals a disdain for sunscreen, which some health influencers allege causes cancer.

Some of the fads Kennedy and his supporters espouse emerged from left-leaning or even apolitical spaces, but are now more closely connected with conspiracy thinking than anything. Raw-milk advocacy, for example, has roots in leftist back-to-the-land movements of the 1960s and ’70s, but has attracted right-wing adherents since the Obama era. Similarly, homesteading, which has a rich history among anarchists, socialist land reformers, and feminist separatists, has, from about the 1990s on, become associated instead with right-wing prepperism, techno-libertarian utopianism, and conservative Christian movements like “quiverfull.”

In light of this realignment, it is time to stop thinking about the prospect of Kennedy in charge of American public health as a crisis of information or education, and start thinking about it as a crisis of culture. Since 2016, there have been calls to combat right-wing lies with fact-checking. But just telling the truth will not work on a base—and a political leadership—that has embraced the free intermixing of fact and fiction that defines life online. If we truly live in a post-truth era, we must accept that confronting people with facts does not change their minds. It’s also important to acknowledge that the convergence of conspiracy thinkers and wellness influencers is not some accident of the algorithm but a sign of widespread worries about the state of American public health. Healthful food has become extremely expensive since 2020, and potentially dangerous substances (including “forever chemicals”) pervade our food and water supplies. For the moment, Kennedy has assuaged these particular worries, convincing voters, as Trump did on the economy, that he will “fix it.”

Unlike Al Gore, Anthony Fauci, or any other mainstream Democrat concerned about environmental and health outcomes, Kennedy is a natural fit with the online wellness-industrial complex. He possesses no degrees or qualifications in, say, dentistry or epidemiology, but he’s tanned, youthful, and muscular in a way people associate with “health.” By systematically embedding himself within the world of health influencers, he has effectively become one himself—a Camelot-inflected version of Brian “Liver King” Johnson, who touts an “ancestral lifestyle” of raw meat and sunbathing.

In stark contrast to RFK Jr.’s media prowess, mainstream Democrats have failed to enter the fray. Kamala Harris’s decision not to appear on Rogan’s podcast, many have noted, was a major missed opportunity to connect with the young men who helped sweep Trump back into office. Her few attempts to capitalize on youth Internet culture—from taking photos with CharliXCX to campaigning as “brat”—fell flat because they were instrumental, not organic. Unlike Trump, Kennedy, and their surrogates, Harris lacked the long history of unscripted tweets, off-the-cuff remarks, and fresh-feeling mashups that would have made those gestures feel authentic.

Instead of going on Rogan’s show—perhaps to avoid a “backlash” from staffers—Harris courted voters with empty-sounding promises (“$25,000 for first-time homebuyers!”); radical truth-telling (“Trump is a racist, misogynist liar!”); and fearmongering (“the most important election of our lives!”). These strategies might have worked in 1996 or 2012, but are doomed to fail today. The problem is not that truth has ceased to exist but that facts no longer make good talking points. Information, true and false, quickly becomes Internet content today, which is delivered in personalized, isolated spaces to audiences that are increasingly polarized and specific in their interests. Coherence is no longer important, because people have short attention spans and easily integrate contradictory information into a patchwork worldview. Influencers like Bryan Johnson can take a seemingly heretical position, like questioning the demonization of seed oils, without damaging their brand. Similarly, Trump can flip-flop or spout nonsense (“concepts of a plan”) while maintaining credibility with his base. On November 5, his fans effectively bought a lifetime, nonrefundable subscription to his channel.

People are appropriately concerned about specific measures Kennedy could enact as head of HHS, from removing fluoride from state water supplies to discouraging measles vaccinations—something he actually did in Samoa in 2018, leading to a decrease in inoculation rates and a measles outbreak a year later. But counteracting medical misinformation and helping rebuild public trust in scientific institutions will require engaging with people—especially young people—where they live, think, and hang out: on the Internet.

Greater nuance in public health messaging is a laudable goal, but it does not directly address the mainstreaming of right-wing health-and-wellness culture, which has reached a new peak with Kennedy’s HHS appointment. Serious talk from establishment experts might help communicate with other members of that same establishment, or inform a segment of the public already willing to comply with conventional medical advice. What it won’t do is turn hearts and minds from Internet-mediated pseudoscientific obsessions. It’s too late not to elect Trump. But those of us who care about public health—and Democrats’ winning future elections—have to start taking the online world seriously. Our lives may depend on it.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Shocking Confessions of Susie Wiles The Shocking Confessions of Susie Wiles

Trump’s chief of staff admits he’s lying about Venezuela—and a lot of other things.

