Christiansburg, Va., resembles many other towns in the United States. There’s a small city center surrounded by strip malls, and the vast sprawl is where most economic activity occurs. Given that these corporate landscapes now dominate the country, maybe it’s appropriate that this is where a radical labor movement is taking shape.

This project was made possible in part by support from the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

In the basement bedroom of his parents’ small brick house along a hilly Christiansburg back road, Adam Ryan, a 31-year-old part-time sales associate at Target, has amassed a tool kit for revolution: a megaphone, research reports and fliers, and hundreds of books—biographies of Vladimir Lenin and Karl Marx, histories of Jim Crow and capitalism, and guides about organizing workers and the benefits and limits of unions.

This room has become an unlikely organizing center. Ryan wants to help build a workers’ movement that does not rely on unions or nonprofits to educate or organize and instead trains the workers to do it themselves. The problem, according to him and others doing similar work, is that the big traditional unions have had their missions whittled down. They no longer fight to have workers at the levers of power, preferring to bargain for better conditions at specific companies. That has alienated radicals like Ryan. They don’t want just a better contract. They want a worker-controlled future.

Ryan is guided by the belief that nearly everything good for labor will not be accomplished by paid organizers, nonprofits, or lobbying groups but will have to come from low-paid workers.

The result is Target Workers Unite, a group that Ryan created in 2018 and has had involvement from Target employees across 44 states. There are currently about 500 TWU members, and that number is rapidly growing through the Covid-19 crisis as workers struggle to pay their bills and deal with managers who have underplayed the disease’s threat and with a corporation that has, like many of its ilk, refused to give employees comprehensive paid sick leave.

“Folks are becoming more agitated,” Ryan told me. “I think that leaves us with a good basis to organize our coworkers. I’m hoping that’s the good thing that can come out of all this, that we come out of this more organized and unified as workers—as essential workers.”

TWU was birthed partly out of his frustration with the organizing that the unions were doing with retail workers. Before moving back to Christiansburg, Ryan was living in Richmond, Va., and held a string of restaurant and retail jobs. At each, he tried to organize workers, but he said the unions didn’t lend enough support.

With the Industrial Workers of the World, Ryan said, he felt they were just telling him, “Let’s run everybody through the organizer training and then tell everybody to just go organize their workplaces,” without much continued support.

And he said it seemed the big groups, like the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union (UFCW), had too much of a top-down approach: They come in, help you get set up, help negotiate your contracts, then leave. For Ryan, there wasn’t enough of an emphasis on politicizing workers. Many unions, he said, want to smooth over the worker-boss relationship. He wants the opposite; he wants to agitate it.

As the protests in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd spread, Ryan tried to talk to his fellow Target employees about how issues of labor, racism, and policing are related. Floyd was killed in Minneapolis, where Target has its corporate headquarters and where the company has formed a close relationship with the police. But many of Ryan’s coworkers have pushed back on his attempts to show the links. He said some of his colleagues are so accustomed to labor organizing being siloed from issues of race that he has found it hard to convince them that the fight for higher wages and the fight against the racist American justice system can be one and the same.

“We need to be pointing out how these things are connected,” Ryan said. “[The mainstream] unions ignore all those connections.”

It’s not that he is anti-union. He’s not against joining one in the future, but he said trade unions have lost their way. Gone is the anti-capitalist rhetoric of the early and mid-1900s, during which unions supported workers seizing factories. Now unions represent the police Ryan would like to organize against.

Targeted: On May 1, Target Workers Unite organized a sick-out to protest the lack of safety measures and protective equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic.(Courtesy of Target Workers Unite)

For the past 100 years, US labor law has left many workers out of unions altogether. Contractors, who now make up 20 percent of the American labor force, typically can’t join. That has led to a long history of workers finding different paths to organizing. The number of worker centers—where laborers can learn about their rights, meet one another, and obtain legal services—ballooned in the 1990s and early 2000s. There are also dozens of alliances that aren’t unions but fight for workers’ rights in similar ways. The National Domestic Workers Alliance has won wage increases and helped enact legal protections for domestic laborers. The Coalition of Immokalee Workers has organized tomato farm laborers into a hunger strike, eventually winning wage increases across the industry.

For now, TWU is a little more anarchic. There’s no nonprofit status, no outside donors, just rank-and-file Target workers organizing themselves, largely through the Internet.

Ryan concluded this was the best tack after trying and failing to unionize workplaces in Richmond. In 2017, just as Donald Trump was taking office, Ryan moved in with his parents, Republicans with a love for Fox News and the Christian Broadcasting Network. He set up his basement as a communist haven and got to work.

