The US Border Patrol’s community outreach efforts can verge on the macabre. For instance, agents at the Ajo station in Arizona, who patrol the Sonoran Desert for undocumented migrants, ran a Teddy Bear Patrol in 2004, passing out stuffed animals to small children. They did this while arresting immigrants trying to join their children after crossing the border.

Border Patrol Explorers, the agency’s program for 14-to-20-year-olds, offers an equally stark double standard: Young people, many of them first-generation Mexican Americans or the US-born children of undocumented immigrants, learn survival skills, first aid, and participate in training exercises in which they play Border Patrol agents or the people they target. Some will inadvertently retrace the path their undocumented parents took across the Sonoran Desert, pretending to get arrested or make arrests.

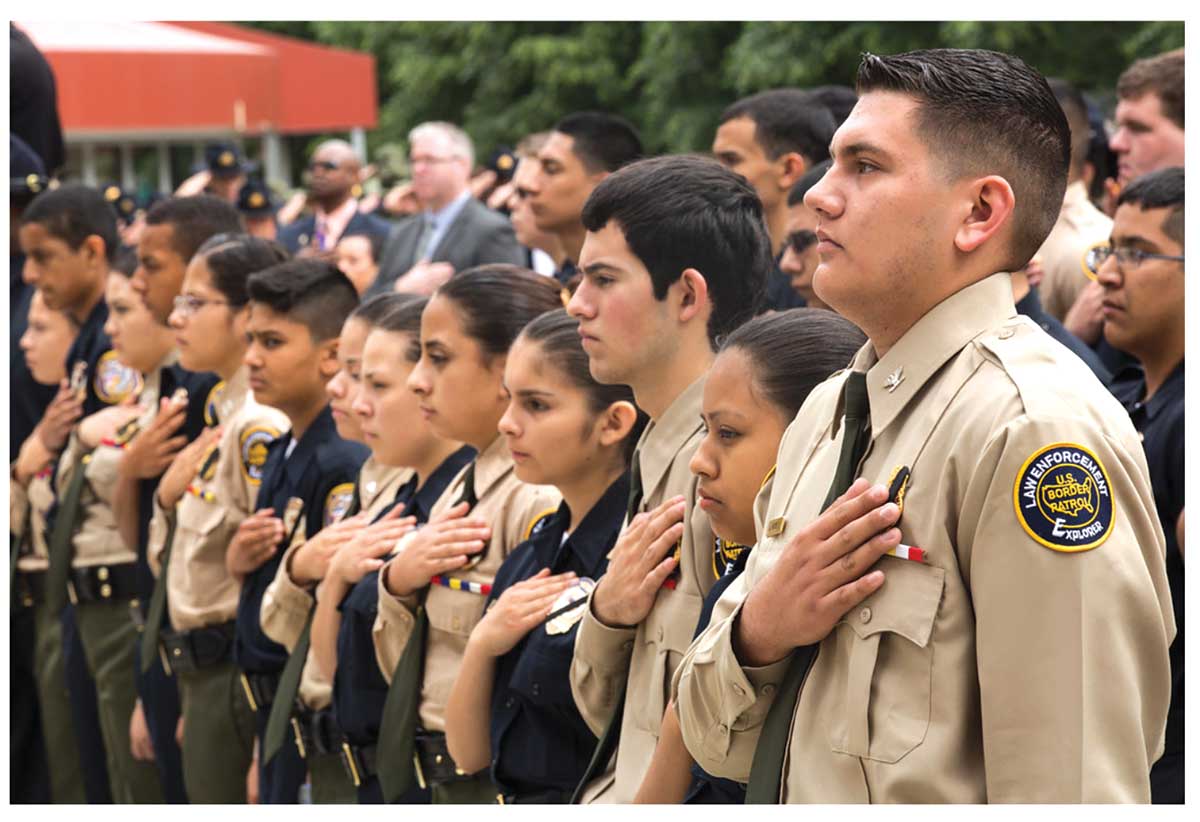

Operating in southern border communities throughout Arizona, California, and Texas as well as the northern parts of Maine, Michigan, and Washington, the Border Patrol Explorers program offers a taste of law enforcement work to young people interested in a career in security, policing, or the military. Run in conjunction with Learning for Life, an affiliate of the Boy Scouts of America, Border Patrol Explorers promises to teach young people life skills by preparing them, among other things, to arrest drug runners and undocumented immigrants. Various levels of law enforcement, from local sheriffs to the military, run their own Explorer programs.