The King of Deportations The King of Deportations

ICE’s illegal tactics and extreme force put immigrants in danger.

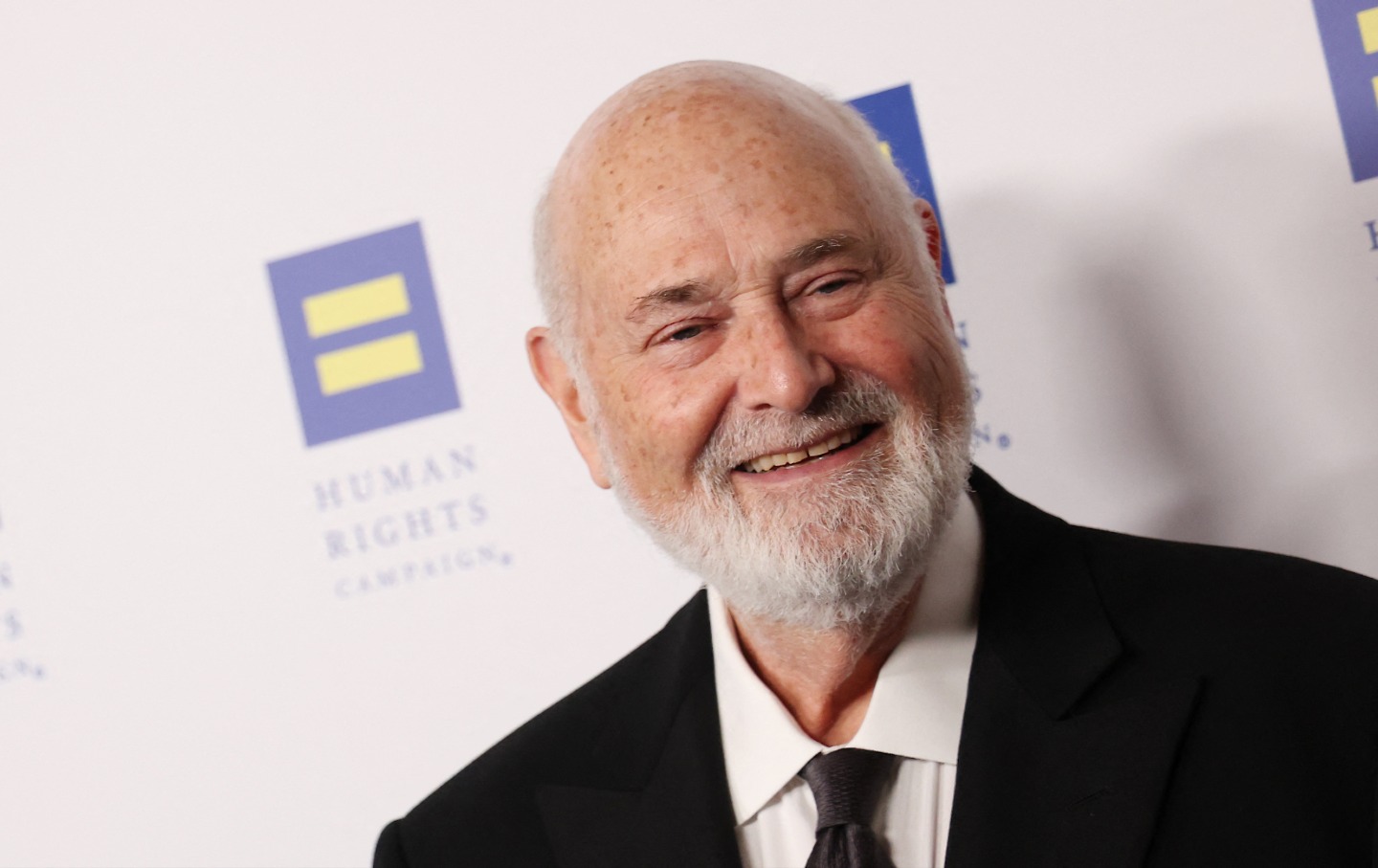

How Rob Reiner Tipped the Balance Against Donald Trump How Rob Reiner Tipped the Balance Against Donald Trump

Trump’s crude disdain for the slain filmmaker was undoubtedly rooted in the fact that Reiner so ably used his talents to help dethrone him in 2020.

The Economy Is Flatlining—and So Is Trump The Economy Is Flatlining—and So Is Trump

The president’s usual tricks are no match for a weakening jobs market and persistent inflation.

Trump’s Vile Rob Reiner Comments Show How Much He Has Debased His Office Trump’s Vile Rob Reiner Comments Show How Much He Has Debased His Office

Every day, Trump is saying and doing things that would get most elementary school children suspended.