A Close-Up View of the UK Election Gave Rise to an Unfamiliar Emotion: Envy

The US left can only dream of Democrats’ having five years ahead of interrupted power—and control of Congress—with the GOP, like the Tories, driven far to the margins for a decade.

London—When I saw Keir Starmer here in late June, less than a week before the Labour Party would secure one of the great parliamentary majorities in British history, he was headlining a campaign rally, promising change while warning, with far more vigor, against prolonging the crisis of Conservative governance. Starmer, or Sir Keir—he was knighted a decade ago—is not a politician, as many have observed, to stir the blood. To American eyes, he blended the charisma of Jeb Bush with the ideological slipperiness of Hillary Clinton. Used to the garish, if occasionally thrilling, campaign theater of the United States, I was struck by the intimate dimensions of the gymnasium that comfortably contained the entire red-shirted Labour crowd. It seemed more like a congressional candidate’s confab somewhere in suburban New Jersey than a rally for the future leader of the world’s sixth-largest economy–the second-largest in Europe, after Germany.

But to no one’s surprise, a few days later Labour won, ending 14 years of dismal Conservative rule. Given his 412 seats—a whopping 174-seat majority—Starmer and his party will have an ironclad grip on the government of the United Kingdom for the next five years.

What does this have to do with the United States?. There is little chance our own center-left party, the Democrats, will win full control of the government this fall. Even if Joe Biden—currently trailing Donald Trump in the polls and battling back calls to step aside after the worst televised debate performance in American history—manages to eke out a victory, few now hold out much hope of the Democrats’ even retaining control of the Senate. And Starmer, a former prosecutor and human rights lawyer—not to mention a full two decades younger than Biden—is able to fluidly, if uninspiringly, communicate with his public as the new prime minister.

The British can also take comfort in the fact that their far right is nowhere the levers of power. There is no British Trump or Marine Le Pen looming, while their own rank nativist, Nigel Farage, far from threatening to storm 10 Downing Street, instead merely added to the margin of Labour’s victory by siphoning votes from Rishi Sunak, the Conservative prime minister Starmer vanquished, and (apart from his Indian origins and brown skin) a prototypical wealthy Tory. Britain’s closer Trump analogue, Boris Johnson, was chased from power by scandal, and in any case will have scant influence over a political system dominated by Labour.

Americans on the left can only dream of the Democrats’ having five years ahead of them of interrupted power, with the GOP driven so far to the margin that they may not recover for another generation. The rest of this decade will belong to Starmer—just as the 1980s belonged to Margaret Thatcher or the late 1990s and 2000s were the domain of Tony Blair’s New Labour.

