The Supreme Court Is Not Going to Save Us From Donald Trump

The justices have made clear that they do not think the 14th Amendment disqualifies Trump from running for office. That means there’s only one way to stop him—at the ballot box.

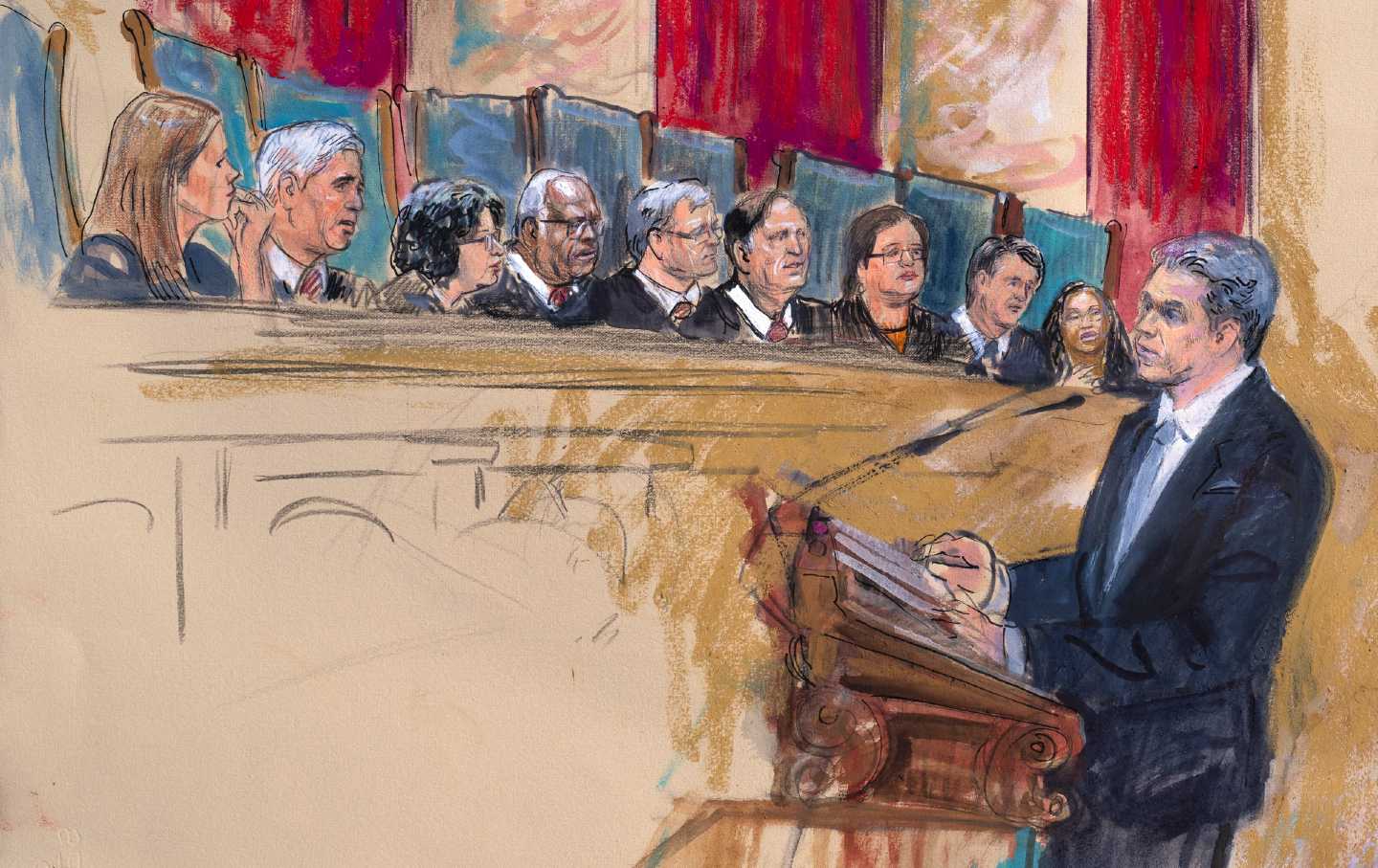

Artist sketch depicting attorney Jonathan Mitchell arguing before the Supreme Court on behalf of former president Donald Trump on Thursday, February 8, 2024, in Washington, D.C.

