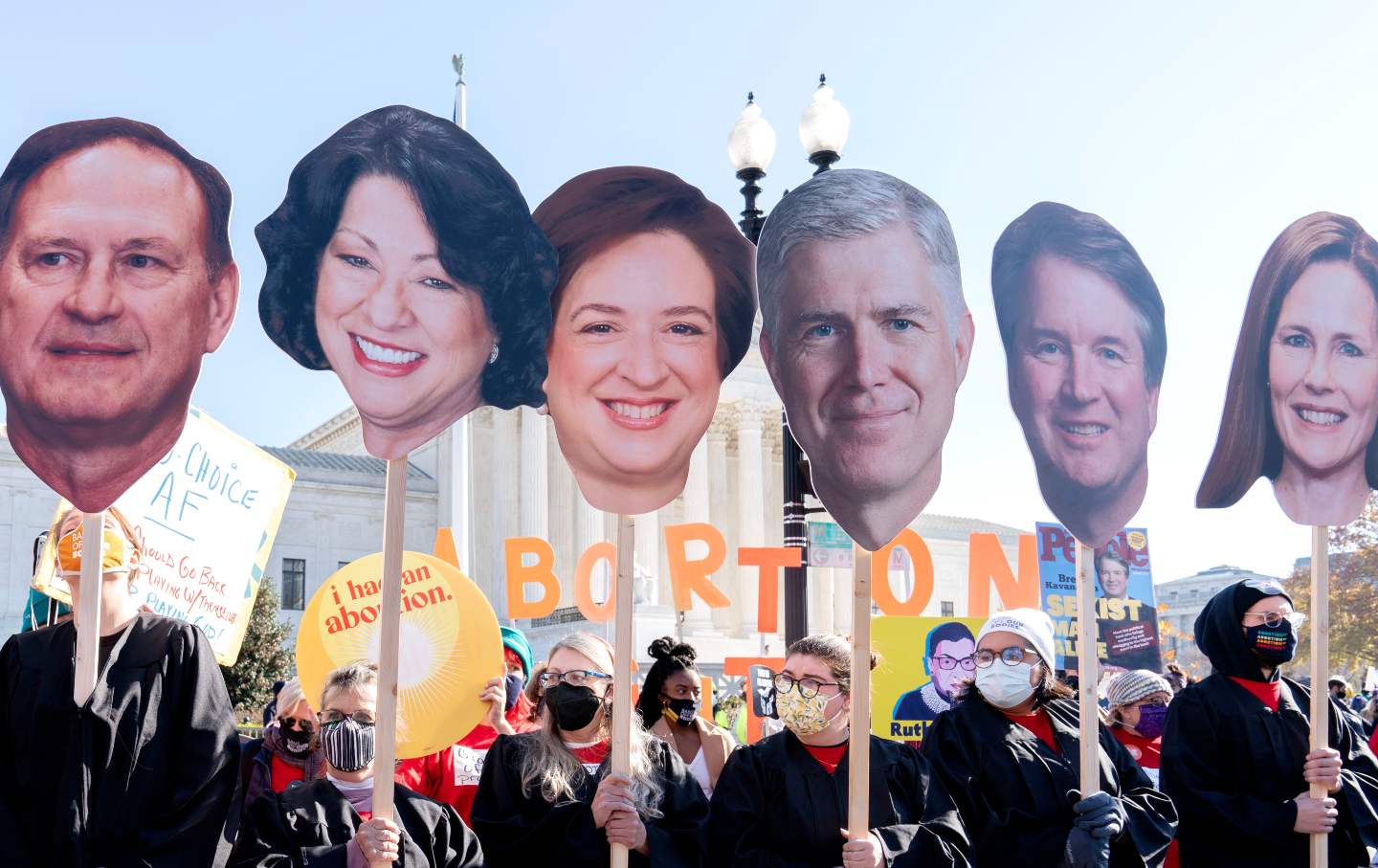

Abortion rights advocates holding cardboard cutouts of the Supreme Court Justices demonstrate in front of the US Supreme Court Building on Wednesday, December 1, 2021. (Jose Luis Magana / AP Photo)

When Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his retirement on January 27, 2018, farsighted observers like New York Senator Chuck Schumer accurately predicted that he’d be replaced by a nominee who would help end Roe v. Wade, Casey v. Planned Parenthood, and the constitutional right to an abortion. On July 3, 2018, The Wall Street Journal published an editorial mocking those claims as “the abortion scare campaign.” According to the Journal, “The liberal line is always that Roe hangs by a judicial thread, and one more conservative Justice will doom it. Yet Roe still stands after nearly five decades. Our guess is that this will be true even if President Trump nominates another Justice Gorsuch. The reason is the power of stare decisis, or precedent, and how conservatives view the role of the Court in supporting the credibility of the law.”

The editorial went on to note Chief Justice John Roberts’s sharp dissent on the 2015 Obergefell v. Hodges case establishing marriage equality, but added that “there’s almost no chance the Chief would would reverse Obergefell now. Tens of thousands of gay couples have been married across the U.S. since the ruling.”

The editorial was an exercise in reassurance: an attempt to sooth anxious liberals and centrists worried about how far the court would go after the relatively moderate Kennedy was replaced by a right-wing judge. Don’t worry, the Journal told readers; the court respects precedent, respects Roe, and respects Obergefell.

On Friday, of course, that Journal editorial joined the long list of journalistic embarrassments with the release of the Supreme Court’s decision on Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Dobbs completely overturns precedent in Roe (1973) and Casey (1992) in order to extinguish the constitutional right to an abortion.