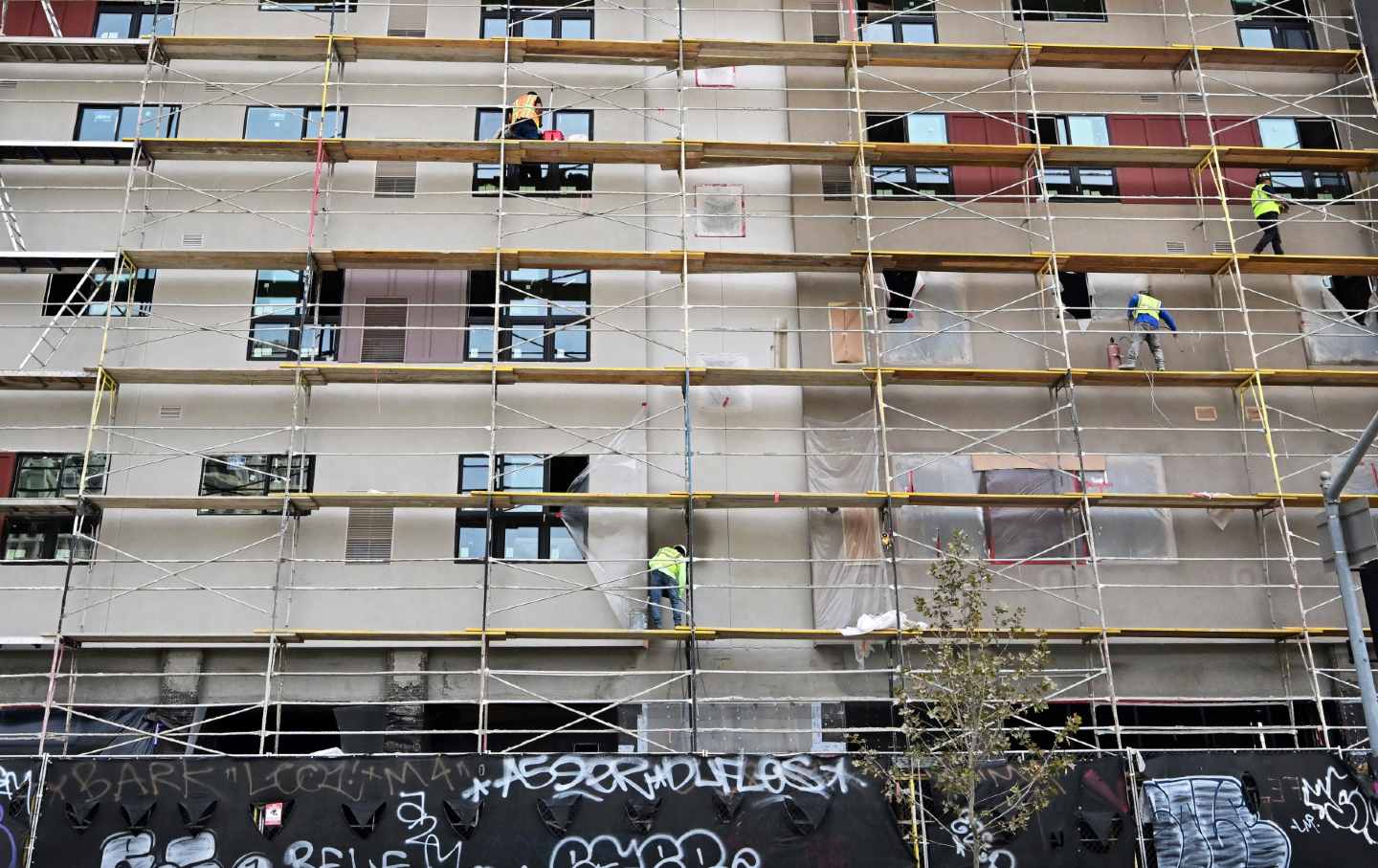

To the dismay of some on his left, Starmer won by tugging Labour to the center, offering an agenda tailored to the broadest number of British voters. He promised to rebuild the fraying National Health Service, reverse Conservative-imposed austerity, and build many more homes to address the UK’s desperate housing affordability crisis. He promised to hire more police to crack down on knife crime (gun violence is a uniquely American scourge) and combat so-called “antisocial behavior” like public urination, drunkenness, and drug-dealing—a populist as well as popular pledge. Like Biden, who authorized a tightening of the southern border in the vein of Trump, Starmer triangulated on immigration, pandering to nativist sentiments enough to even antagonize the Bangladeshi community, a longtime Labour constituency. He also alienated Muslim voters by refusing to recognize Palestinian statehood. This is not Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party. (Despite furious Labour opposition, Corbyn retained his North Islington Parliamentary seat, and remains in Parliament as an independent.)

Yet the triumphalism of the new centrists and old Blairites masks the frailty of Labour’s sweeping victory. Starmer is not Franklin Delano Roosevelt at the dawn of the New Deal era. Britain is a nation—not unlike the United States—where disdain for the two major parties has reached a historic zenith. Conservatives and Labour won their lowest combined vote share ever, with Labour actually garnering fewer votes than in either of the elections helmed by Corbyn. The British masses were far more forcefully opposed to the Tories than enraptured by Starmer’s Labour Party. Labour built its margins, in part, with the help of the collapse of Scottish National Party, as most Scots decided they preferred Labour to any lingering hope of breaking away from the UK. Voters on the right deserted the Conservatives for Nigel Farage’s anti-immigrant Reform Party, which won 15 percent of the overall vote and sent Farage to Parliament for the very first time. Disgust with the Tories handed the centrist Liberal Democrats more seats, too.

On the left, the Greens made unexpected gains—even taking a Labour seat from shadow cabinet minister Thangam Debonnaire. Labour’s election campaign coordinator, Jonathan Ashworth, lost his Leicester South seat to an independent pro-Palestinian candidate, Shockat Adam. Adam was not alone, with four other independents carrying seats with large Muslim populations. Democrats should take heed: Enough defections from Muslim and Arab voters could similarly damage them in Michigan, a pivotal swing state.