I first came across Border Patrol Explorers in December 2018 while living in Ajo, an unincorporated former mining town in the Sonoran Desert. About 40 miles from the US-Mexico border, Ajo (population: approximately 3,300) is built around a Spanish Colonial Revival–style plaza and an enormous, inactive open pit mine streaked with teal and red from its oxidized copper. There’s a compound of Border Patrol homes north of the mine.

A former company town run by a revolving cast of businesses that constructed and once enforced segregated neighborhoods for its white, Mexican, and Native American workers, Ajo is now an important migrant crossing area with a complicated history. It is also, fittingly, the home of Scott Warren, an activist with the immigrant advocacy group No More Deaths who was arrested more than two years ago after giving water and shelter to two stranded migrants. (He was acquitted of felony charges late last year.)

I moved to Ajo after the family separation crisis of 2018. I wanted to understand the residents’ responses to President Trump’s deployment of the military to the border, and given the public outcry over the separated families, I was particularly curious to find out how young people understood what was going on. Many Ajo High School students commute from Mexico each day, and it’s not uncommon for families in town to have relatives on both sides of the border and drive across it frequently. One day, in the town’s central plaza, I encountered two freshmen on their lunch break who were chatting in Spanish on a bench.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →The boys told me about their hobbies, their skateboards, and what they wanted to do when they grew up: join the Border Patrol. Then one of their friends came over and mentioned that he was in Border Patrol Explorers. When I asked what that was, he opened up his phone and showed me a video of himself wearing safety earmuffs and a green uniform, firing a rifle into the desert. As I watched his body shake in the video from the weapon’s recoil, he looked up at me with a proud smile.

I spent the next several months trying to understand why this program existed and what its participants thought about it. But it was difficult to find any detailed information about the organization.

Apart from the sympathetic coverage of the Explorers by local TV stations and newspapers—limited mainly to the announcement of graduations, and community service days—little has been written about the program. US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and the Boy Scouts of America were hardly forthcoming; I contacted the Boy Scouts’ press office three times and various Border Patrol offices too many times to count, as well as the heads of Explorer posts, or units, in Arizona, California, and Texas. I was eventually given information about the program’s history and permitted to interview an agent in Maine, but I was never allowed to see a training session.

The Border Patrol’s press office in Arizona cited a personnel shortage and offered to schedule an appointment for me to sit in on a training period at a later date, but it dropped the ball after numerous further requests. I was eventually invited to attend meetings with Explorer posts in Laredo, Texas, and Douglas, Arizona—only to be turned away at the last minute from both. In Laredo, I arrived at the station and could see Explorers doing push-ups in the parking lot. That’s about as far as I got before I was told to leave.

Instead, I managed to interview four trainees, all of them boys (the girl Explorers I met declined to speak on the record.) I also interviewed Mark Phillips, a Border Patrol agent who started an Explorers post in Houlton, Maine. In addition, I obtained organization documents through a Freedom of Information Act request. The interviews and documents paint a picture of an organization similar to the youth outreach programs run by local police departments, except that the community-building and maturity exercises are focused on learning how to track and arrest people, including undocumented migrants.

The Explorers’ first post came into existence in 1984, thanks to the efforts of Border Patrol agent Gerald Tisdale to teach youths in Texas the duties and responsibilities of Border Patrol Agents. A former Boy Scout, he immediately forged connections with the local scouting council, which helped oversee the first group of 10 recruits in Laredo. Four years later, he was invited to Washington, DC, to help establish a national program. After its initial expansion to four posts in 1987, the Explorers grew to 45 posts by 2018, with 960 members in all.

In a telephone interview, Phillips detailed his experiences advising an Explorer post. He began his work with the CBP after serving in the military and established his post in Houlton in 2017. He said that running the youth group is one of the best parts of his job and that it is an important public service experience as much as a preparation for the Border Patrol in particular. He spoke quickly and enthusiastically about his post’s members, two of whom, he said, were able to administer crucial first aid to a man who was attacked by a rabid dog, using techniques they learned in the program.

Phillips explained that the Learning for Life program provides the initial training for agents interested in starting their own posts. It also issues broad guidelines regarding how the troops should be managed and then leaves the day-to-day management to these local agents. Each post requires participants to attend a basic law-enforcement academy, often in intensive sessions during the summer. According to a CBP press officer, the 60 hours spent in the Basic Explorer Academy instructs the teenage students in physical fitness, CPR, drills, and conducting vehicle stops. It also offers courses in radio communications, public speaking, report writing, and “ethics and integrity” and introduces the youths to criminal, juvenile, immigration, and Fourth Amendment law. Finally, the budding Explorers learn the history of the Border Patrol, along with the nuts and bolts of how the agency operates.

