Trump Gets Closer to Trial in Georgia

Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis has already induced four of Trump’s codefendants to serve as prosecution witnesses.

Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis speaks at a news conference in the Fulton County Government building on Wednesday, August 14, 2023, in Atlanta, Ga.

(Joshua Lott / The Washington Post via Getty Images)One sure measure of the legal woes assailing former president Donald Trump is his plan to dismantle the independence of the federal justice system if he again wins the presidency. A sobering dispatch from The New York Times lays out the scale of the projected ideological takeover, relying on interviews with seven Trump insiders involved in its planning as well as Trump-aligned lawyers, past and present. The agenda is clearly to subordinate the federal law enforcement complex, like the civil service and other arms of government afflicted with insufficient MAGA fealty, to the full and capricious authority of the crime lord president.

Times reporters Charlie Savage, Maggie Haberman, and Jonathan Swan trace the origins of this crusade to Trump’s own Justice Department’s resistance to key executive directives, such as refusing to prosecute nonexistent cases of election fraud arising from the 2020 presidential balloting. But that’s clearly just half the picture here: MAGA Nation remains stolidly convinced that the Biden Justice Department has been “weaponized” to engineer bogus prosecutions of its maximum leader at the behest of Attorney General Merrick Garland and special prosecutor Jack Smith. Meanwhile, the Fulton County Trump prosecution led by Fani Willis and the New York civil fraud action against Trump’s business empire brought by state Attorney General Letitia James drive home the same basic message to the Trump faithful: A justice system loosed from top-down MAGA control will set out to punish MAGA crimes. Cue the histrionic Jim Jordan hearings, the conspiracy headlines, and the Truth Social tantrums.