He applied for a job at the local Target. He needed the money, but he also saw it as an opportunity to salt— become an employee with the goal of organizing the workplace. He works about 20 to 25 hours a week and makes around $12,000 a year.

Ryan drives the few miles from his parents’ home to the suburban strip where Target is the centerpiece of a shopping center that’s reminiscent of thousands of others. This one also has a Home Depot, Petco, and Chick-fil-A.

Shortly after getting the job, Ryan began agitating. His colleagues had complained about a manager who sexually harassed his employees. Ryan and a few other workers gathered testimonials and planned a ministrike. Ryan stood outside the store with a small group of supporters. Local unions arrived to show solidarity, and the media covered the demonstration. A few weeks later, he got news that the manager no longer worked at the store. It became a blueprint for organizing against Target: Magnify the gap between what the company preaches and how it acts.

“They’re so focused on their public image, and the amount of attention we’re able to get on it was enough to force them to concede to our demand,” Ryan said.

For that reason, he said, he isn’t too worried about retaliation. In fact, the more public he is, the better; privately complaining about a store isn’t considered protected concerted activity by the National Labor Relations Board, but organizing out in the open is.

Note: The 1983–99 private and public sector membership estimates exclude agricultural workers. (Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics)

Get unlimited access: $9.50 for six months.

The stats on labor organizing are grim. Just over 10 percent of the country’s workforce is in a union—a 50 percent decrease since the ’80s. In retail, only 5 percent of workers are organized. The reasons should be familiar to most Nation readers: union busting, right-to-work laws, and labor unions hobbled financially to the point that they cannot effectively organize outside their remaining strongholds.

The legal structure of unionization in the US also shares much of the blame. There are so many loopholes in worker protection laws that it’s relatively easy for employers to get away with firing people for organizing. During the Covid-19 pandemic, employers like Amazon have cited vague employee policy violations to get away with what is clearly union busting.

Kate Andrias, a law professor at the University of Michigan, told me that for several decades the Supreme Court and the National Labor Relations Board under Trump have consistently interpreted laws in favor of corporations. “I don’t think it’s the case that it’s impossible for workers to engage in successful concerted action in a hostile legal regime,” she said. “But it certainly doesn’t help that the laws frequently fail to effectively protect collective action.”

But to Ryan and others, there’s another problem: Many Americans simply do not want to join unions. Recent labor campaigns have failed by large margins. In 2018 the UFCW attempted to organize a Target on Long Island in New York. Nearly four out of five employees voted against it. Last year employees at a Volkswagen plant in Tennessee rejected unionization for the second time. Organization United for Respect at Walmart, a unionization campaign funded in part by the UFCW, also couldn’t draw enough support to make a dent in the company’s million-strong workforce.

“There’s a whole generation or two of mistrust or suspicion or at least resignation that these unions will not be able to do anything for them,” said Dan Graff, the director of the Higgins Labor Program at the University of Notre Dame. “It’s kind of a vicious cycle. The labor movement gets smaller. Unions then look less able to do anything. And it’s hard to escape that.”

Most people in the labor movement are loath to criticize unions. But a big part of Ryan’s pitch is that skeptical workers are right: Unions haven’t been doing enough. Decades ago, most of them abandoned radical acts and strikes in favor of contract negotiations. He points to a UPS contract negotiation in 2018, during which workers voted against the contract but the union ratified it anyway.

“They don’t organize workers to develop their capacity to be leaders,” he said. “It’s up to the paid staff and the internationals to determine all that for them. We’re not a formal union, and we’re not really seeking that at this point…. We got the right to organize. We got the right to strike. What more do we need to do what we want to do?”

At the same time, corporations have gotten better at persuading their employees to remain nonunionized, and Target is among the best. Instead of firing organizers—as Amazon appears to be doing—the company has become expert at doing just enough to placate workers. When the Fight for $15 campaign to raise the minimum hourly wage was gaining traction a few years ago, Target was one of the first big corporations to announce a gradual increase in pay, garnering praise from many outside the company. But then to offset the higher rate, Target began cutting hours and health benefits, which received much less attention than the increase. Ryan and other Target employees see this strategy on a micro level, too. If employees complain about anything, Target encourages them to work out the issues through management or call the employee hot line. (Target did not respond to requests for an interview.)

“Many workers get taken in by this,” at Target and other companies, said Gordon Lafer, a professor at the University of Oregon’s Labor Education and Research Center. “They’re scared to be activists, because they’re scared to lose their jobs, so they hold off on collective action while giving the boss a chance. This can go on for a long time and suck the momentum out of collective action.”