If the United States is an ailing nation by any reasonable human metric—too many poor, too many sick, too much wealth in too few hands, and, post-pandemic, even a declining life expectancy—Britain is gripped by a malaise that Labour cannot easily chase away. Inflation grinds on. The Tories strangled growth through repeated and demoralizing budget cuts, shredding a social safety net that was once the envy of the Western world. Britain, according to the United Nations, now has more children in poverty than any other wealthy country. Apart from London, some estimate it is poorer than Mississippi. The most tangible Conservative Party legacy beyond austerity, Brexit, has alienated voters across the ideological spectrum, throwing up fresh barriers to business while failing to uplift the working class, who believed departing the European Union would vastly improve their lot. Starmer will not bring Britain back into the European Union but even if he publicly longed to reverse Brexit, European leaders, preoccupied with the war in Ukraine and the onward march of the far right, don’t care any longer about the fate of the British, either way. The American empire may be fading, but it will never be so irrelevant.

The British national mood, as the writer Sam Kriss pointed out, remains grim. The UK’s GDP per capita is half that of America’s; beyond the glitz of London, British towns have withered. England, strangely, is the only country with a fully privatized water and sewage system, and politicians are forced to talk tough to the water-industry bosses dumping raw sewage into the rivers. The poor have gotten poorer, while corporate profits have mostly flatlined over the last decade and a half. Whereas, in America, talk of politics inevitably takes on the mania of end-time proselytizing—the outcome of this election could obliterate the country for good—the British are under no such illusions. Instead, they seem to have given up hope that their political system, might change much in any direction.

Still, a Labour government can improve lives by simply reversing the most brutal Tory cuts. Social services, public infrastructure, and the arts will all benefit from the end of supply-side dogma. But Starmer has already dialed back bolder promises. Labour’s green investment plan—the purview of former Nation intern Ed Miliband, newly installed as secretary of state for energy security—has shrunk to £5 billion ($6.4 billion) a year, down from £28 billion. A workers’ rights package—ending bosses’ power to arbitrarily fire and rehire, while introducing rights to parental leave, sick pay, and protection from unfair dismissal—has already been weakened following criticism from big business. The two-child benefit cap—which limits certain state support payments to two children regardless of actual family size—will remain. Starmer has promised to bolster social services without raising taxes, relying instead on nebulous initiatives to boost economic growth and using the resultant surplus to return Britain to brighter days. There are plans to close a private-equity tax loophole and strip the country’s elite private schools of their tax-exempt status, while raising more cash by targeting widespread tax avoidance. Easier said than done.

What Britain lacks—at least to this foreign tourist—is American dynamism and verve, as well any immediate hopes of resurrecting its industrial base. Biden, to his credit, has spent much of his presidency laying the groundwork for an eventual manufacturing boom, especially for essential semiconductor chips. Starmer has promised to create a state-owned energy company, but he will need to contend with decades of diminished public capacity. His honeymoon won’t last long. If the British horizons feel constrained, there is still a certain comfort that can be derived in the Labour takeover. Politics will be sober and fairly predictable. The Conservatives may veer rightward in a bid to capture the votes lost to Farage’s Reform. A Le Pen–like figure, at some point soon, could capture the party’s leadership. The Tories, though, will be in the wilderness for five years—or, perhaps, much longer. Historically, the British often keep one party in power for more than a decade.

The American system, meanwhile, remains far more byzantine—layers of local and national governments in conflict, a revanchist Supreme Court increasingly invalidating hard-won rights over the last half century—and deeply volatile, with most of the nation herded into two bitter camps: anti-Democrat and anti-Republican. Without a parliamentary system, there is no meaningful outlet for the millions of voters who’d prefer third parties, and with the pox of the Electoral College, minoritarian rule may be our fate again. By November, Starmer-style muddling may well be something to envy.

More from The Nation

It’s Official: The People, Not the Politicians, Are Leading It’s Official: The People, Not the Politicians, Are Leading

In this week’s Elie V. US, our justice correspondent explores the fecklessness of the Democratic Party, MAGA racism, and fighting despite unwinnable odds.

The Week of Colonial Fever Dreams From a Sundowning Fascist The Week of Colonial Fever Dreams From a Sundowning Fascist

The news was a firehose of stories of authoritarian behavior. We can’t let ourselves drown.

Self-Appointed King of Venezuela Self-Appointed King of Venezuela

The United States attacks Venezuela and captures President Maduro. Trump claims that the US will “run” the country for oil interests.

Why the “Abundance” and “Stuck” Crowd Are Off the Mark Why the “Abundance” and “Stuck” Crowd Are Off the Mark

Don’t blame the housing crisis on local NIMBYism and too many regulations.

Democrats Need to Shut Down the Government to Defund ICE Terror Democrats Need to Shut Down the Government to Defund ICE Terror

With another deadline looming at the end of the month, party leaders must use the power they have to begin dismantling Trump’s police state.