When it comes to patrolling, the techniques they learn vary by geography. In Maine, Phillips said, Explorers can receive training in operating the radar systems of Border Patrol boats. Explorers in Arizona practice footprint tracking suited to work in the desert. Many troops also receive training in firearm use, at times in outings sponsored by the National Rifle Association. Arrest and deportation trainings are standardized for posts across the country.

Each post pays for its own equipment, trips, and uniforms through fundraising. The troop in Houlton harvests vegetables for local food pantries and solicits donations in return. According to Nathaniel Madero, a 22-year-old Explorer alum from Douglas, Arizona, who joined when he was 14, his group paid for hiking trips by selling spent bullet casings they gathered after their firearm training sessions—like a bake sale but with weapons instead of brownies.

The first in-depth conversation I had with an Explorer took place two months after I started researching the group. He is Alexis Fabian, and he was a senior in high school. I had contacted him via Facebook after finding his name on the Border Patrol Explorers page for Yuma, Arizona. His profile pictures show a slight, proud-looking boy in an Explorers uniform, climbing rocks as part of an exercise.

Fabian, now 18, joined the Explorers at age 14. He had encountered recruiters at a local fair in Yuma, and later, his father’s friend encouraged him to join. (Agents often recruit Explorers at border town fairs, sometimes dressing as Agent Fino, the Border Patrol’s larger-than-life inflatable mascot.) In Yuma, Fabian said, advisers would take them to the levy where the Colorado River crosses the border, pointing out how men fishing there might be scouts helping to ferry migrants from Mexico. In the surrounding desert and in the Yuma Border Patrol station, his post would act out various enforcement scenarios.

“We would sometimes act as the agents,” Fabian said, “or we would be the illegals…. [The agents] would tell us who we were going to be, give us a little background on our life, and then we would act it out.” The supervisors would tell the Explorers playing “bad guys”—drug cartel members or armed immigrants—when the scenario involved a shooting, then encourage them to catch the border agents off guard.

Photos from the Yuma and Tuscon Explorer pages on Facebook show the trainees peering from behind CBP trucks or hiding behind creosote bushes and pointing mock weapons at suspects in the distance. Videos show them training in the desert or jumping out from behind dry brush to make an arrest. They run in formation, weaving in and out of cover, seeming to treat the desert like the set of a wartime thriller. Fabian recalled that he and his peers would shout “Bang! Bang!” to indicate when they were shooting someone. Other groups of Explorers carry airsoft guns that shoot plastic pellets and layer several T-shirts to protect their chests.

Fabian explained why his post would practice shooting. “Sometimes [undocumented immigrants] are not compliant when we find them,” he said. “They paid all this money to get here to start another life. They’re not just going to give up when they see us. Some would fight back. Some would be compliant. Maybe they try to kill you or threaten you. Sometimes they pick up an element—a rock lying around, anything. Anything can be used to kill you.”

He added that the Explorers are always instructed not to shoot to kill but rather to disarm immigrants and protect agents.

Another common scenario would involve simulating high-risk vehicle stops at Border Patrol checkpoints, which are scattered across Arizona’s highways. In these exercises, the Yuma Explorers would sit in parked cars, pretending to be migrants, while other Explorers interrogated them through the window. The aspiring agents were supposed to project “officer presence,” or an air of authority, as they attempt to untangle the lies of the migrants, Fabian said.

While role-playing as a migrant, he said, he would often encourage other Explorers to be more authoritative. “If the Explorer didn’t have officer presence, if they looked nervous, I would be rude to them,” he added. “If they stuttered with their questions to me when they’re supposed to be the ones with power, I would be rude or wouldn’t talk.”

Along with the other Explorers I spoke with, Fabian said that learning officer presence was an important part of his development as a person; it taught him confidence. That this confidence comes from wielding power over one’s friends, who are role-playing as immigrants, in a program co-run by a national law-enforcement agency, is a fitting reminder of the increasingly xenophobic ideologies embraced and spread by the nation’s highest office.

Other activities teach even more life lessons. The Chandler Tactical Competition in Arizona brings together Explorer troops from different levels of law enforcement across the Southwest to compete in challenges ranging from crisis negotiation to raiding marijuana fields (in which the teens traverse booby-trap-laden fields wearing combat gear).

A YouTube video produced by the Chandler Police Department features scenes from the 2017 competition. Opening with a faux MPAA advisory reading that the video is “rated R” for “some strong, intelligent participants throughout,” it has a James Bond theme. Actor Daniel Craig points his gun at the camera, and Judi Dench looks on as a building explodes; an overhead shot, presumably taken by drone, pans across lines of young Explorers carrying firearms, and a bomb made from Coca-Cola cans and a cell phone displays an incoming call with Arabic script. One teen mock-shoots another teen point-blank. Early frames read, “You cadets & explorers, bring out your inner Bond. Starring you as Bond 007.”