(Dana Verkouteren via AP)The Supreme Court heard oral arguments yesterday in Trump v. Anderson, the case about whether Donald Trump can be kicked off the presidential primary ballot in the state of Colorado, in accordance with Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, based on his attempt to overturn the 2020 election. To cut to the chase, the court will almost certainly overrule the Colorado Supreme Court and reinstate Trump on the ballot. And it will likely do it on the strength of a unanimous, 9-0 ruling, with all the justices joining together to shout “prank caller” at the 14th Amendment and its clear calls to exclude insurrectionists from office.

That the six conservative justices would come to this conclusion, text be damned, was largely expected. And I anticipated that Chief Justice John Roberts would work hard to craft an opinion that brought the liberal justices on board, so that his eventual ruling wouldn’t seem so drastically partisan. But the upshot of yesterday’s arguments is that Roberts will not need to convince them: At least two of the liberals seemed as eager to keep Trump in the running as any guy sitting in a diner wearing a MAGA hat.

The arguments opened with Jonathan Mitchell, representing the Trump position, giving a master class on how not to argue in front of the Supreme Court. Mitchell, whom readers might remember as the former Texas solicitor general and the architect of Texas’s SB 8 anti-abortion bill, spent an incredible amount of time arguing against himself. The justices literally brought up arguments that they wanted him to make, to help him win the case, and he responded by telling them that they were wrong, or that he didn’t want to make the point because he didn’t think it would help him. (As an example, Mitchell almost refused to argue that Trump was denied due process in the Colorado proceeding, even though there were justices interested in that point). If Trump were, you know, skilled enough to follow along with a Supreme Court oral argument, he might be menacing ketchup bottles over this quality of representation.

Still, it was only when Jason Murray, the lawyer representing the effort to keep Trump off the ballot, rose to argue that the justices really started tipping their hands. Roberts, along with justices Samuel Alito, alleged attempted rapist Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett, all asked Murray why one state—Colorado—should be allowed to decide who gets to be on the ballot for, essentially, the rest of the country.

Murray had a credible answer for this, one that usually wins in conservative circles: states’ rights. Murray said that Colorado had the right to determine its own election rules, and the Constitution grants “near-plenary” power for the states to determine their own election processes for federal officials. This is a point conservatives make constantly when they’re defending the right of states to, say, institute voter ID laws, close off early voting, or make any number of rules that restrict voting rights and limit voting access to poor people or people of color.

But here, states’ rights didn’t satisfy the conservatives, and didn’t persuade Justice Elena Kagan, who had the exact same concerns as the conservatives did. She worried about the lack of “uniformity” that would happen if the court upheld the Colorado ruling. She (like Roberts and Alito) kept hammering on hypotheticals, in which one state would exclude Trump while other states would exclude “other” candidates, and we’d be left in a situation where each state would have entirely different ballots for the presidential election.

Murray, again, had a basically credible answer to this. He said that we had to trust states to apply their own laws faithfully. He pointed out that insurrection was pretty rare and it was unlikely that states would cynically use the standard for political means. Now, I think we all know that Murray’s hopes and dreams are flatly wrong, given that we’ve all seen what red-state governors like Greg Abbott and Ron DeSantis are capable of. But as a legal proposition, the court shouldn’t be deciding cases based on what it thinks bad-faith politicians will do with its decisions. At the very least, if bad-faith political maneuvers are a thing the court now cares about, it might try applying that standard to its voting rights and gerrymandering decisions first, instead of only suddenly becoming concerned about this when an insurrectionist runs for president.