But many labor experts think this is changing. Over the past few years, dozens of worker groups have gone on strike without the backing of unions—teachers in West Virginia, gig laborers for Uber and Lyft, graduate students at the University of California at Santa Cruz. And Americans are increasingly sympathetic to labor. After bottoming out in 2009, support for unions has risen. Last year nearly two-thirds of Americans surveyed by Gallup said they had a favorable view of unions—one of the highest levels of approval in 50 years. Simply put, workers are fed up and taking action.

Sharon Keel is one of those workers. She has worked at Targets in three states for a total of 13 years and currently works in Christiansburg with Ryan. When she started, she found she had little to complain about but little to be enthusiastic about.

Her hours were OK, and she had health insurance. Management never applauded her work, but she could make ends meet. Then Target cut her hours, making her ineligible for health insurance. She hadn’t gone to a doctor for five years, until March of this year, when she turned 65 and Medicare kicked in. Then something seemingly insignificant made Keel reconsider her relationship with the company. A few years ago, as she marked a decade with the company, she heard that it gave employees a $50 Target gift card for 10 years of employment. It didn’t give one to her because her years had been officially reset to zero because of a short employment gap between stores.

Things have gotten worse since then. This year Keel’s father died, and she couldn’t afford to attend his funeral in Alabama. Target used to give employees paid time off for funerals and a sympathy card. It does neither now, she said. The gift card, the sympathy card—they’re small gestures, but they convinced her that the company she’d worked so hard for did not care about her. “You’re just a number,” she said.

She began attending TWU meetings. She told me she now tries to persuade her fellow employees to join, too.