If there’s something overtly theatrical, even campy, about these recruitment efforts, that isn’t a coincidence. The age-old children’s games of cowboys and Indians or cops and robbers have simply been harnessed for a modern, state-run, militarized equivalent: border guards and immigrants.

The city of Douglas, Arizona, even saw a collaboration between the local Explorers troop and the Douglas High School Drama Club in 2015 after high school actors agreed to play criminals to help raise the emotional stakes of their training.

The theater kids recalled enjoying playing school shooters, armed robbers, and domestic abusers. They were so affecting in their performances, according to former theater club member Nelva Valenzuela, that one of the Explorers told her that the participant “almost cried” during a training exercise. In some exercises, her fellow actors got so caught up in their roles that they began to defeat the mock agents. They eluded arrest with elaborate dialogue and tricks, leading the Border Patrol agent to remind them to “let Border Patrol win.”

That’s what tends to happen in real life, too, in no small part thanks to recent obstacles imposed by the Trump administration that make it exceedingly difficult for anyone to seek asylum—from categorizing victims of domestic violence as ineligible to requiring individuals traveling from countries south of Mexico to seek shelter along the way first.

Children are taught the basics of these laws in Basic Explorer Academy, Phillips said. One of the main parts of the law curriculum, he added, involves clarifying the distinction between defensive and affirmative asylum processes. A defensive process, per the government, is one that migrants initiate in order to avoid being deported—say, after being arrested for crossing the border without the right documents or on suspicion of committing some other crime. An affirmative process for asylum in the US is one started without removal proceedings or any other kind of legal charges hanging over the migrants’ heads.

To Phillips, the difference between the two generally boils down to criminals (defensive claimers) and noncriminals (affirmative claimers). “Should those two [kinds of] people be treated the same, or should they be treated differently?” he asks.

But it’s not that simple. A major reason most asylum claims are now made defensively is that since 2005, crossing the border outside a designated port of entry has been enforced as a criminal, not a civil, violation. This lands migrants in removal proceedings before they’re able to make an affirmative claim at all.

Paired with Trump’s newer restrictions narrowing who is eligible for asylum, seeking asylum legally at the southwestern US border has become virtually impossible.

When I tried raising these objections, Phillips interrupted, insisting the difference was still between “a convicted child rapist” and “a politically persecuted individual” who doesn’t “want to return to their dictatorship country”—a black and white version of the border crisis you might hear from Trump himself.

The ideology baked into the Explorers’ curriculum isn’t lost on participants. Erick Gomez Lopez, a 22-year-old alum and aspiring border agent from Ajo, went on a trip with his post to a nearby Border Patrol station. A soft-spoken young man, he met me after his custodial work at a local health clinic and rubbed his baseball cap throughout our conversation. “The doors to [their] cells were left open,” the detainees were “given snacks,” and the people were “not treated like animals,” he said, adding that he didn’t think they were being treated badly. And yet Lopez seemed uneasy, saying, “They were staring at me.”

Later I asked an Ajo Explorer, Ilian Aguilar, what he thought about the migrant deaths around his hometown and the bones and personal belongings regularly found in the surrounding desert.

Aguilar, who’s in his late teens, said that the deaths were “a touchy subject” and he “didn’t know what to think about them yet.” Then the conversation returned to how much the Border Patrol has helped him grow.

Former Explorer Madero said that while he had no problem with others joining the Border Patrol, he didn’t pursue a job with it because he didn’t think he “could handle or would like work as an agent.” But working at the local jail, he has found it hard to avoid those issues entirely. “When Border Patrol arrests immigrant[s], they come to us…. They were probably trying to get away, trying to come here for a better living. But now they are in jail…before they go right back home.”

In Ajo’s central plaza, the trainee who showed me the video also said he knew that migrants are not criminals and are simply seeking to improve their circumstances. I asked why he continued to participate in the program. “Money,” he replied. “Money, money, money.”

Ajo’s median household income is just over $33,000, and just under a third of its residents live below the federal poverty line; when the highest-paying jobs in town are in law enforcement, working for Border Patrol makes economic sense.

The moral case for this career path is less clear, and without precise figures from the CBP, it’s hard to tell if participation in the Explorers has dropped as public awareness of family separations, assaults and deaths in detention, and other scandals has spread.

In the Maine borderlands, at least, Phillips said, the Explorers program was on hold last year because there weren’t enough advisers to run it. The “humanitarian national security crisis at the border” had forced them to deploy down south, he said, but now that apprehensions are down, “we’re back at our full contingent of advisers.”

They’re holding meetings twice a week.