Kagan wasn’t buying Murray’s wishcasting though, and neither was Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. Jackson echoed all of Kagan’s concerns, but added one other: that the president is not an “officer” as defined by the 14th Amendment. I was, frankly, shocked when Jackson started to push this point. The “not an officer” argument is ridiculous. It’s an idea that the Colorado trial court latched onto (the trial court found Trump to be an insurrectionist, but kept him on the ballot; the Colorado State Supreme Court overruled that and barred Trump from seeking office) to avoid kicking Trump off the ballot, and something that conservatives have since bandied about as a potential way out for the court. Jackson has already established herself as the most “textualist” justice on the liberal side of the bench, the one most eager to go toe-to-toe with Neil Gorsuch into the trenches of the Oxford English Dictionary and the original meaning of the Magna Carta. But she generally avoids playing pedantic word games as if the entire Constitution were a New York Times crossword puzzle waiting to be solved. Unlike Gorsuch, she never misses the forest for the trees.

But she did yesterday. She dug into the fact that the 14th Amendment doesn’t specify that it applies to “the presidency” the way it does other “offices” that insurrectionists cannot hold, and then seemed eager to invent a number of reasons for why that is so. I’ve read the same briefs she has, and it would seem she was unpersuaded by the overwhelming historical evidence that the writers of the 14th Amendment obviously did not think that a president who engaged in insurrection could ever run for president again. Instead, she argued that the authors of the amendment were primarily concerned with preventing voters in the South from returning Confederates to office through local or state elections, and somehow just didn’t care if they voted for a former rebel to be president of the entire nation.

I can only assume that the The Wall Street Journal and National Review will soon write op-eds praising Jackson for her intellectual consistency in the face of partisan pressure. I think the best way to understand Kagan’s and Jackson’s political calculations in this case is to realize that they’re far more worried about closely contested states kicking Joe Biden off the ballot than they are about solidly blue states kicking Trump off.

Only Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the most senior liberal, seemed to maintain her skepticism about Trump’s argument throughout the hearing. But even she sounded resigned to the inevitable. Her questions meandered a bit and lacked the righteous punch she usually brings to the bench. She did not sound like a person gearing up to be the lone holdout in an 8-1 case; she did not sound like someone preparing for a blistering dissent. Instead, she sounded almost like she was playing for an important footnote in a unanimous opinion.

The lack of liberal dissenters was the most disappointing thing to me about the hearings. That’s because I believe Roberts will be highly motivated to find a 9-0 solution to this case. If the liberals had put up more of a fight, it might have gotten Roberts to trade something in order to get them on board—not in this case, but on some of the other huge Trump-adjacent decisions the court will have to deal with. Perhaps 9-0 here but an agreement to not grant a stay in the Trump immunity case could have been scored. Perhaps an agreement to hold the January 6 insurrectionists accountable for obstruction of Congress. Something. The justices say that this kind of horse-trading doesn’t happen, that they take every case on its own merits, but I straight-up do not believe them. I think trading and deals and wink-nod agreements happen all the time, and I think this was an opportunity for the liberals to extract something for their votes. An opportunity the liberals gave up in their eagerness to stop Texas from banishing Joe Biden from the presidential ballot or whatever other Republican bogeyman they think is hiding under their beds.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →I’ve said repeatedly that there is no way in hell the Supreme Court would allow the likely Republican nominee to be stricken from the ballot. I’ve said repeatedly that courts and judges simply do not have the strength and courage to end Trump’s presidential campaign as a matter of law. I’ve said repeatedly that the only way to be rid of him is to defeat him at the ballot box, again, and beat back his forces who will try to steal the election, again.

Those warnings still hold after the court’s oral arguments. Once again, the law is not coming to save us. According to the Supreme Court, “states’ rights” exist only to make it harder for people to vote, not harder for insurrectionists to rule.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Shocking Confessions of Susie Wiles The Shocking Confessions of Susie Wiles

Trump’s chief of staff admits he’s lying about Venezuela—and a lot of other things.

The King of Deportations The King of Deportations

ICE’s illegal tactics and extreme force put immigrants in danger.

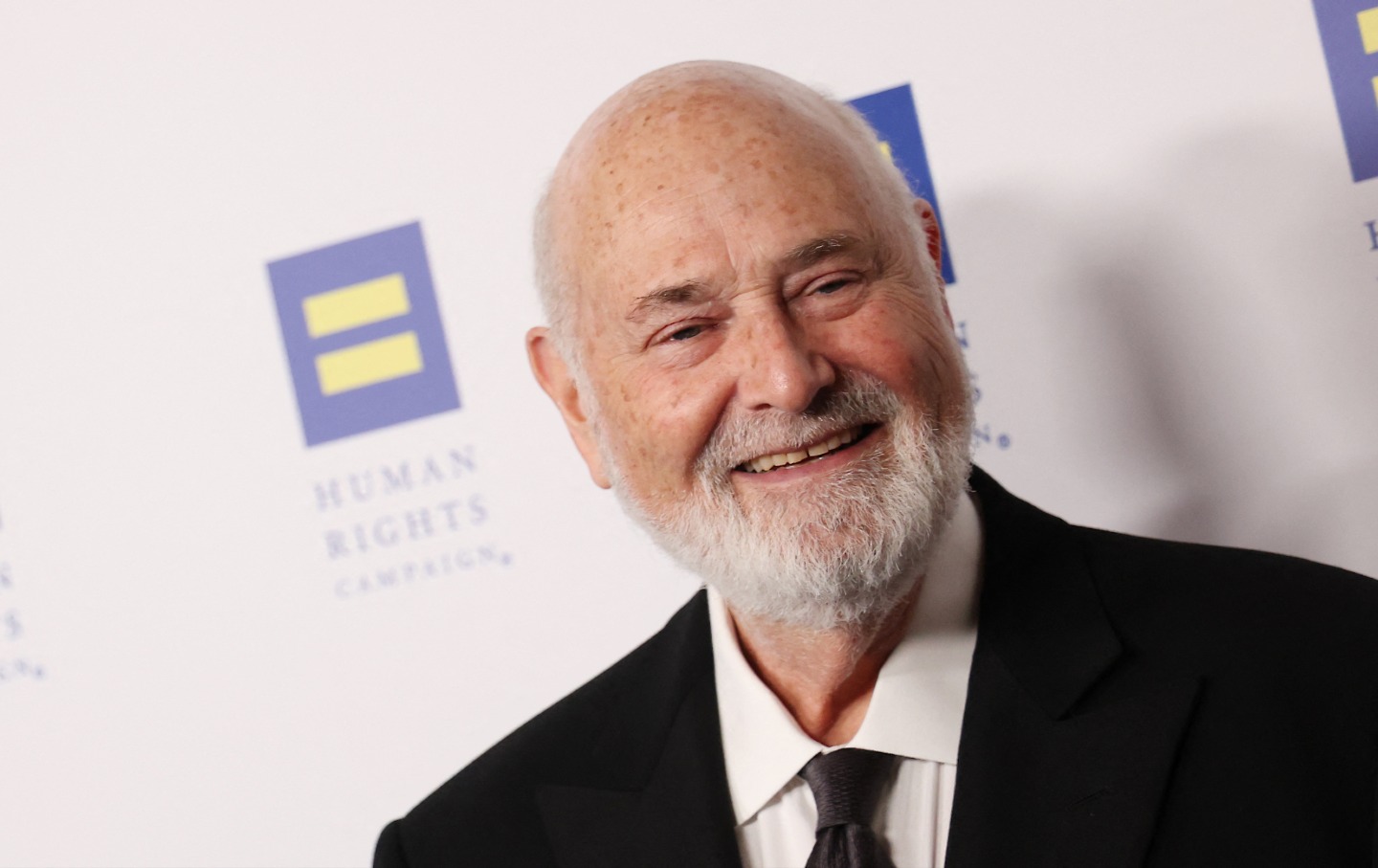

How Rob Reiner Tipped the Balance Against Donald Trump How Rob Reiner Tipped the Balance Against Donald Trump

Trump’s crude disdain for the slain filmmaker was undoubtedly rooted in the fact that Reiner so ably used his talents to help dethrone him in 2020.

The Economy Is Flatlining—and So Is Trump The Economy Is Flatlining—and So Is Trump

The president’s usual tricks are no match for a weakening jobs market and persistent inflation.

Trump’s Vile Rob Reiner Comments Show How Much He Has Debased His Office Trump’s Vile Rob Reiner Comments Show How Much He Has Debased His Office

Every day, Trump is saying and doing things that would get most elementary school children suspended.