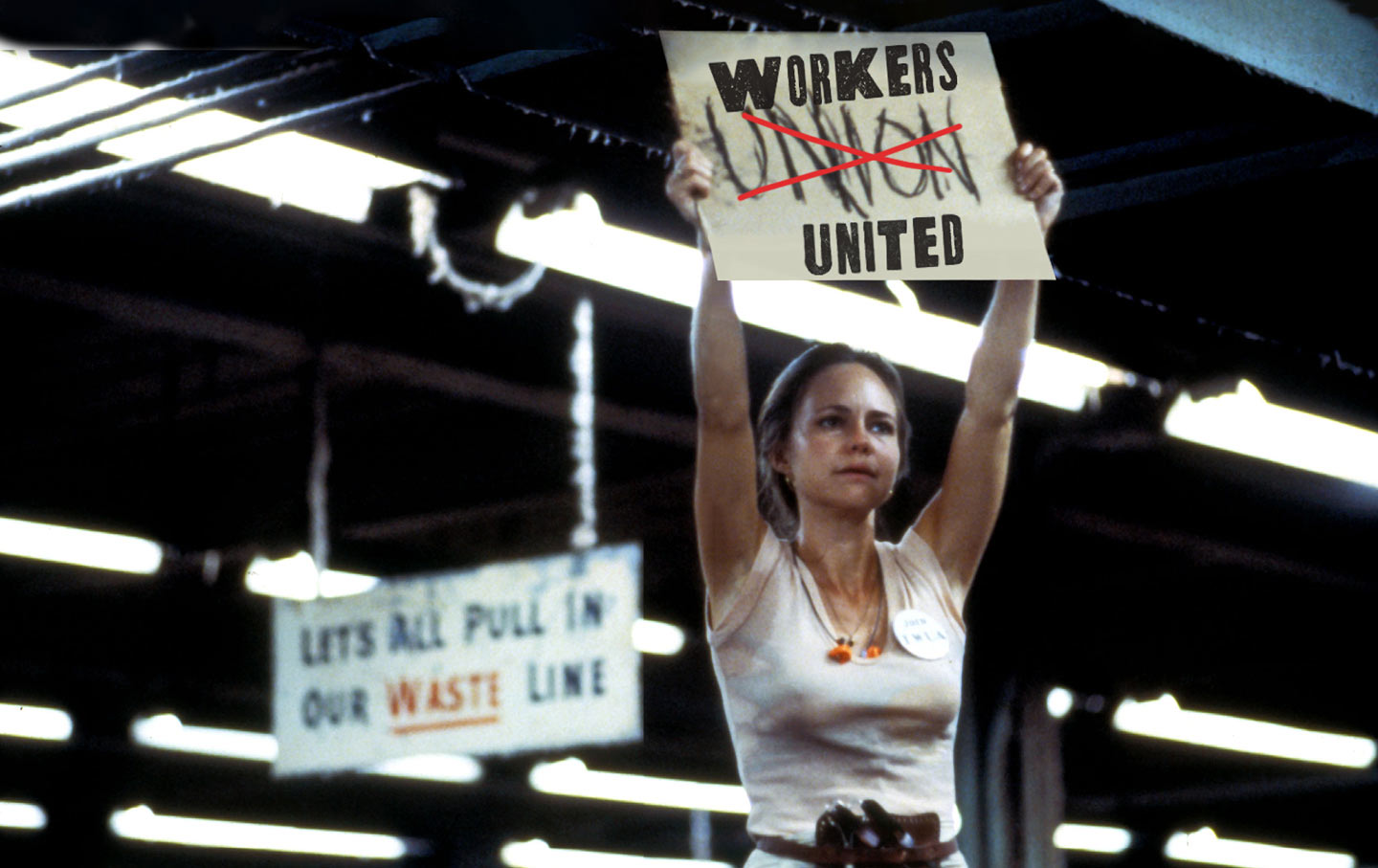

“I grew up [in Detroit] seeing the AFL-CIO, and I just thought that was the best thing ever,” she said. She idolized Norma Rae, the union agitator played by Sally Field in the eponymous 1979 film. “Because, I mean, that was how I felt, that that would be me.”

Ryan bought Keel a poster of the movie. It hangs on a wall in her trailer on the outskirts of town.

Art for change: A drawing by a TWU member advertising a sick-out for hazard pay and improved personal protective equipment.(Courtesy of Target Workers Unite)

Fear is a motivator. The fear of retaliation hasn’t lessened, but the fear of everything else has grown—and that’s an opportunity for organizers. Ryan and countless others have seized the opening provided by the coronavirus crisis to galvanize workers. He answers questions and posts information for Target workers on TWU’s private Facebook page nearly every day. There, workers have detailed how Target hasn’t provided adequate protective equipment, how customers appear not to care about how close they get to employees, and how staffers dread going into work each day. They don’t have much of a choice. Target won’t pay for time off for employees unless they provide a doctor’s note that says they were required to be quarantined or they get a positive coronavirus test result, forcing workers to choose between missing pay if they exhibit any symptoms and getting others sick.

“It’s stressful,” one worker said. “If I get sick, I can’t go home.” Another said he felt a constant low-grade panic working there during the pandemic. “We can be sick. Some could die. But we all need to eat and pay bills.”

Each week, Ryan has been leading video meetings, teaching Target workers their basic labor rights and encouraging them to organize in public and with TWU.

Workers from other companies are also beginning to organize with TWU, including at Shipt, a business that delivers goods from Target and elsewhere that, like the rest of the gig economy, relies on independent contractors. Willy Solis, a Shipt delivery person, said organizing gig workers is hard because they are by design dispersed and much of what they say to one another can be surveilled by the company. Nonetheless, thousands of Shipt workers have reached out to Solis wanting to organize since the Covid-19 crisis started.

Despite the rapid growth of TWU, it’s still tiny—a few hundred members in a corporation that employs 368,000 people. But Ryan draws inspiration from the largely successful wildcat teachers’ strikes in 2018, not only because they were started by workers without the blessing of their union and snowballed into a national movement but also because he sees them as a necessary escalation. When I spoke with him in March, he predicted that more militant actions were not far off. Sure enough, two months later, the country erupted over a series of police killings.

“The pandemic is the straw that broke the camel’s back,” he said.

Andrias said this new wave of labor action is likely to continue. “I think we’re in a moment of crisis where workers are organizing despite all the obstacles,” she said.

Little legacy of labor organizing exists in America’s corporate sprawl. But taking what he has—books and research, online organizing, and most important, the increasing anger of the working class—Ryan believes he can help create something lasting, an ever-growing group of self-trained organizers devoted to building labor power.

From his basement bedroom, Ryan thought back to what helped get him into organizing: Occupy Wall Street. That, he said, reminded Americans that class still existed and that the working class needed to fight. Since then, he’s seen Black Lives Matter, the Bernie Sanders campaign, wildcat strikes across the country, and the ongoing uprisings against law enforcement. In Ryan’s eyes, it’s only a matter of time before all of these movements coalesce into something larger, perhaps a general strike, something TWU wants to be ready to help organize.

“Workers are organizing and resisting, but it’s still very underdeveloped, and it’s still very weak, and especially in places like where I’m at…we’re having to rebuild all that from scratch,” Ryan said. “But there’s definitely a moment, and there’s definitely going to be something that shifts beyond it. It isn’t just going to stay like this forever. I don’t think we’re going back to an old normal. That’s done.”

P.E. MoskowitzP.E. Moskowitz runs Mental Hellth, a newsletter about capitalism and psychology, and is the author of the forthcoming Rabbit Hole, a reported memoir on drugs and American life.