If The Wall Street Journal was wrong about Roe, isn’t it likely that it will also be wrong about Obergefell? After all, these two cases don’t exist in isolation but as part of a network of mutually reinforcing legal decisions upholding sexual freedom as part of an inferred right to privacy. Other major decisions in this legal structure include Griswold v. Connecticut (the 1965 case that recognized the right to birth control) and Lawrence v. Texas (the 2010 case that struck down anti-sodomy laws).

All the current Supreme Court justices are very aware that these decisions are intricately linked, so that to dismantle one case risks bringing the whole structure tumbling down. This is the root of the legal drama that can be found in the Dobbs decision written by Samuel Alito, along with Clarence Thomas’s concurrence and the dissent from the liberal judges. These three statements offer sharp disagreements about whether the whole structure of American sexual freedom is in danger—or whether the impact of Dobbs will be only on abortion.

In their dissent on Dobbs, Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elana Kagan invoke the homely metaphor of the children’s game Jenga, where the trick is to pull blocks out of a wooden tower without causing it to come crashing down. “Faced with all these connections between Roe/Casey and judicial decisions recognizing other constitutional rights, the majority tells everyone not to worry,” the dissent sarcastically observes. “It can (so it says) neatly extract the right to choose from the constitutional edifice without affecting any associated rights. (Think of someone telling you that the Jenga tower simply will not collapse.)”

In his concurrence, Thomas in effect agrees with the dissenting judges on their Jenga metaphor. He thinks Roe was badly decided in ways that parallel Griswold, Lawrence, and Obergefell. They are all fruit of the same poisoned tree, in Thomas’s view. Thomas asserts that the court has a “duty” to “correct the error” of those earlier decisions.

Thomas certainly has logic on his side; he is able to effectively quote fellow conservative Supreme Court justices such as Samuel Alito and John Robert excoriating those earlier decisions in the exact terms the Dobbs decision uses against Roe and Casey.

Perhaps because of the potent logical coherence of Thomas’s position, both Alito in the main decision and Justice Brett Kavanaugh in his concurrence go out of their way to insist that they do not want to touch those earlier decisions. In language reminiscent of the Journal editorial, they proclaim great respect for precedent. Writing in Reason, legal scholar Dale Carpenter says he counts “no fewer than four places in the Dobbs opinion that disavow any implications for other rights. I refer to these as the reassurance passages. Two of them were already in the leaked draft opinion. Two more have been added because they are responses to the dissent (which would not have been available when Justice Alito circulated his first draft in February).”

Carpenter takes these “reassurance passages” at face value. But should we really trust Kavanaugh, who during the nomination process made weaselly and deceptive assertions of his respect for precedent when asked about Roe? The “reassurance passages” in his concurrence have the air of protesting too much, of trying to wave aside anxiety with the use of italics. But as a logical exercise, Kavanaugh’s argument lacks the coherence of Thomas’s analysis.

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation

The same is true of Alito’s decision. Alito writes derisively about Griswold, Lawrence, and Obergefell, but says they are safe because the issues they involve don’t approach the importance of the debate over the value of fetal life. But if those decisions are, in Alito’s views, badly reasoned, doesn’t Thomas’s claim of a “duty” to “correct the error” have urgency? Even Dale Carpenter admits, “It is true, as both Justice Thomas and the dissent point out, that rights to contraception, sexual intimacy, and same-sex marriage do not fit easily within the Court’s narrow history-and-tradition methodology. That might spell longer-term trouble under a different cast of Justices who may not feel as much obligation to ancestral precedents.”

But there is no need for a “different cast of Justices,” since the existing six conservative justices are already opposed in principle (and often in their previous decisions) to Griswold, Lawrence, and Obergefell. And five of those six have shown a willingness to overturn a major precedent. It’s only a matter of time before they act on the logic of their stated position.

Ultimately, this is a matter more of political momentum than of legal reasoning. Roe and Casey were overturned by Dobbs because of the power of a tenacious conservative legal movement. This movement has an infrastructure—built by plutocratic money—that has allowed it to vet judges (the Federalist Society), build and nurture institutions to agitate for social conservatism (mainly the evangelical churches), and create political pressure groups to prod lawmakers at the state level to craft laws that can be taken up by the courts.

The conservative legal movement is an impressively financed and organized multigenerational political project. It’s been able to learn lessons from its defeats (the rejection of Robert Bork’s nomination, the ideological apostasy of David Souter and Anthony Kennedy) and to nimbly seize opportunities to expand power (as with the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg).

Does anyone believe that the conservative political movement will disappear after its great victory in Dobbs? That, having come so far, it will now declare “mission accomplished” and close up shop? Or will it be emboldened by victory to push even further?

The members of the conservative legal movement don’t like LGBTQ rights and they believe (wrongly) that many forms of birth control are in fact abortifacients. There is no reason to think they will settle for triumph over Roe. They’ll want more. They’ll pass laws in red states that will push the limits on rolling back marriage equality, access to birth control, and LGBTQ rights in general. And they will push to have these cases taken up by the Supreme Court. The conservative judges on the court will then be forced to confront the logic of their previous positions.

Last week should have taught us not to accept the glib reassurances offered by Alito and Kavanaugh. As often, Thomas is the more bluntly honest figure. When Thomas promises to “correct the error” of earlier courts on birth control and gay rights, we should take him at his word.

Jeet HeerTwitterJeet Heer is a national affairs correspondent for The Nation and host of the weekly Nation podcast, The Time of Monsters. He also pens the monthly column “Morbid Symptoms.” The author of In Love with Art: Francoise Mouly’s Adventures in Comics with Art Spiegelman (2013) and Sweet Lechery: Reviews, Essays and Profiles (2014), Heer has written for numerous publications, including The New Yorker, The Paris Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, The American Prospect, The Guardian, The New Republic, and The Boston Globe.