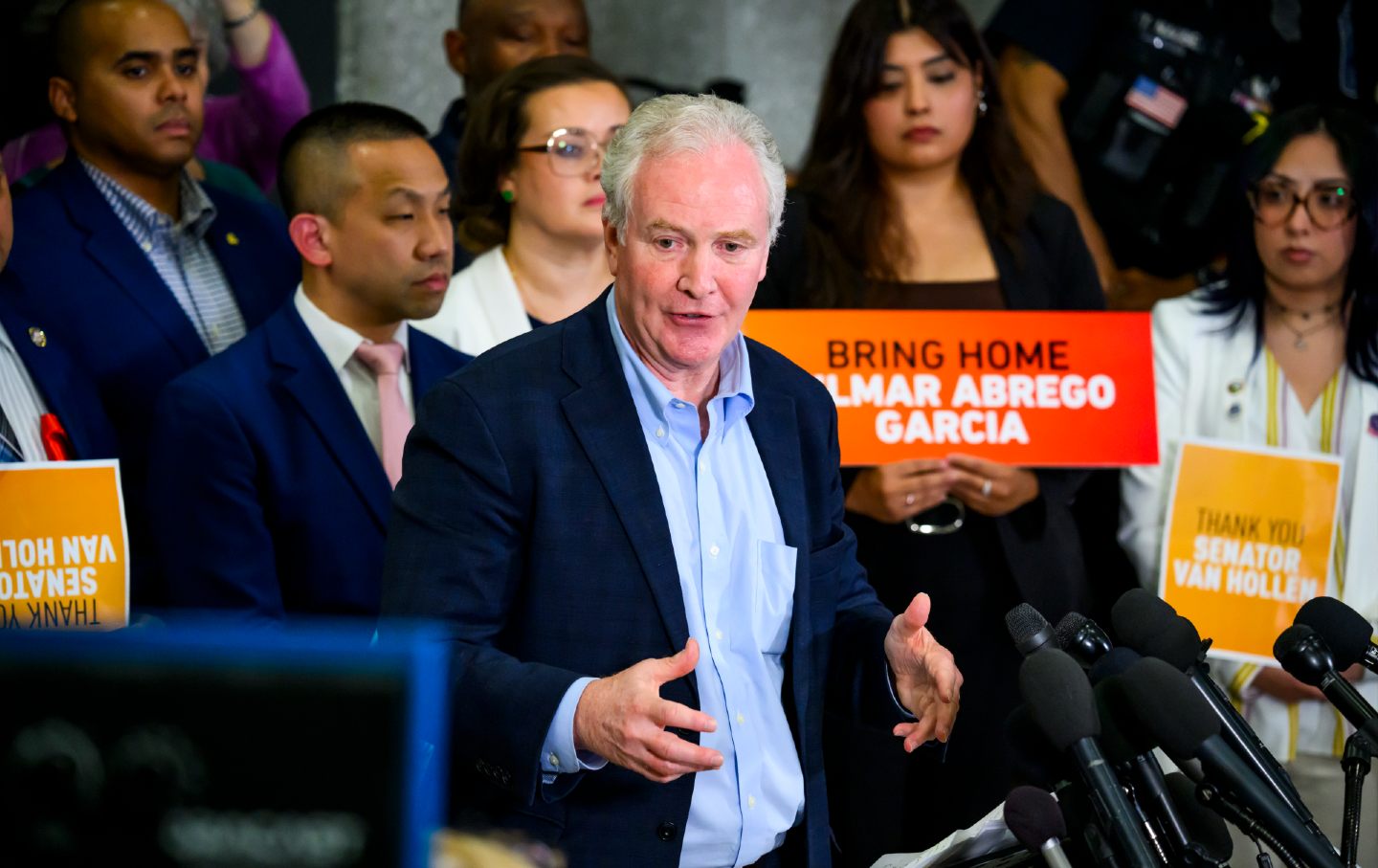

Amid all the whining and fury, it’s easy to lose track of the actual progress of the many Trump-centric legal proceedings under way. But the main takeaway is that things aren’t looking very rosy for the defendant. The courtroom reckoning for the Trump Organization in New York has soaked up the most media attention, largely because Trump’s children have been subpoenaed to testify, and showcased comically implausible levels of professional amnesia. Jack Smith’s federal court case against Trump for his role in fomenting the failed coup of January 6 has also drawn a fair amount of commentary—notably from the defendant himself—most recently around Judge Tanya Chutkan’s reinstatement of a gag order on Trump. But Fani Willis’s prosecution in Georgia is making significant inroads in the less flashy realm of lining up actual evidence and witnesses to present in court.

The Fulton County case largely rests on a pretty flagrant smoking gun: Trump’s infamous phone call to Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger demanding that the election official “find” 11,000 votes to reverse its migration into the Biden column—or else face painful legal and political consequences. More than that, though, Willis lodged a racketeering complaint to bring in a wide array of 18 codefendants along with Trump—and per the strong-arm logic of such proceedings, she’s already induced four of them to serve as prosecution witnesses. Three of these defendants were Trump attorneys tasked with overseeing his efforts to overturn Biden’s legitimate election win; meanwhile, CNN reports, Willis’s office is in discussions seeking to strike similar deals with at least six other defendants. Willis has also indicted former Trump chief of staff Mark Meadows, and secured his testimony before the Fulton County grand jury.

What specific evidence emerges from this rolling inquiry remains to be seen—Willis’s trial won’t begin until next summer, at the earliest. The three attorneys who’ve flipped so far—Sidney Powell, Kenneth Chesebro, and Jenna Ellis—might be able to limit their testimony by asserting attorney-client privilege. (Though Trump has already complicated that prospect in Powell’s case by denying that he ever really retained her as his attorney.) Their role in proving a conspiracy with Trump at the center may also be limited. “The lawyers who pled in Georgia didn’t plead to the main conspiracy count,” says former federal prosecutor Ankush Khardori. “And they don’t appear to have pled to any part of the case where Trump was closely involved as a factual matter—Powell, for instance, appears to have pled guilty on the basis of her involvement in an incursion into Georgia’s election systems. And, of course, no one’s spending any time in prison.”

Still, there’s no question that all three were central players in the legal effort to overturn the election, and that the prospect of criminal prosecution, and the reputational damage that comes with it, has concentrated their minds on cooperative disclosure. “In cases like this, the playbook is always defined by the evidence, and a prosecutor’s ability to use that evidence in a way that’s effective to the people that they need to plea,” says Paul Pelletier, another former Justice Department prosecutor who specialized in white-collar crime. “Her playbook’s been great for this kind of case—the pleas haven’t been draconian for these lawyers, but getting a lawyer to plead guilty is not easy.”

The pleas in Georgia have touched off a good deal of speculation over how and whether the testimony there can be bootstrapped into Smith’s related federal prosecution of the January 6 case before D.C. District Judge Chutkan. Chardori cautions that it may not be the cross-jurisdictional breakthrough that it might seem at first blush. “These people all had significant reasons to cooperate with Smith’s probe independent of the Georgia case—i.e., so that they don’t end up on the wrong side of federal prosecutors,” he says. “Powell, of course, is already an uncharged coconspirator, so her incentives to cooperate with Smith were already significant even before the Georgia case came.”

Chesebro is also thought to be one of the unindicted coconspirators in Smith’s case; for him, Powell, and anyone else in that category, it’s largely a question of ensuring that cooperating in Georgia won’t further expose them to liability in D.C. “They’re in a trick bag, because I always thought Smith intended to get them at some point,” Pelletier says. “You’re putting a target on their back, giving them some incentive to work out a deal. The problem is that in the state case, they have a system where the felony goes away so these lawyers can practice law again at some point. In the federal system, there’s nothing like that. If Smith gets hold of those statements and subpoenas them to trial, they can take the Fifth, but the statements they made in Georgia can still be used against them.”

In any event, the lawyers’ testimony may be outweighed by the evidence furnished by Meadows, a key figure at the center of the demented intrigue surrounding the January 6 insurrection, as the recently published revelations of his former aide Cassidy Hutchinson has made clear. (She has, among other things, reported that her boss’s suit smelled of “burning paper” in the final days of the Trump administration.) Willis’s indictment of Meadows is “the wild card,” Pelletier says—particularly in view of his past stonewalling of the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the US Capitol. Meadows has now apparently put in three appearances before Willis’s grand jury. “That means he’s being quote cooperative, unquote,” Pelletier says. “If that’s true, he’s probably got an adjustable immunity deal with a letter from the prosecution, meaning that they obviously believe he’s telling the truth.”

But Meadows faces something akin to the photographic negative of the legal quandary confronting the Trump lawyers: He’s a named coconspirator in Smith’s case, and he has to tread carefully to avoid his testimony there playing havoc with what he’s telling the prosecutors in Fulton County. That’s one key reason Meadows had unsuccessfully sought to get his charges in Georgia transferred into federal court. “The trick for him is that he would testify in the Chutkan case in D.C., and that testimony will be public,” Pelletier says. “Willis can use that testimony against him. And that trial will go before her trial…. So before he testifies in that trial, Smith will probably work a deal with Willis’ team where he gets first offender status, and it’ll all go away if he serves probation. If he makes those statements and they’re admitted against him in Georgia, that makes it more likely he’ll get convicted.”

Of course, none of this maneuvering will prove greatly consequential should Trump regain the presidency next November and use his authority to extricate himself from whatever legal jeopardy he’s facing then, as a sort of prelude to the broader Caesarean makeover of the federal justice system. “If the D.C. case actually goes to trial and Trump is convicted before the election, that will presumably be meaningful as a historical matter, hopefully, even though Trump will likely be able to kill the case once he’s in office,” Khardori says. “If Trump pardons himself, for instance, there may be people claiming that the pardon is unconstitutional and that the case can be resurrected against him after he leaves office. Needless to say, these would be totally untested waters, though I find it hard to believe that this would work as a practical matter.”

That’s a sobering prospect, to put it mildly—but it’s also a reminder that Trump’s nonstop raging at his various court reckonings as glorified “election interference” is ultimately rooted in the panic of the flagrantly guilty. “His ass is in a sling, and he knows it,” Pelletier says.

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation